Introduction

$ (document).ready(function() { SampleGalleryV2({“containerId”:”embeddedSampleGallery_2419057207″,”galleryId”:”2419057207″,”isEmbeddedWidget”:true,”selectedImageIndex”:0,”isMobile”:false}) });

The Canon EOS Rebel T8i (also known as the EOS 850D or Kiss X10i in some markets) is a 24MP DSLR camera that is compatible with the company’s EF and EF-S mount lenses. It has an optical viewfinder, but it also has a usable and responsive touchscreen interface and live view experience that’s a match for the company’s mirrorless camera options.

Jump to:

What’s new | Body, handling| Image quality | Autofocus | Video | Conclusion | Samples

For much of the world, shifting consumer preferences towards mirrorless cameras have left DSLRs looking like relics of history, though Europe and the Americas remain holdouts. Last year, Europeans still bought about 1.4 DSLRs for every mirrorless camera sold, while in the Americas the ratio was even higher at 1.7:1.

So why might you consider a DSLR in our increasingly mirrorless world? Some photographers still prefer DSLRs for their crisp, lag-free through-the-lens viewfinders, and there’s a much wider array of lenses available to DSLR shooters without the need for adapters.

|

| ISO 2500 | 1/100 sec | F5 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 44mm |

Yet relatively few manufacturers are left in the consumer DSLR market. Only Canon, Nikon and Ricoh (which makes Pentax-branded DSLRs) remain, making new models few and far between. Among these, Canon’s EOS Rebel series are the biggest sellers. The Rebel T8i now sits at the top of that line, replacing 2017’s T7i.

Priced at $ 749.99 body-only or $ 900 with an EF-S 18-55mm IS STM kit lens, the Canon T8i is available immediately.

Key specifications

- 24-megapixel APS-C image sensor

- EF or EF-S lens compatibility

- ISO 100 to 25,600, extends to 51,200

- 7 fps continuous shooting, or 7.5 fps in live view

- 45 point, all cross-type phase-detect AF

- 0.51x pentamirror viewfinder with 95% coverage

- 3.0″ vari-angle touch-screen LCD

- 24p 4K video with 1.6x crop, or full-sensor 1080p60

- 800 shot battery life, or 310 shots with live view

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 250 | 1/100 sec | F5.6 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 55mm |

Back to top

What’s new and how it compares

|

| The AF-ON button and rear dial make the T8i a more flexible camera for users to learn and grow with than lesser Rebels. |

Externally, the 24-megapixel Canon T8i looks very similar to its predecessor from most angles, although there are some control tweaks to be found on its rear panel including a new rear control dial and AF-On button. While Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity remain, NFC has been dropped as the constant Bluetooth connection speeds up the connection process the way NFC used to. Lastly, the flash must now be raised manually when needed, as it can no longer pop up by itself. As we’ll see later on, this is a good thing.

On the inside, while the sensor resolution and sensitivity range are unchanged, a faster image processor allows a modest increase in burst performance. It’s now rated at 7 frames per second through the viewfinder, or 7.5 fps in live view mode, up from 6 fps in the T7i. There’s also a somewhat finer-grained 384-zone metering sensor in place of the earlier 315-zone sensor.

|

| The Rebel T8i uses a familiar 24MP sensor with Dual Pixel AF that offers solid noise performance and resolution. |

Canon has also added support for 4K movie capture, although this comes with several limitations including a significant focal length crop, contrast-detection autofocus (rather than the more reliable Dual Pixel AF you get in lesser Full HD modes) and a fixed 24 fps frame rate. And autofocus algorithms have been refined to add eye detection in live view mode, and face detection when shooting through the viewfinder.

How it compares…

Compared with two of its mirrorless rivals, the Nikon Z50 and Sony a6100, the Canon T8i offers much better battery life, so long as you stick to its optical viewfinder. The T8i is quite a bit bulkier though, despite not offering weather-sealing.

| Canon T8i | Nikon Z50 | Sony a6100 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSRP (body) | $ 749.99 | $ 859.95 | $ 750 |

| Sensor | 24.1MP APS-C | 20.9MP APS-C | 24MP APS-C |

| Type | DSLR | Mirrorless | Mirrorless |

| Sensitivity (native) | 100-25600 | 100-51200 | 100-32000 |

| Lens mount | Canon EF / EF-S | Nikon Z | Sony E |

| Viewfinder type | Optical pentamirror SLR | 2.36M-dot OLED EVF | 1.44M-dot EVF |

| Viewfinder magnif. / coverage | 0.51x, 95% | 0.68x, 100% | 0.71x, 100% |

| LCD | 3” fully articulating | 3.2” tilting | 3” tilting |

| Touch-screen | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Included flash | Pop-up | Pop-up | Pop-up |

| Weather-sealing | No | Yes | No |

| Max. burst | 7.0 fps (viewfinder) / 7.5 fps (live view) | 5 fps (mechanical) / 11 fps (electronic) | 11 fps (mechanical) |

| Max. shutter | 1/4000 | 1/4000 | 1/4000 |

| Video | 4K/24p, 1080/24-60p | 4K/24-30p, 1080/ 24-120p | 4K/24-30p, 1080/ 24-120p |

| 4K crop | 1.6x | None | 1.2x (4K/30p) |

| Battery life (CIPA) | 800 shots (OVF); 310 shots (Live View) | 320 shots | 420 shots |

| Dimensions | 131 x 103 x 76mm | 127 x 94 x 60mm | 120 x 67 x 59mm |

| Weight | 515 g | 450 g | 396 g |

One thing that’s hard to capture in a table are the differences between the camera’s AF systems. In its optical viewfinder, the T8i’s 45 autofocus points are centrally clustered, which can get in the way of creative compositions. Switch into live view and you have autofocus points spread across the frame, the same as the other options give you on their rear screens and their electronic viewfinders.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 500 | 1/60 sec | F4 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 18mm |

Compared to the smaller and more affordable Canon Rebel SL3, the T8i offers more sophisticated autofocus through its slightly smaller finder, though the SL3 offers you a third more shots per charge. On the mirrorless side of the equation, the T8i bests the Canon EOS M50 Mark II’s 235-shot battery life whether you’re using the optical viewfinder or live view, but the mirrorless model is lower-priced, significantly more compact / lightweight and offers faster 10 fps burst capture.

Back to top

Body, handling and controls

|

Although its body is plastic, the Canon T8i is very solid in-hand, with no creaks or flexing. It’s also pretty light and compact for a DSLR. The main controls are well-placed and easy to locate by touch.

The new AF-On button is ideally situated for quick autofocus adjustments with a slight thumb motion. (And via a custom setting, can be set to AF-Off instead.) The Wi-Fi button and indicator lamp are gone but won’t be missed, as you won’t need them often. We recommend connecting via Bluetooth, which maintains a constant connection that draws little power, and also makes connecting via Wi-Fi to send images a snap.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 100 | 1/125 sec | F5.6 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 55mm |

The new rear control dial is also a nice addition, though since it’s integrated with the four-way controller, it can’t be reached without adjusting your grip. On the plus side, it’s only active when the exposure metering system is brought to life by a half-press of the shutter button or you’re in a menu, preventing accidental settings changes.

|

| There will always be some photographers that prefer an optical viewfinder; the T8i’s is serviceable, but it’s on the small and dim end of the spectrum. |

Sadly, the pentamirror viewfinder is dim and tunnel-like compared with the electronic finders of mirrorless rivals and even some rival SLRs, such as the less-expensive Pentax K-70 (which has a larger pentaprism design which is brighter than pentamirror designs).

The rear LCD is crisp and easy to see even under sunlight if you turn up the brightness. Its fully-articulated mechanism allows framing from most angles, even for selfies.

|

| The vari-angle LCD allows selfie-shooting too, but the ergonomics aren’t ideal when holding the camera backwards. Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 2000 | 1/60 sec | F4 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 18mm |

The on-screen UI is standard Canon. It’s fairly clear and logically laid-out, and can be navigated with buttons, dials or the very precise touchscreen. Your most-used options can be saved in the My Menu section for quick recall.

Battery life is excellent when shooting stills through the viewfinder, and I never needed a second battery even during lengthy day trips. (I passed 500 frames captured without the charge level indicator dropping even a single bar, which impressed me.) If you shoot a lot of video or use live view frequently, the LCD can burn through power fairly quickly, though. For that reason, the T8i goes to sleep by default after ten seconds unless in menus or live view / playback modes.

|

| Top plate controls are fairly typical Canon, and the quick switch over to video mode is a nice touch. |

A standalone charger is included in the bundle, so you can leave a second battery charging while using the camera. Unfortunately in-camera charging via USB isn’t supported, so you can’t share a charger and cable with another device when you want to pack light. As well as USB, there are HDMI, microphone and remote control ports.

Back to top

Image quality

With the same sensor resolution and sensitivity range as its predecessor, you might expect similar image quality from the Canon T8i: and you’d be right. As an affordable camera aimed at entry-level photographers, it’s good enough but won’t win any awards. That’s not to say there are no differences, however.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 800 | 1/80 sec | F4.5 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 24mm |

Out of camera JPEGs mostly showed pleasing color both outdoors and under artificial light, although I found the latter a little more variable, with some images a tad warm and others a little on the cool side. In both the green fully-automatic mode and program autoexposure, the T8i’s metering proved pretty accurate, and at lower sensitivities there was a fair amount of fine detail as well, although I felt the default sharpening was a touch aggressive.

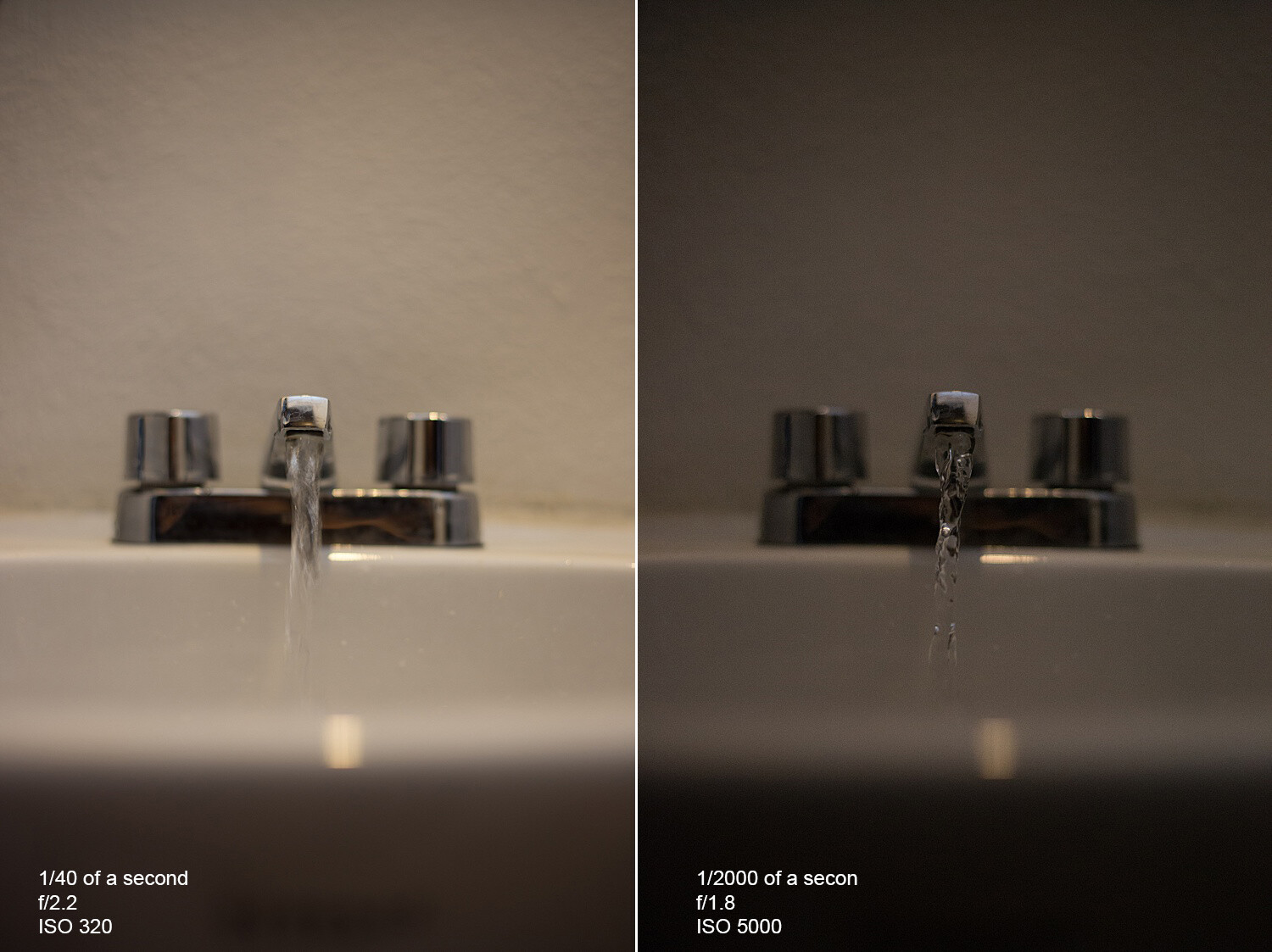

ISO sensitivity in auto mode is limited to a maximum ISO of 6400 by default, and that seems like a good cutoff point. Some noise and loss of saturation starts to become noticeable by ISO 3200, but it’s not until you reach ISO 6400 that it really begins to intrude. You’re best off avoiding ISO 12800 and above as there’s a significant loss of fine detail to noise, and colors can look decidedly washed out.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 3200 | 1/80 sec | F4.5 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 18mm |

Of course, shooting in Raw format helps somewhat as you can rely on the greater processing power of your computer to help tame noise while still holding onto color and detail. And there’s a fair bit of scope to correct exposure within a couple of stops, as well. Raws can also be processed in-camera, which is a nice touch for making quick adjustments on the go.

|

| We’re honestly pleased to find that the T8i’s flash must be manually raised; previous Canon Rebels would often raise their automatically in situations where it actually has a negative impact on your images. |

One notable change is that the Rebel T8i no longer tends to overexpose nearby subjects by raising and firing the flash when it’s not really needed, since it can no longer pop up automatically. You need to pay attention to your shutter speeds, though, and either raise the ISO, or lift the flash yourself. Sadly, there’s no warning in the viewfinder when shutter speeds stray below the point where exposures can safely be shot hand-held.

Back to top

Autofocus

The Canon T8i’s autofocus system has two distinct operating modes, depending upon whether you’re using the optical viewfinder or live view modes. Both systems are capable of locking focus quickly and accurately in good light. In darker conditions, both take a bit longer to achieve a lock, but if I was capable of seeing the subject through the viewfinder, the camera could usually manage to focus on it within a couple of seconds.

|

| A simplified look at the T8i’s optical viewfinder AF system. |

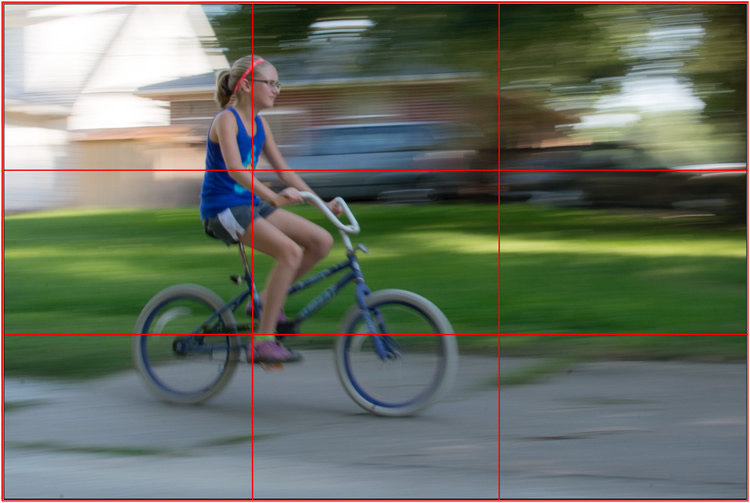

When shooting through the viewfinder there are a total of 45 autofocus points, all of which are cross-type. As you can see in the above illustration, they only cover about two thirds of the frame width and a little over a third of the frame height. For live view mode, almost the entire frame is covered vertically, and significantly more of its width as well.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 500 | 1/60 sec | F4 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 18mm |

Live view also offers both face and eye detection and lets you select which face or eye to focus on using the four-way controller or touch-screen. Viewfinder shooting only has face detection, and you can’t directly control which face to focus on, although if you aim directly at a particular face before half-pressing the shutter button, the camera will then try to follow that face.

Both systems detect faces pretty well, and the tracking implementation is fairly robust. In testing with my son running and riding a bike directly towards me, the T8i was able to accurately track his location and keep the focus locked on his face most of the time until he was very close to the camera. This isn’t by any means a sports shooter, but I think it’s more than capable of keeping up with amateur photographers’ needs in this respect.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 100 | 1/60 sec | F7.1 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 27mm |

Really, my only complaint with autofocus is that it can be confusing if you’re frequently switching between live view and viewfinder shooting. Each mode is configured separately, so for example switching one mode to continuous servo AF won’t affect the other mode’s setup. On the other hand, this separation of settings could be useful if you’re switching from shooting stills in the viewfinder and video in live view. Which brings us to…

Back to top

Video

The addition of 4K video is one of the bigger changes in the Canon T8i, but it’s really rather a shame that it comes hobbled by several significant limitations.

First and most importantly, there’s that significant 1.6x focal length crop on top of the crop imposed by its APS-C sensor size. In other words, a 2.6x effective crop even before you enable digital IS, which crops in still further. In 4K mode without digital IS, the optional 18-55mm kit lens yields an effective 47-143mm range, so your wide-angle options are seriously limited.

The longer effective focal length also means that even with both optical and digital IS active, the stabilization system can struggle to smooth camera shake in 4K, especially if you’re walking.

4K mode comes with a fixed 24 frames per second capture rate, too, and uses contrast-detection autofocus which, compared to phase detection, is slower and has slight but noticeable hunting.

The good news is that if you can put up with those limitations, 4K image quality is fairly good, with lots of crisp detail and pleasing color. And while there’s definitely some rolling shutter effect present, causing verticals to lean during subject motion or quick pans, it’s far from the worst I’ve seen.

But I think it’s better to look at this as a Full HD camera which can also shoot 4K with more distant subjects and relatively sedate motion in a pinch. In Full HD, where you get phase detection AF and access to frame rates as high as 60 fps, there’s less fine detail but focusing is quicker and more confident, and motion is rendered more smoothly. The biggest downside is that Full HD seems more prone to moiré and false color artifacts.

The T8i lacks significant scope for slow-motion video, but does offer a time-lapse movie mode, as well as supporting manual exposure, focus peaking and external audio recording.

Back to top

Conclusion

|

At the end of the day, the Canon Rebel T8i leaves me with rather mixed emotions. On the one hand, for fans of DSLRs like myself, there are fewer and fewer choices on offer, and it does pack quite a lot into a fairly compact, lightweight package by DSLR standards.

But on the other hand, it trails its mirrorless camera rivals in terms of both autofocus and burst capture performance. And the feature which differentiates it most clearly from those rivals – that mirror-based optical viewfinder – gives a disappointingly small and dim view of your subject.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 12800 | 1/60 sec | F4 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 18mm |

While 4K video capture is finally available in the Rebel T8i, it also comes with some major limitations that make it feel more as if it was added to fill out the spec sheet than for real-world use.

But with all of that said, the T8i does give you pretty good still image quality and usable high-definition video capture. And it does so at a pretty affordable pricetag, as well, and with battery life that’s in a totally different ballpark to mirrorless rivals if you tend to rely on the viewfinder.

The Rebel T8i isn’t the future for Canon, but it offers plenty of features and good ergonomics at an affordable pricetag.

There’s definitely something to be said for the vast range of Canon EF and EF-S mount lenses on offer, too; though keep in mind there isn’t a ton of variety in the more affordable EF-S range, and the EF lenses, designed for larger full-frame sensors, are bigger and pricier. And with Canon focusing on its new RF mount, we wouldn’t expect a glut of new EF and EF-S lenses to suddenly appear down the line.

|

| Out-of-camera JPEG. ISO 25600 | 1/25 sec | F5.6 | Canon EF-S 18-55mm @ 55mm |

So, does the Canon T8i represent the future for Canon? Probably not. But does it offer plenty of camera for the money, particularly for the less experienced photographers at which it’s aimed? I’d say so, despite my reservations about its viewfinder and 4K video capabilities.

And I think that makes it a worthwhile buy, especially if you happen to spot it for sale below its list price.

| What we like | What we don’t |

|

|

Sample gallery

$ (document).ready(function() { SampleGalleryV2({“containerId”:”embeddedSampleGallery_4631840432″,”galleryId”:”4631840432″,”isEmbeddedWidget”:true,”selectedImageIndex”:0,”isMobile”:false}) });

Scoring

|

Canon EOS Rebel T8i (EOS 850D / EOS Kiss X10i)

Category: Entry Level Interchangeable Lens Camera / DSLR

|

|

Build quality

Ergonomics & handling

Features

Metering & focus accuracy

Image quality (raw)

Image quality (jpeg)

Low light / high ISO performance

Viewfinder / screen rating

Performance

Movie / video mode

Connectivity

Value

|

PoorExcellent

|

||||

|

Conclusion

The Canon EOS Rebel T8i is well-built with comfortable ergonomics and provides solid image quality for users that prefer an optical viewfinder. Unfortunately, its video capabilities aren't that impressive, and the viewfinder autofocus system is a little basic compared to what you get on mirrorless cameras through their electronic finders. Still, if you're in the market for a reasonably affordable DSLR, the EOS Rebel T8i is worth a look.

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

RegularScoreCompareWidget({“mainElementId”:”scoringWidget”,”mainProduct”:”canon_eos850d”,”scoringSchema”:{“id”:”SLRs”,”variables”:[{“id”:”BuildQuality”},{“id”:”ErgonomicsAndHandling”},{“id”:”Features”},{“id”:”MeteringAndFocusAccuracy”},{“id”:”QualityRaw”},{“id”:”QualityJpeg”},{“id”:”LowLightHighISO”},{“id”:”ViewfinderScreenRating”},{“id”:”Optics”},{“id”:”Performance”},{“id”:”Movie”},{“id”:”Connectivity”},{“id”:”Value”}],”categories”:[{“id”:”EntryLevel”,”label”:”Entry Level Interchangeable Lens Camera / DSLR”,”shortLabel”:”Entry Level”},{“id”:”MidRange”,”label”:”Mid Range Interchangeable Lens Camera / DSLR”,”shortLabel”:”Mid Level”},{“id”:”EntryLevelFullFrame”,”label”:”Entry Level Full Frame Camera”,”shortLabel”:”Entry Level Full Frame”},{“id”:”MidRangeFullFrame”,”label”:”Mid Range Full Frame Camera”,”shortLabel”:”Mid Range Full Frame”},{“id”:”SemiProfessional”,”label”:”Semi-professional Interchangeable Lens Camera / DSLR”,”shortLabel”:”Semi-professional”},{“id”:”SemiProfessionalFullFrame”,”label”:”Semi-professional Full Frame Camera”,”shortLabel”:”Semi-professional Full Frame”},{“id”:”Professional”,”label”:” Professional Interchangeable Lens Camera / DSLR”,”shortLabel”:”Professional”},{“id”:”LargeSensorCompactEntry”,”label”:”Entry Level Large Sensor Compact Camera”,”shortLabel”:”Entry Level Large Sensor Compact”},{“id”:”LargeSensorCompactEnthusiast”,”label”:”Enthusiast Large Sensor Compact Camera”,”shortLabel”:”Enthusiast Large Sensor Compact”},{“id”:”VideoCamera”,”label”:”Video Camera”,”shortLabel”:”Video Camera”}]},”helpText”:”Choose one or more cameras from the drop-down menu, then roll your mouse over the names to see how their scores compare to the camera on review.”})

Articles: Digital Photography Review (dpreview.com)

You must be logged in to post a comment.