When going out and photographing you put your heart and soul in to capturing that special moment, and later, you may pay great care and attention to finishing the image off in post-processing. You are so proud of the results you simply cannot wait to share it online, or add to your portfolio on your website!

One of the most popular practices amongst many photographers is the humble watermark; an opaque logo or text layered on top of an image. But is watermarking really necessary to protect your images – and is it really beneficial, or does it just get in the way?

For the benefit, if are unfamiliar with what a watermark is, it is placing a logo or text (or a combination of the two) with a reduced opacity over the main image. So why watermark in the first place?

Don’t know how to make a watermark? Check out: How to Watermarking Images With Photoshop and Lightroom.

What do watermarks do?

Watermarks prevent, or reduce the chance, of your images being stolen or used without your permission.

You’ve worked very hard – from capturing the image to editing it, and the last thing you want is for somebody to use your image without your permission; especially if it’s for the their financial gain. You would also like to have control over who uses your image. Many people believe that by adding a watermark to their images it will stop people, or at the very least deter them, from using their images without permission.

However, there is no real proof that a watermark does indeed reduce this from happening at all. It’s now all too easy to crop a watermark out of an image, or for the more savvy, clone it out altogether. Some thieves may not even bother with any of that; they may just simply take the image, with or without a watermark, and use it. The truth that is once your images are online, you cannot stop your images from being used without your permission – watermark or no watermark.

A watermark on your work looks professional

This is a yes, and no answer. A good watermark can, in a very loose sense, look professional. However, the vast majority of watermarks – at least the ones I’ve seen – bring the level of professionalism right down. They are either simply too big, too distracting, have too much going on, or are poorly designed. They can even be a mix of all those things. A bad watermark can quickly degrade even the best image.

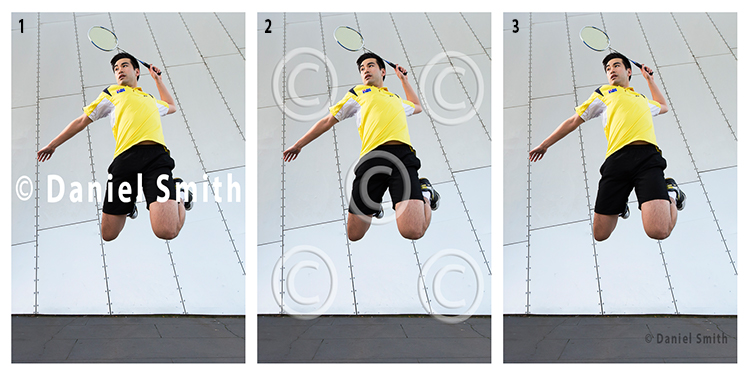

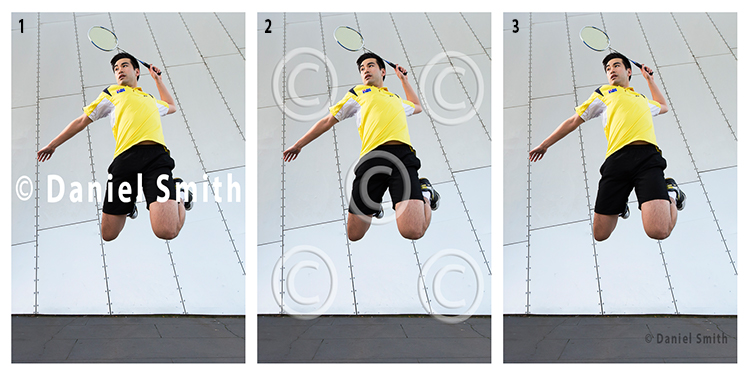

If you’ve decided that you still wish to watermark your work, here’s a quick example of bad, and good watermarks.

Example 1 (above left)

The watermark in the first example here has no reduced opacity, and is also straight across the middle of the image. By having it in that position, it is obstructing the view of the subject. In addition, it is also far too large. This would count as a bad example of a watermark.

Example 2 (above middle)

In this example, the opacity of the watermark has been reduced, which helps the image behind show through more than the first example. However, the watermark covers the entire image. The design is also quite generic which is okay for a stock website, where the images might be sold. But for a personal watermark, it looks too plain.

Example 3 (above right)

This is how a watermark should look; it’s small and discrete. It won’t stop people from stealing the image as it could easily be cloned out. However, if you wanted to try and prevent theft, this watermark could be placed closer to the main subject.

Generally, a watermark should:

- Be small and monochromatic – or have very little color. Large, colored watermarks, detract from the image as they can compete with the subject too much.

- Be placed in a descreet area of the image that does not interfere with the view of the image, but will make it more difficult to remove or clone out.

- Have limited text

- If the watermark is small, then having text will be all but near impossible to read

When and where to watermark

Watermarks can have their place on images. Although, they should not be on every image that you post online. Social media platforms, such as Facebook and Pinterest for example, could benefit with a subtle watermark on your images. In this case, if other users do share your photo, you can at least get a little exposure, provided they do not crop the watermark out.

Another instance where a watermark could be of benefit, is when you are showing images to someone as proofs or previews; perhaps after a wedding, or a model photoshoot for example. In those cases, the watermark could say SAMPLE or PROOF; something to make it known that those images are not the final product. In this scenario, the watermark is not intended to stop the unauthorized use of the images – rather it is there to make it known that, if these images are used, they are not the final product.

On the other hand, if you have a website that you use to show off your work, or even to potential clients as a portfolio, watermarking your images will not be of great benefit, as they generally do not look that professional.

Conclusion

I am of the opinion that watermarks are used all too often nowadays, by photographers who want to get their name out there and prevent the theft or unauthorized use of their work, which is perfectly understandable. However, I believe that in most cases, a watermark does not add any significant purpose to your work. A watermark does not stop anyone from stealing your image, nor can it guarantee that your name will gain greater exposure if your images are shared. Rather, watermarks only degrade the quality of your work as they are most often not designed correctly, and are an obstruction to your image.

The only way that you can guarantee that your work will not be stolen, or used without your permission at all, is to never post or upload your images anywhere on the internet.

I enjoy sharing my work on the internet. But likewise, I like to share work that people can enjoy without the degrading distraction that a watermark provides. What are your thoughts? Do you use watermarks? Please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments below.

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

tablet_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_tab-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78623” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

mobile_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_mob-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78158” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

The post The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly of Watermarks and When and How to Use Them Effectively by Daniel Smith appeared first on Digital Photography School.

Digital Photography School

You must be logged in to post a comment.