The longer you shoot, the larger the repertoire of subjects and assignments you photograph becomes. You start off photographing flowers in the garden, your neighbour’s dog, your sister’s kids, your friend’s wedding and then before you know it you’re doing product shots for your friend’s new company. All this happens over time and there is one pretty fundamental skill that must remain paramount throughout out your process, properly focused images. Sure we’ve all been there, we’ve all taken that shot once in while which is slightly soft (a polite photographer’s term to describe out-of-focus images). But, it’s a great shot so we keep it anyway, even tho we would still have preferred it to be tack sharp.

In focus images have been one of the most fundamental rules of photography right from the dawn of the craft. In the early 1900s it was a craft in its own right, but in the 1960s Leica introduced a rudimentary autofocus system that changed everything. Since then, autofocus has developed dramatically and it’s no longer a feature on cameras, it’s a given.

So, bringing autofocus up-to-date you have a few options to choose from in your modern DSLR. Those are some of the features I will cover in this article, along with when to use them. Both Canon and Nikon have very similar settings, albeit incorporating different technologies the results are very similar. There are also other brands like Sony and Olympus etc., that also follow suit, but here I will be discussing the four main focus modes in Canon and Nikon.

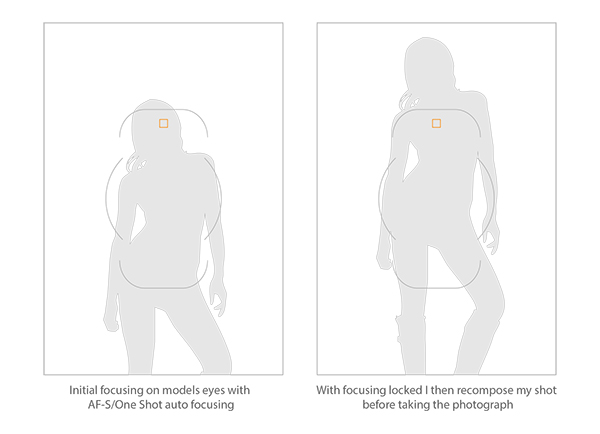

This image above was shot utilizing the AF-S (Nikon) or One Shot (Canon) autofocus mode on the camera. Here I focused on the models eyes and then recomposed my image so that she was over to the left of the frame, allowing for more space in the image in the direction she is looking.

Single Shot Mode

First off, you have the mode that’s probably been around the longest – Canon’s One Shot and Nikon’s AF-S. Both of these will do pretty much the same thing. This mode is predominantly used for stationary objects like model shoots (most of the time – more on when not to use it for model shoots later) and anything that doesn’t require your subject to move around too much in the frame. You half press the shutter in this mode, and then you can recompose the image. For example, you focus on the model’s eyes, then recompose to put her on the left hand side of the image. This autofocus mode will get you through most situations.

Active or Continuous Focus Modes

Next we have the step up from the single focus to Canon’s AI Servo, and Nikon’s AF-C modes. Essentially what this setting does is to continuously track your initial focus point and readjust the focus accordingly. This setting is ideal for moving subjects like active children, and pets that are constantly on the move.

Auto Modes

Finally out of the autofocus settings we have Canon’s AI Focus, and Nikon’s AF-A. Both of these settings actually leave it up to the camera to decide which is best out of the other two focusing modes to use. In this mode it will either choose to continuously track your chosen subject should it decide to move, or focus lock if you would like to recompose. In theory, then I needn’t of bothered explaining the other two settings as surely this is the best of both worlds? Not quite. I personally have tested this mode a fair amount with stop-start subjects and although the camera does a good job of keeping up with them it’s always more accurate to use continuous focus mode. The same also goes for its ability to determine when a subject has stopped and when to focus lock for recomposing. Personally I never use this mode as although it has the best of both, it also has the worst of both.

Image above taken with an 85mm f/1.8 prime lens using manual focus. Shooting in manual focus negates the need to recompose and loose focus in autofocus modes.

So, although I have just covered the three basic settings here very briefly, there is, of course, a whole of host other technological advancements in autofocus that I haven’t covered. I know Nikon has extensive, matrix and 3D autofocusing features. As well most modern DSLR have incorporated the “back button autofocus” which also helps with focus locking. But going over all of that is not the purpose of this article.

Manual Focus Mode

The last focus mode I wanted to cover and one that is rarely used is the Manual focus mode. This mode strikes fear into the heart of nearly all modern photographers and that’s simply because they’ve probably never used it. Do you ever need to use it? That is something that only you can decide and is probably based on the type of photographs you take. If you only ever take portraits of energetic kids or fast paced sports, then autofocus is probably always your go-to mode. If however you shoot still life, architecture, landscapes and other detailed, relatively motionless subjects, then manual focus is probably a good way to go.

There are a few reasons for this. Landscape photographers will want to find the hyperfocal distance of their scene to maximize the amount of in-focus points (depth of field) in the image. This is based on an equation so autofocusing on a specific object is not always the way to go. Still life photographers will usually have their camera locked-down on a tripod so they will not want to focus and recompose once they’ve set up the shot, so it’s just far easier to focus manually. There is also another reason to want to use manual mode on some cameras and certain situations, and that was the catalyst for this article.

This version of the image was shot using the autofocus mode AF-S/One Shot, and meant that after I had focused and recomposed the shot, the model’s eyes were left out of focus.

I recently purchased an 85mm f/1.8 prime lens, and I wanted to test the lens out and see what the sharpness was like at f/1.8. I predominately only photograph models so I set up my test and went about taking some shots at f/1.8 using my usual AF-S/One Shot autofocusing mode. When I got my shots back to the computer to take a look, I was surprised to see that most of them were very soft. It took a few minutes to realize my error and since then I’ve adjusted how I shoot with these parameters.

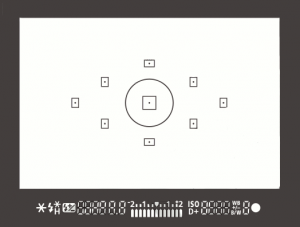

Here you can see that the selected focal node is still situated in the middle of the viewfinder even though I have elected the outer most one when shooting in the portrait format.

I haven’t done a lot of very shallow depth of field shots up until this point so I hadn’t seen the now exaggerated results of my

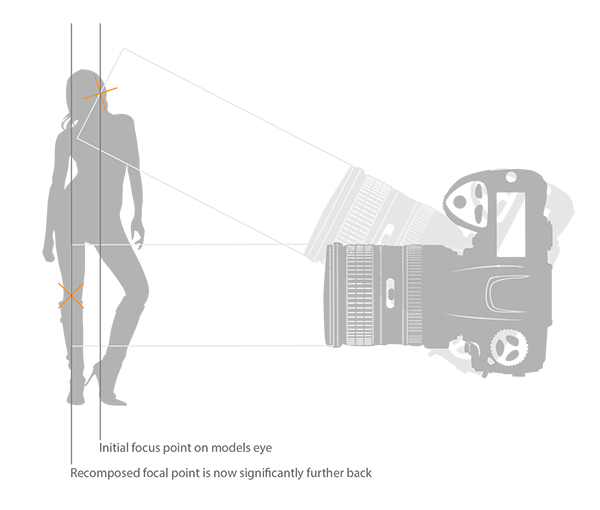

poor focusing technique previously. At f/1.8 you have a very, very shallow amount in focus (depth of field). For example, a head shot with the eyes in focus, the tip of the subject’s nose will be out of focus. For the test I was photographing the model at 3/4 length and shooting up at her so my camera height was probably about her waist height. I was about 6 feet (2 meters) away from her and I was focusing on her eyes with my focal point in camera then recomposing my shot to capture the 3/4 length crop. The problem with most cameras is that although they have a lot of focusing points, they’re all clustered in the centre of the viewfinder so even though I chose the outer most focal point I still have a dramatic amount of recomposing to do.

The diagram above clearly illustrates what’s actually going on when you recompose an image after focusing in AF-S/One Shot autofocus mode. The actual part of the image that was in focus, is now out of focus.

This isn’t normally a noticeable problem when recomposing at f/16, but at f/1.8 that dramatic shift in the focal plane means the resulting image is very soft around the model’s eyes. As I recomposed it actually repositioned my focal point further back behind the model, meaning the back of her head and hair were in focus but not her eyes.

There aren’t too many ways around this pesky little issue, especially as you may not notice it on the back of the camera’s little screen. One thing that did resolve it though was by switching to manual focus. I could then compose my shot and manually focus on the model’s eyes, resulting in a fantastically sharp image where I wanted it to be sharp.

Granted there were a few things conspiring together here to really exaggerate the issue. Firstly, I was shooting at f/1.8, that’s always going to rely on critical sharpness. Secondly, I was down low shooting up. This always exaggerates the focal plane shift when recomposing and lastly I was stuck with limited focal nodes. There are many technical reasons why modern DSLRs don’t allow focal nodes towards the edges. A lot of smaller frame cameras like the mirrorless, APS-C and micro 4/3 cameras all have selectable focal nodes covering the viewfinder, but alas, DSLR technology isn’t there yet. Until it is, it’s a good idea to be aware of what’s going on in autofocus modes on your camera, and be prepared and ready to switch to manual focus when required.

Good Luck!

The post Getting Sharper Images – an Understanding of Focus Modes by Jake Hicks appeared first on Digital Photography School.

On most SLRs, and some of the mirrorless or four thirds cameras, there is an option of selecting what point it uses to focus. Meaning, when you look through the camera and see some flashing dots or squares (or something similar to the image on the right), those are your focus zones or spots. Make sure it is NOT set for the camera selecting which of those spots are targeted for focusing. When the camera chooses where to focus it can often pick the wrong thing. If you have a subject that is behind something in the foreground the camera will usually pick the closest object, which is not your intention, and you’ll end up with the wrong thing in focus.

On most SLRs, and some of the mirrorless or four thirds cameras, there is an option of selecting what point it uses to focus. Meaning, when you look through the camera and see some flashing dots or squares (or something similar to the image on the right), those are your focus zones or spots. Make sure it is NOT set for the camera selecting which of those spots are targeted for focusing. When the camera chooses where to focus it can often pick the wrong thing. If you have a subject that is behind something in the foreground the camera will usually pick the closest object, which is not your intention, and you’ll end up with the wrong thing in focus. Most cameras have a few different types of focus modes. On Canon you’ll see them as Single (One Shot), AI (stands for Artificial Intelligence) Focus and AI Servo. On Nikon the modes are AF-S, AF-C and AF-A. Choose the one that bests fits for the subject you’re photographing.

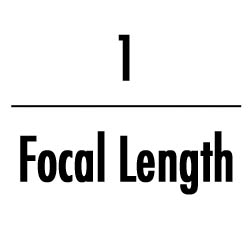

Most cameras have a few different types of focus modes. On Canon you’ll see them as Single (One Shot), AI (stands for Artificial Intelligence) Focus and AI Servo. On Nikon the modes are AF-S, AF-C and AF-A. Choose the one that bests fits for the subject you’re photographing. There is much debate about this subject in terms of how slow is too slow for hand holding your camera. Some instructors will say 1/60th of a second, I tend to use another rule of thumb which is 1 over the focal length of your lens. So if you are shooting with a 200mm lens, then 1/200 is how fast you need to be shooting to get rid of blur caused by camera shake. The longer lens you select, the more amplified any movement will become. If you are shooting with a cropped sensor camera, remember that 200mm is now acting like a 350mm so that changes your minimum shutter speed to 1/400. If you use a lens that has image stabilization then you can often stretch it a little bit more, say one or two stops, depending on how steady your hands are. You also want to make sure you are holding your camera in the most stable position with your left hand UNDER the body and lens (sort of cupping it) and both elbows in tight to your body. Then, hold your breath and shoot!

There is much debate about this subject in terms of how slow is too slow for hand holding your camera. Some instructors will say 1/60th of a second, I tend to use another rule of thumb which is 1 over the focal length of your lens. So if you are shooting with a 200mm lens, then 1/200 is how fast you need to be shooting to get rid of blur caused by camera shake. The longer lens you select, the more amplified any movement will become. If you are shooting with a cropped sensor camera, remember that 200mm is now acting like a 350mm so that changes your minimum shutter speed to 1/400. If you use a lens that has image stabilization then you can often stretch it a little bit more, say one or two stops, depending on how steady your hands are. You also want to make sure you are holding your camera in the most stable position with your left hand UNDER the body and lens (sort of cupping it) and both elbows in tight to your body. Then, hold your breath and shoot!

You must be logged in to post a comment.