A challenging nighttime scene was overcome with multiple exposures and layer masking.

Blending indoors and outdoors in architectural photography can often create a compelling image. Unfortunately, however, it is often fraught with exposure and white balance issues. These issues are compounded at night, when artificial lights inside buildings coupled with the darkness of the night sky create an especially contrasty image with an unattractive colorcast created by the different light sources. Luckily, with multiple exposures and layer masking in Photoshop, you can create a photo that looks a lot like what you saw with your own eyes.

This method is a little different than HDR, which involves taking three or more photos at different exposures, then using automated software to combine them into one image that captures the range of light in the scene. Here, you’ll be taking three or more photos and blending them manually, since HDR software often creates unpleasant artifacts and odd color blending when used in the type of situations presented in this tutorial. You can always try HDR software first, and if the colors don’t seem to bleed, you can skip down to the later part of the tutorial for dealing with the colorcasts.

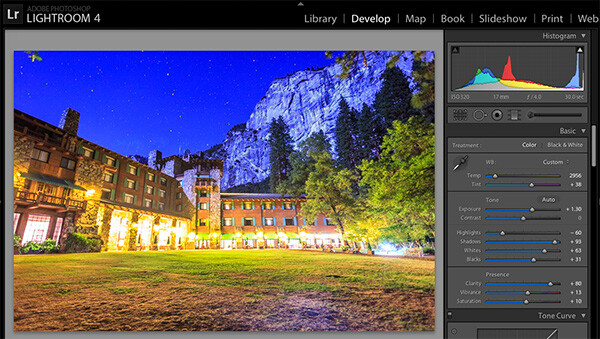

An image that required three exposures and had a color cast from the lamps.

Shoot three or more exposures on a tripod

You need to shoot as many photos as it takes to capture the dynamic range (the range from light to dark) in the scene. It is really important to shoot in RAW, to get as much mileage out of each photo as possible. A tripod is also necessary, since you’ll probably be taking these at night, and also because you won’t be using HDR software which aligns the images. You can use auto exposure bracketing to capture three images, but at night, exposures on the high end can often exceed 30 seconds, the longest shutter speed most cameras will let you shoot manually. It’s probably easiest to use manual mode, set your ISO to 100 or 200, stop down your aperture to f/7.1 or f/8 (if it’s really dark out, you can open it up wider), and then take a series of shots at increasingly slower shutter speeds until you’ve captured the range of light in the scene. If you need to go past 30 seconds, go into bulb mode (consult your camera’s manual for how to find it), and use a remote trigger release, holding the shutter open as long as you want. Don’t worry about white balance yet.

Processing one of the RAW files in Lightroom. Here you can see where just processing one RAW file wouldn’t be sufficient.

Process each exposure in Lightroom or Camera Raw, then open as layers in Photoshop

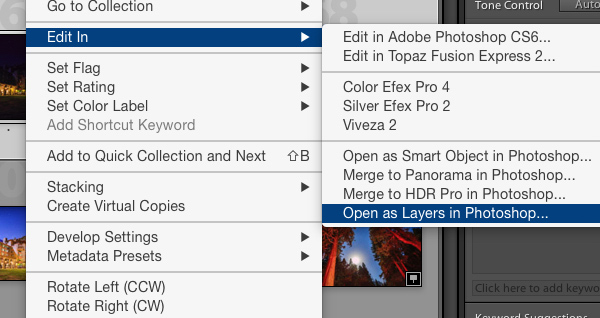

First, you are going to process the photos for exposure only, ignoring white balance. If you don’t have Lightroom, you can do this in Adobe Camera Raw. Since you have multiple exposures, you don’t need to go crazy trying to recover lost highlights (overblown bright spots) and shadows (dark parts that look black), but you want to recover them a little bit to give you more leverage later on in the process. There’s no magical formula for processing here. I usually apply lens profile correction, remove chromatic aberration, and do a little noise reduction before bringing down the highlights a little bit and bringing up the shadows and whites a little bit. Once you’re done processing each exposure, select them all, right click, and select “open as layers in Photoshop. Now you’ve got an image with three or more layers all ready to go, but we’re no quite ready to do the layer masking yet.

Go back and reprocess for white balance

White balance is a setting that keeps the whites in the image white, removing any colorcasts. Different light sources have different white balance settings though, so if you have a photo with two or more different light sources (such as the night sky and an artificial light), no matter how you adjust your settings, you’ll always have a color cast somewhere on your photo. What you’re going to do here is reprocess each photo so that you’ve corrected any colorcasts. If you’re lucky, you’ll have no more than two light sources in the photo. Unfortunately, though, there can often be more.

It’s important to note that you only have to correct for colorcasts that are in properly exposed parts of each photo. For instance, in one of your overexposed photos, don’t worry about the white balance for the overblown highlights. You’ll be discarding that part of the photo later. For one of your underexposed photos, don’t worry about correcting for the shadows, since you’ll also be discarding that. Start with your most properly exposed photo, and correct for any colorcast you see (for instance, the lights inside a building have a yellow cast).

All you have to do to correct the white balance is slide those two sliders (one goes from blue to yellow, and the other goes from green to magenta) until the part of the photo with the colorcast looks normal. When you’re done, open that photo in Photoshop, and make it a layer in the other image you have open. Do this by hitting Ctrl-A on Windows, or Command-A on a Mac to select the photo you just opened, then Ctrl-C or Command-C to copy it. Then click on the image with the three layers, and hit Ctrl-V or Command-V to paste it in as a layer. Repeat the processing until you have corrected all colorcasts in the photo. Then, move on to the other exposures, and correct any color casts there (remember, only the properly exposed parts need to be corrected).

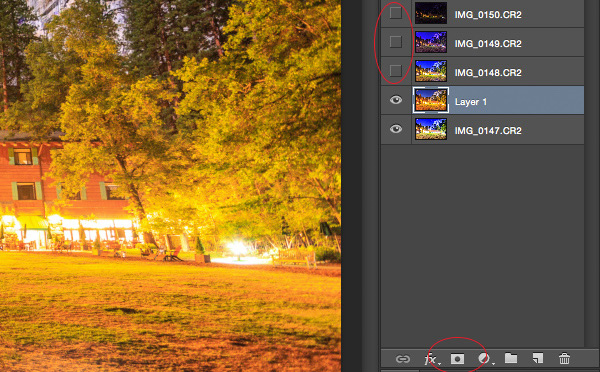

Mask in one layer at a time

Once you’ve finally got every exposure and every colorcast accounted for as separate layers, you’re going to mask them in one by one. I start by making all but the bottom two layers invisible and masking in one layer at a time (by the way, the order of the layers does not matter, but having the most properly exposed image on the bottom will probably make things easier). Do this by clicking the little eye to the left of each layer except the bottom two. Then, with the layer one up from the bottom selected, click the layer mask icon (it’s a rectangle with a dot in the middle, found at the bottom of the layer panel). Make sure the paintbrush icon is selected as well (this can usually be found on the left hand side). You may need to adjust your brush size as you go through.

When painting with black on the layer mask, you will cover up the parts of the layer you don’t want appearing (the improperly exposed or color cast parts of the image are what you want to cover up). When you want to go back and reveal parts because you’ve made a mistake, paint with white on the layer mask. Click X on your keyboard to toggle back and forth between black and white.

When you’ve masked out all the parts of the layer you don’t want shown, select the layer on top of that and make it visible (click the space where the eye used to be). Then create another mask and start masking that layer. Keep revealing layers and masking them in until you’re done. In some cases, one part of the photo may be properly exposed in more than one image. In this case, keep the one that looks better to you. Once you’ve finished this process, save the photo as you would normally. If you think you might come back to this photo later and edit it, make sure to save a copy as a PSD.

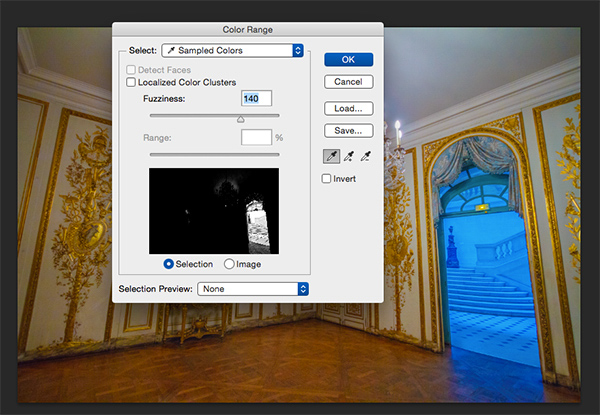

Sometimes you get lucky, and the part of the image that’s colorcast has a very strong hue to it. If you have a colorcast that’s almost all one color, you can automate the masking process a bit for that layer. In the top pane, go to Select –> color range, then click somewhere in the colorcast. Look at the preview. You want the part of the image that’s your colorcast to be almost completely white, and the rest to look almost completely black. Adjust the fuzziness slider until this is the case, and then click ok. You actually want to select the inverse of that, so go to Select –> inverse. Now click the layer mask icon, and you’ll have a mask that hopefully masks out the colorcast. If it doesn’t look right, undo it and try it again with a different fuzziness setting. This is not a perfect fix. You will still need to do some fine-tuning, but it really helps move things along quicker.

A simple “select color range” layer mask got rid of most of the colorcast in this photo.

Conclusion

This is just one method of conquering the challenges brought on by nighttime architectural photography. As you start working with photos of this nature, you may find a different method that you prefer. Luckily, many photos only require some of the steps detailed in this tutorial. Sometimes you only need one exposure, but you need to process for colorcasts. Other times, the white balance is even, but you need to mask for exposure. It takes practice to master these intricate masking techniques, so don’t give up if you’re unhappy with your results at first. Start with simpler photos with fewer colorcasts and exposures needed before diving into a really complex one. In time you’ll be creating photos that look as natural as they appeared when you saw them in person.

A single exposure that required layer masking to correct colorcasts.

Have you got any tips for doing architectural photography or using layer masking? Please share in the comments below.

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

tablet_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_tab-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78623” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

mobile_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_mob-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78158” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

The post Architectural Photography Using Layer Masking to Correct Contrast and White Balance by Samantha Decker appeared first on Digital Photography School.