The post Getting to Grips with Fill Light in Portrait Photography appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by John McIntire.

Using fill light is an essential skill that will allow you complete control over the contrast and tonality in your images in any type of lighting situation.

It should be no secret to any photographer that one light is all you need to achieve great results. While one light setups (in this context, specifically those that don’t involve the use of a reflector) are both well discussed and incredibly useful, sometimes it’s good (or even essential) to go beyond the basics. The next step in your progression is probably going to be to add fill lighting.

Fill light is one of those essential skills that every photographer should have a good grasp of no matter what type of light they are using.

One light setups are powerful, and the results can be great. However, sometimes it’s useful to be able to take even more control over the contrast in your images.

This article will help to get you started with two types of fill lighting. The first of these is the use of the humble reflector. The other is to use a second dedicated light source. Both of these methods are very different in how they are implemented and what they can achieve. Mastering both will give you a more complete skill set with which to use in your photography.

What is fill lighting and what does it achieve?

In the image on the left, the lack of fill lighting has left most of the details in the back of the subject’s dress as pure black. Adding fill light (right) has brought those details back.

The concept of fill lighting is quite simple.

The idea is that you use it to light the shadows in your frame. What this does is:

- Brings up the exposure of the shadow areas in your image.

- Reduces overall contrast in your frame (much like landscape photographers use graduated ND filters to reduce contrast in their images).

- Brings your final images more in line with how the eye sees the world, rather than the limited range of your camera’s sensor.

While really dark and contrasty images definitely have their place (I love them myself), images (especially portraits for clients) will benefit from a more even contrast ratio. I once heard it described (I’m sorry, I don’t remember where) that in lighting for TV and cinema, the shadows are always lit. This was a lightbulb moment for me as I had always wondered how cinematographers seemed to show a lot detail while still retaining a good amount of contrast. The answer was controlled fill lighting.

Two types

Reflectors

Reflectors are a powerful and versatile tool that allows you to be as subtle or as bold as you like with your fill lighting.

The most basic type of fill lighting is that provided by the ever so basic, yet powerful, reflector. You probably have at least one of these already (or you’ve made a few). Reflectors provide fill light by reflecting light (go figure) from your key back into the shadows of your frame. In a lot of cases, reflectors will be your first foray into fill lighting. However, they will also be one of your most-used pieces of kit altogether.

Secondary lights

Using a secondary light source as fill is going to be your most versatile option.

You can also use a second light (or third and beyond) as your fill light. A dedicated fill light will do the same basic job as a reflector, but it is infinitely more controllable. You can fine-tune the exposure and shape of your fill light with a precision that reflectors just don’t allow.

Contrast ratios – The very basics

Left: The shadows are filled heavily and the fill light is metered one-stop below key. This results in a low contrast image with shadows retained. Right: the fill here is four stops below key. The contrast is high and the shadows are deep, but all of the detail is present.

The very concept of a contrast ratio can seem technical and daunting, I know. However, it is not at all that difficult of a concept and it’s just not that technical. At the most basic level, a contrast ratio simply tells you how bright one light is in relation to one another in terms of the aperture of your camera.

If your key light is metering at f/8, that means that if you set your camera to f/8 and an appropriate shutter speed (lower than your camera’s max sync speed) you will achieve a correct (subjective) exposure in-camera.

Fill lighting will always be underexposed in relation to your key light. If it’s even to your key light, you will get flat, no-contrast images as a result. For a contrast ratio that provides low contrast, you will want your fill light to be at least one stop darker than your key light. Since our hypothetical key light is f/8, that means the key light in this instance needs to meter f/5.6. This is a ratio of 2:1 (which is more advanced and you definitely don’t need to know to get started).

In short, if you want less contrast, your fill light should be one to two stops under your key light. If you want more contrast, try three to four stops.

Metering

If you want to be as precise as possible with these ratios, you will want to consider a light meter. That way you can measure any light falling on the scene with the press of a couple of buttons. This is the easiest way to go about it and works in the studio and natural light. You can also meter the light bouncing off a reflector.

A light meter is the easiest and most accurate way to read what your light is doing. However, they don’t tend to be cheap.

That does not at all mean that you have to use a light meter, though. While more difficult (especially if you’re new to lighting like this), you can do it with your histogram on the back of your camera. Take a test shot with just your key light on. Now take one with only your fill light on. (Note: you won’t be able to do this if you are using a reflector.) Because fill lighting should be raising the exposures on your shadows, the shadow area of the histogram of your fill light test shot should be further to the right than that of your key light test shot. If the shadow areas on both histograms line up, you need to increase the exposure of your fill light. If the shadow areas of your fill light’s histogram line up with the mid-tones or highlights of your key light’s histogram, you need to decrease the exposure of your fill light. (I did say it was trickier.)

Left: Without fill light, you can see the shadows are underexposed. Right: With subtle fill light, you can see the shadows are brought up quite a lot.

Of course, you don’t have to do either of these things. You can always eyeball the whole setup and try to adjust things on the go. I would say this is perfectly fine with experience, but as you start out, I encourage you to at least have a go with the previous methods. It will drastically reduce the amount of time it takes you to get to grips with the technique and fully understand what is going on with your light. The more you understand, the easier you will find it to adjust things on the fly. You will also be able to learn new techniques faster.

Fill light with reflectors

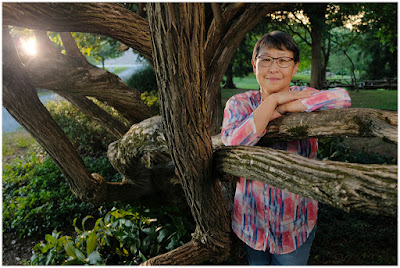

Reflectors can be subtle or bold when used as fill and are pretty versatile for what they are.

Reflectors are:

- Cheap

- Easy to setup

- Easy to use

- Very effective

Getting started with reflectors as fill lighting

Reflectors are powerful, yet accessible, tools for fill lighting.

Before you start to think about fill, you will want to decide what your key light (main light source) is going to do. Set up your key light so that it is shaping and lighting your subject the way that you want. Meter so that you have the exposure settings that you desire.

A small(ish) softbox placed in front of and above the subject creates soft light with shadows underneath the subject’s features.

Now, evaluate the shadow areas that your key light is creating. If you’re using natural light, or strobes fitted with modeling lights, you can do this by eye. Alternatively, you can take a test shot and review it on the back of the camera.

Here you can see that while the light is soft, the shadows are a prominent part of the image.

Place your reflector so that it is roughly opposite your key light. Evaluate what the reflector is doing (either by eye or test shot again).

Adding a reflector beneath the key light serves to raise the exposure in the shadow areas of the image.

What you are aiming for is for you shadows to be brought up in exposure, but not eliminated altogether. If you want low contrast, bring your reflector in as close as possible. If you want more contrast, move it away.

With the reflector used as fill, the shadows are still present, but the overall contrast in the image has been reduced.

It can take quite a lot of practice before you learn to see the subtle changes a white reflector provides. The key is to get as much practice in as possible.

Set up an object and light it. Put your reflector wherever you want and start taking shots, being sure to move the reflector into different positions each time. Review each shot and try to notice the behavior of the light in each instance. This exercise will give you a pretty good idea of how a reflector is going to behave in any given situation. Do this exercise often and you will find you can see even the most subtle shifts in light where it was difficult before.

Another quick tip to help you see the difference in contrast in a scene is to squint. It sounds ridiculous, but squinting reduces your vision to blocks of value and you will be able to see the contrast in the scene more easily.

A second light

A second strobe serving as fill gives you the most control over how you manipulate your shadows.

Like reflectors, using extra lights as fill is a fundamental skill, albeit one with a slightly steeper learning curve. That said, unlike reflectors, using a dedicated light source allows you full control over the power output, making it much easier than a reflector to control how the light is going to behave.

Varying degrees of contrast between your shadow and highlight tones are possible just by adjusting the power of your fill light.

To get started using a dedicated fill light, place your key light in your desired position and set the power for your desired aperture. Let’s return to that hypothetical of f/8.

Here, a softbox is placed at 45 degrees to the subject.

Knowing your aperture, place your fill light where it will affect the shadows in the manner you would like and set the power output so that it will be underexposed in relation to your aperture. How much you underexpose for is entirely up to you. If you want, say, two stops of fill in this scenario, then you will want your fill light to meter at f/4.

A 7′ parabolic umbrella with diffusion was added about 10-feet away to serve as fill. It was set to meter 2-stops under the key light.

Take a test shot and see if you have your desired effect. Adjust as required and there you go.

In this before (left) and after (right) you can see how the shadows on the right side of the image are lifted and filled in with the fill light.

Taking it further

You can design fill lighting however you like. Feel free to use multiple sources of different sizes and shapes if it works.

Of course, you are not limited to a single fill light. You can have multiple fill lights lighting your subjects from both sides. You can also mix lights and reflectors for different strengths of fill lighting from various angles. You can pretty much do whatever you want in terms of designing a light set-up. You are only limited by the equipment you have at hand and what you can dream up.

Using multiple fill lights allows you to control every aspect of contrast in your images.

An idea is only crazy if it might work and you don’t try it.

Tips for fill lighting

1) It’s often better to retain the shadows rather than fill them in completely. This is not a rule, but images that retain some amount of contrast are often more natural and pleasing to the eye.

2) Pay attention to the catchlights in portraits – Extra light sources mean extra catchlights. When you are setting up your lights (reflectors included), be sure to watch the catchlights in your subjects’ eyes. Catchlights can make or break a portrait, so make sure you are controlling them as much as you are the lighting itself.

3) Big light sources at a distance work very well as fill light.

This is by no means a rule, but big light sources (like the 7′ umbrella to camera right) from a distance work really well as fill lighting.

4) Don’t be a slave to the ratios – While using the ratios as a starting point can, and will, be a useful springboard, that doesn’t mean you should adhere to them rigidly. If something isn’t right, adjust as you see fit. Nobody cares in the end if your ratios are exactly 4:1, but they do care if your photos look right. Use your best judgment and change things up if you need to. Sometimes only the tiniest of power adjustments will completely change the end result.

5) Think outside the box – Any light source can be your key and your fill. You’re probably aware that you can use flash to fill-in shadows in natural light, but you can also use natural light as fill where your main lighting is provided by flash.

Here, the key light is a large window to the camera right. The fill light is provided by a strobe. You can mix light sources however you want to achieve your fill lighting.

That’s it

Hopefully, that’s served as a primer to get you started and demystify fill lighting. Being able to control the contrast in your images with lighting is a fundamental skill that you will be able to use across multiple disciplines. It will allow you to bring a new level of depth to your images straight out of the camera.

Get out and practice, start simple and go slow, and you will master the basics in no time at all.

Try out some of these tips, and share your photos with us in the comments!

The post Getting to Grips with Fill Light in Portrait Photography appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by John McIntire.

Digital Photography School

You must be logged in to post a comment.