A trip to photograph Northern Lights (also called The Aurora Borealis) often tops the wish list for many photographers. For good reason too; the aurora is a natural phenomenon unlike any other. Lights dancing over the frozen winter landscape is ethereal, beautiful, and at times, jaw-dropping. Living in Alaska has provided me the opportunity to shoot the lights more often than most, and yet more than once, I’ve had to stop clicking and just watch the curtains shift and dance. In fact, let that be my first tip if you are planning an aurora

In fact, let that be my first tip if you are planning an aurora photo shoot – occasionally just stop and watch. Seriously, put that camera down for a moment and relish the sight. Okay, now let’s figure out how to photograph the Northern Lights.

Gear

Tripod

You need one. There is no faking this one, get one and use it. If it’s brutally cold (which, let’s face it, it probably will be) you’ll appreciate carbon over cold-channelling aluminum, but either will work. Bring it, use it, no excuses.

Camera

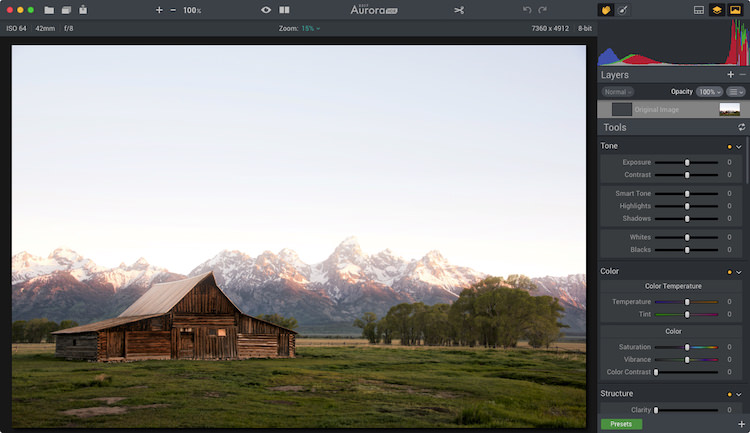

I’ve seen beautiful images of the Northern Lights made with everything from good point and shoot cameras to high-end mirrorless and DSLRs. So don’t feel too restricted by your choice of camera. That said, a camera with low noise at high ISO is definitely preferable. Though not absolutely necessary, the ability to change lenses, too, is a major asset.

Lenses

As a general rule, you want a lens that is wide and fast (has a large maximum aperture). The faster the better. My primary aurora lens is a 14mm f/2.8, but I’m eyeing a 20mm f/1.8 for the extra speed. All lenses will need to be manually focused, so make sure that is straight-forward. A variety of focal lengths, either in the form of a zoom, or a choice of lenses is also helpful. I’ve used everything from a 70-200mm to my fixed 14mm to photograph Northern Lights.

I’ve got to admit, living in the far north has its advantages. I merely needed to step out my front door to make this image. (If you are wondering what that strange U-shaped white form in the sky is, it’s the exhaust trail from an aurora research rocket fired off by the University of Alaska Fairbanks).

Remote Release

Though not absolutely necessary, a cable or wireless release for your camera will help reduce camera shake when you click the shutter. A jiggly blur in the stars can ruin an otherwise good shot. If you don’t have a release, use the camera’s self-timer, many have a 2-second setting which is useful. Keep in mind that using a timer rather than a release will slow you down.

Clothing

Maybe I should have put this one at the top of the gear list, because it is probably the most important thing for a successful winter shoot of any kind. Right now, as I’m writing this article, I’m sitting in a cabin 70 miles north of the Arctic Circle in the Brooks Range of northern Alaska. I’m leading an aurora photo tour, and the warmest night-time temperature we’ve seen so far was -35F (-37c). Good clothing has not just been important, but vital.

Right now, as I’m writing this article, I’m sitting in a cabin 70 miles north of the Arctic Circle in the Brooks Range of northern Alaska. I’m leading an aurora photo tour, and the warmest night-time temperature we’ve seen so far was -35F (-37c). Good clothing has not just been important, but vital. I don’t want to go into too much detail here, but a thick down coat with a hood, down or synthetic fill pants, mittens, liner gloves, face masks, and warm hats should all be on your list.

That said, I do want to take just a second to talk about footwear. Trips like the one I’m currently leading are not the time to toy around with light winter boots. This is not the time for fashion. Pack boots, god-ugly bunny boots, mukluks, and other extreme-cold footwear, a couple sizes too big (to account for thick socks and toe warmers) are what you are looking for. Nothing will wreck a night of photography more quickly than painfully cold, or (please no) frost-bitten toes. Enough said.

Interesting foregrounds are an important part of any image, and aurora shots are no different. In this case, I climbed a rock outcrop and used a wireless trigger to make this image.

The Day Before

Prefocus – autofocus rarely works in the dark, so you’ll need to manually set your focus. The first thing I do when I’m leading a photo workshop or tour is to take my clients out in the daylight, before our first night chasing the lights, and have them set their focus to some distant mountaintop. After making sure it is tack sharp, I hand out small pieces of electrical tape and have everyone tape the focus in place so it won’t shift around accidentally.

With the excitement of the first aurora show, no one has to worry about messing with their focus points, or worse, find their shots heartbreakingly soft. A caveat: You still need to check your focus periodically. I’ve found that some lenses will shift their focus point slightly when there are extreme temperatures. Pixel-peep occasionally and adjust as necessary.

When the lights are directly overhead, sometimes pointing your camera straight up can be the best option.

In the Field

Have patience. The aurora is a fickle lover, and she only appears when she wants. Even when the forecasts are coming together and everything seems set for success, the lights may take awhile to appear, they may erupt when you don’t expect it, or clouds may obscure the sky. Plan several nights to account for bad weather or uncooperative conditions. Be prepared to stay up late, and again, be patient.

Exposure

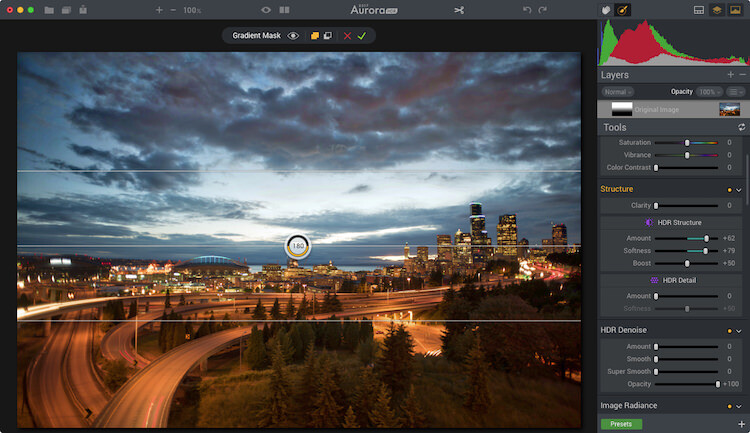

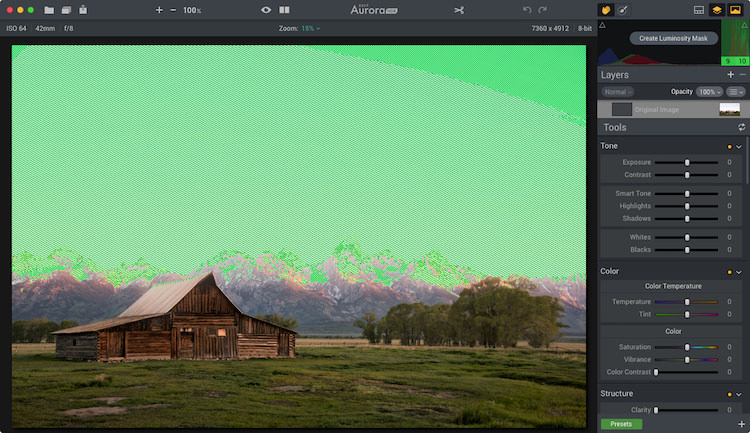

This is one of my first images of the aurora. The lights were bright, and while I managed to capture some color, the 20-second exposure blurred the details into an indistinct curtain. I know better now.

In the days of film and early days of digital, long exposures of 15 or 30 seconds for the aurora were the name of the game. This allowed the lights to appear bright and colorful, but details within the aurora, the pillars, and beams blurred away leaving behind an indistinct curtain. Technology has moved beyond this.

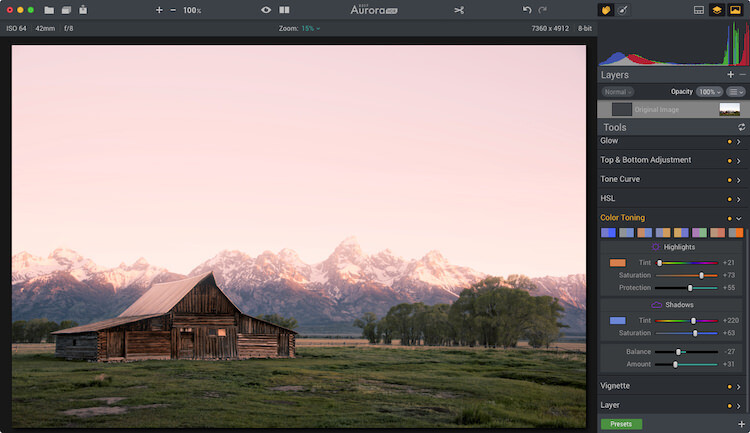

You want the shortest shutter speed possible that allows sufficient brightness and low noise. ISOs in the 1600-6400 range are typical. I start with a setting of f/2.8, ISO 1600 or 3200, for 5 seconds. From there, depending on what the lights are doing, the amount of moonlight, and other factors, I’ll adjust up and down.

Last night, for example, for about 10 minutes the lights brightened and started moving VERY fast. Sacrificing some noise, I went to ISO 6400, f/2.8, and a 1-second exposure. The shots needed a bit of noise reduction in post-processing, but I was able to capture the details of the curtains, and that sharpness in the aurora makes the images successful. A shutter speed just a second or two longer would have blurred the lights.

In contrast to the previous image, for this shot of a very fast moving display, I used a shutter speed of just one second at ISO 6400, f/2.8. As a result, the pillars of light and details in the curtains are sharp.

Composition

When the aurora is hopping, your attention will shift to the sky and away from the foreground. This is natural, but try to pay attention to your composition, just as you would with any landscape image. In the dark, a poorly framed image may not stand out the way it does in daylight. But, I’ll guarantee that you’ll notice when the photos appear on your computer the next morning, and you’ll kick yourself.

Consider where you are, provide some context, avoid distractions, and compose carefully.

A red aurora is a very rare thing indeed. Of the hundreds of nights I’ve spent shooting the Northern Lights, this one had the deepest, brightest reds I’ve ever seen. (FYI, I used my headlamp to light paint the trees in this image.)

Where and When to Photograph the Northern Lights

Choosing the right location for an aurora trip is a big decision. The Aurora Borealis can be seen around the planet’s northern regions. Scandinavian countries, Iceland, northern Canada, and of course Alaska, are popular destinations. While your budget and available time may limit you, it is important to consider the likely weather conditions, local tours, lodging and transportation options, and seasons.

The aurora is primarily a winter phenomenon. In the far north, nights don’t get dark enough in the summer for the lights to appear. Here in Alaska, you can see the lights from late August or early September through mid-April, but prime time is late September through early April.

The nearly full moon in this image was not enough to blow out the bright display of lights, but it takes strong aurora to overcome a full moon. Moonlight is great for foregrounds but can cause issues with visibility of the Northern Lights. If you are shooting the aurora for the first time, I recommend making your trip around the new moon.

Research weather patterns. Some months are more likely than others to have clear skies. In Alaska, March is the driest month with the best chance for clear skies, but other locations will differ.

Moonlight is another thing to consider. While great lights can occur regardless of how bright the moon is, during the dark nights of a new moon, even low-grade aurora displays will appear more distinct against the darker sky.

Getting Help

One of my clients on an aurora photo workshop photographs the northern lights in the Brooks Range of northern Alaska.

Like any discipline of photography, learning to shoot the aurora takes practice. This can make aurora photography a frustrating pursuit for people new to it or with limited time. Organized workshops or tours, or private photo-guide services are a great way to assure some success. Even if you prefer to shoot independently, hiring a local expert for a night to get you started may help you dodge the usual pitfalls and find the best locations to shoot.

Patience Pays Off

Last night it was bitterly cold here in the Brooks Range. We started the night about 9:00 p.m. by driving 50 miles north to a spot high above tree line, a stone’s throw from the continental divide. There, we waited in the moonlight for the Northern Lights to appear. They didn’t, not for the three hours we sat patiently watching the sky. I had a sinking feeling that we were about to get skunked.

Half past midnight we gave up, turned around, and headed back to our rented cabin. Another hour later we pulled in and started unloading the gear. I glanced toward the sky, and there, sure enough, was a single, pale band of northern lights. It was nearly 2:00 a.m., and I’ll admit, my warm bed was sounding really good. But stubbornly, we reloaded our camera bags and tripods and drove a few miles back up the road where the mountains loomed close. When the lights exploded 20 minutes later, we were ready. Our cameras popped in the frigid air as the aurora swirled. We made some of the best images of the trip there.

Be Ready

We were patient, had the right clothing to handle the -40 temperatures, and had our cameras and settings ready. That’s really the core lesson here: be ready. The lights sometimes don’t last long and if you are fiddling with camera focus, or clothed improperly, you’ll miss it. However, preparation and research will greatly increase your chances of success. A chance to photograph Northern Lights, or simply observe them, is not an opportunity to squander.

The post How to Photograph Northern Lights (The Aurora Borealis) by David Shaw appeared first on Digital Photography School.

Digital Photography School

You must be logged in to post a comment.