Shooting interior architecture photography can be challenging to get just right. Here are six tips to help you have more success with this type of photography.

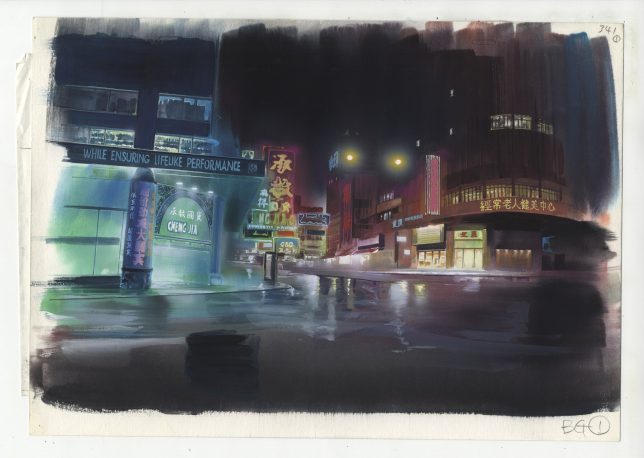

21mm focal length, f/11, ISO 100, 1/200th. One off-camera flash used.

1) Always use a tripod

There are two main reasons why you always want to use a tripod for architecture photography.

First, a tripod will perfectly stabilize your camera/lens setup, which fully mitigates any possibility of motion blur from hand-holding the camera. Additionally, if you’re on a tripod, it’s much easier to make sure your camera is level (I’ll discuss the importance of a level camera later in this article).

Secondly, there’s no good reason NOT to use a tripod (I follow the general rule that, unless there’s a good reason not to have a tripod, I always use one). If you were tracking subjects which required quick movement and recomposition, then a tripod would be a hindrance. But, for architecture photography, your composition will always sit nice and still for you, giving you all the time in the world to set the shot up right. The ideal situation for a tripod.

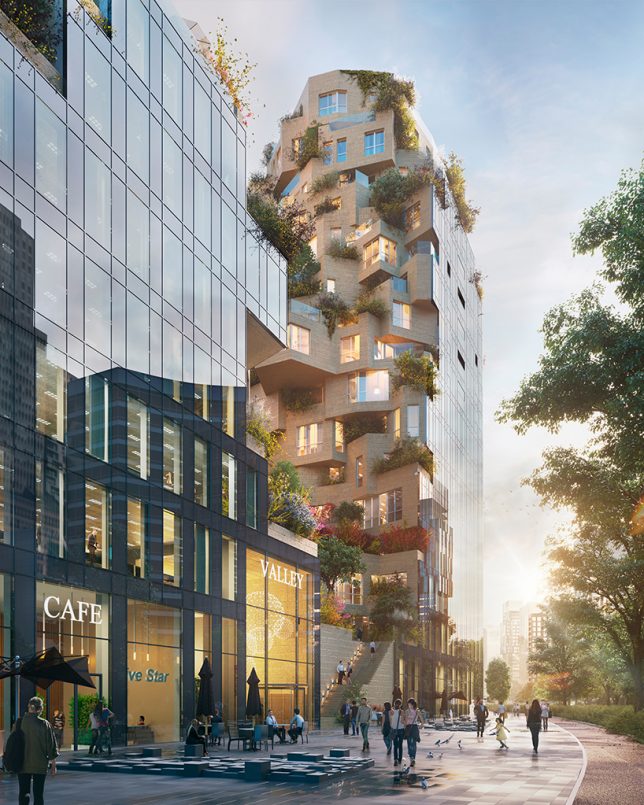

21mm focal length, f/11, ISO 100, 1/120th. One off-camera flash used.

2) Whenever possible, use a flash

If you shoot a room indoors without a flash, you will typically get shadows scattered around the room. Using a flash for interior architecture will help balance the exposure across the entire frame.

This is how I typically use a flash. Put the flash on a tripod or a stand, and place it a few feet away from the camera (on each side of the camera if you use two flashes for larger rooms), and a foot or so behind the camera. Aim the flashes so they are pointing up at the ceiling, but also slightly away from the room you’re shooting. At this angle, the light from the flashes will illuminate the room indirectly (i.e. bouncing off the ceiling and walls), creating a soft, even, fill-in light for the room you’re shooting. Set the flashes manually at half power (one stop below full power) and fire away!

This was a tricky shot because my flash was reflecting off the windows no matter where I positioned it. So I took two shots (one with flash and one without) and masked them together in Photoshop. The windows you see in this image are from the shot without a flash, while the rest of the room is from the shot with the flash.

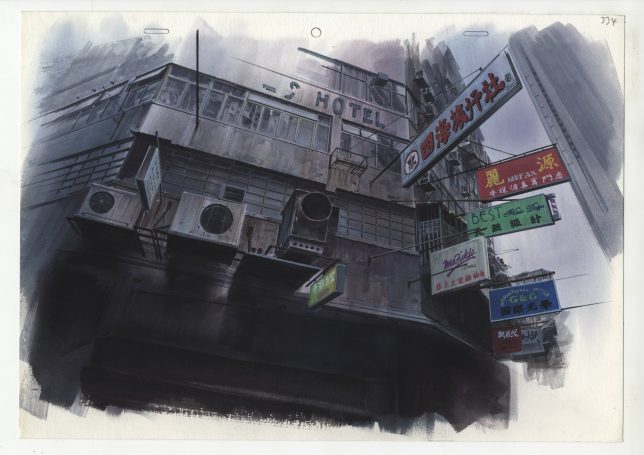

3) When shooting whole rooms, don’t get too wide

When I first started taking practice photos of architectural photography, I used the widest angle lens I could get my hands on to shoot entire rooms. My thinking was that with an ultra-wide lens, I could get more of the room in the frame. But more isn’t always better. I quickly noticed the high level of distortion towards the edges of the frame, especially in smaller rooms where the edges of the frame were at wide angles to the camera.

So, I experimented with different focal lengths and came to the conclusion that between 21mm and 28mm gives you the most practical balance between limited distortion and a wide enough frame to capture the character and presence of the scene. Ultra-wide lenses (i.e. 14 or 15mm) will make the sides of the frame look oddly stretched and off the horizontal plane, even when corrected in post-production.

If you’re in a situation where 21mm won’t capture enough of the scene, a panorama is always an option – which segues nicely into the next tip:

This was an extremely dark room, even with all the lights on. So, like the previous image, I stacked two shots: one exposed for the room, and one exposed for the windows, and combined them in Photoshop.

4) Try panoramas for ultra-wide shots

Set up your camera vertically on the tripod (which creates a taller pano). Then, making sure you adequately overlap the scene in each shot, do your best to make the camera rotate on a perfectly level, horizontal plane, with the pivot point being roughly where the lens meets the camera.

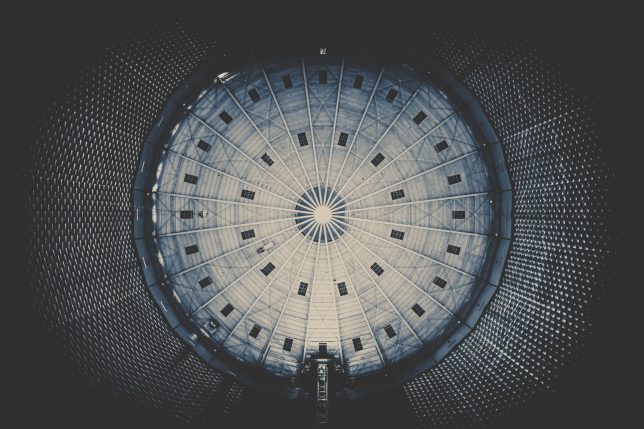

If the pivot point is too far forward (i.e. somewhere on the lens), or too far backward (i.e. on the body of the camera), the panorama will appear distorted. For example, in the picture below, the pivot point was on the body of the camera (behind the ideal spot where the lens meets the camera). As a result, the panorama has a weird sort of convex distortion.

This is a seven image panorama. See how artificially “rounded” the walls are? This will happen when shooting a panorama if your camera/lens are not properly situated on the tripod.

5) Whenever possible, try to shoot only one or two walls

Two wall shots typically give the viewer the most geometrically pleasant image to view. When three (or more) walls are introduced, the photograph can have a tendency to appear somewhat awkward-looking if you aren’t careful with the composition.

21mm focal length, f/11, ISO 100, 1/120th. One off-camera flash used.

The above shot is a generic two-wall scene, with the walls meeting at a standard 90 degree angle. The image below is the same room, except I backed up several feet to purposely include the third wall on the left edge of the frame.

The “third wall” on the left side of this shot creates an unnatural and visually-displeasing scene.

I don’t know about you, but to me, the photo above looks compositionally awkward and disorienting because of the third wall on the left. All of that said, just like the Rule of Thirds can occasionally be broken to make a photo work, sometimes getting three walls in the shot is okay – provided everything is geometrically aligned.

A properly-aligned three-wall shot. 21mm focal length, f/11, ISO 100, 1/200th.

6) Make sure your camera is perfectly level

Last, but definitely not least, you will want to make sure your camera isn’t tilted up or down, or tilted to the left or right. Doing so, even slightly, will require post-production cleanup. Here’s an example of what I’m talking about:

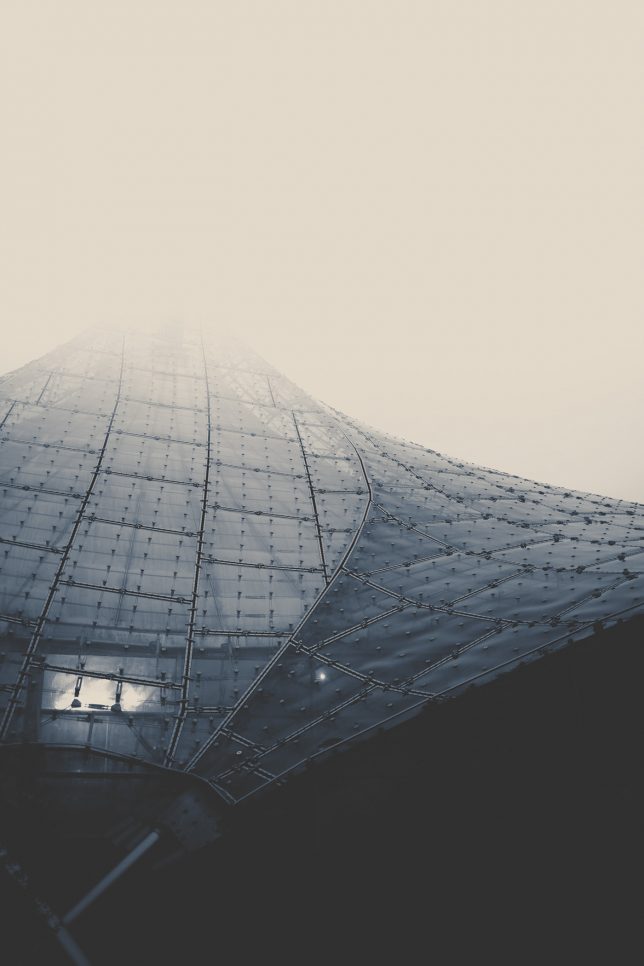

In this shot, the camera/lens were not level on the tripod. They were slightly slanted down towards the ground, creating the artificially slanted walls.

See how slanted the windows are? Clearly, this is not an accurate depiction of the room, it’s the result of the camera being tilted ever-so-slightly down. Now, see what a difference makes if we get the camera nice and level.

Camera/lens properly level on the tripod. 21mm focal length, f/8, ISO 100, 1/120th. No flash (this room had plenty of sunlight to illuminate it without artificial help).

Being level makes a HUGE difference. There are several ways to help you get the camera perfectly level when you compose your shot. Most cameras these days have a built-in level, so when you look into the viewfinder, there are lines across the focusing screen that will tilt when the camera tilts. When these lines are level, you know the camera is level.

You can also use a bubble level that slides onto the camera’s hot shoe. When the little bubble is centered, the camera is level. You can buy a hot shoe bubble level at any photography store for just a few bucks. I use a bubble level because they tend to be more accurate than the lines inside the viewfinder.

In this shot, I used Photoshop to remove the camera, lens, and tripod, which were all reflected in the mirror. Sometimes shooting into a mirror is inevitable, and when you do, cloning in Photoshop is a requirement.

Conclusion

As is the case with any type of photography, the most important aspect of getting the shot right is to take your time, and make sure your composition and exposure are exactly what you want. One good thing about architectural photography is that the composition and subject will never move (unless you move it), so there’s no need to rush the photograph.

The post 6 Helpful Tips for Doing Interior Architecture Photography by Jeb Buchman appeared first on Digital Photography School.

Digital Photography School

You must be logged in to post a comment.