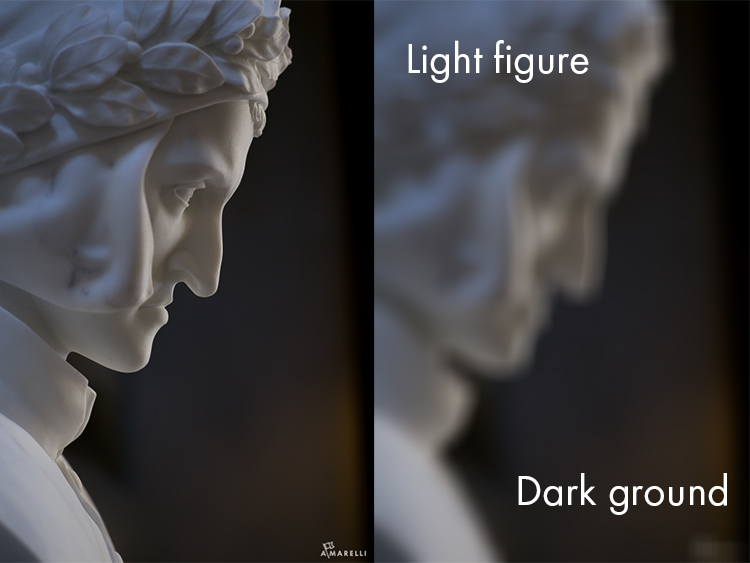

Light figure on a dark ground, Florence, Italy © Adam Marelli

What is figure to ground?

Why can you recognize an amazing photograph but struggle to produce one? Sure there are better cameras, advanced lighting techniques, and endless theories on composition, but very often the root of the problem lies in a simple concept that is often missed. In three words, we can sum up almost every cover of Vogue, National Geographic, and the New York Times – Figure to ground.

What is this term, what does it mean, and where does it come from? Figure to ground is one of the most important, and easily overlooked concepts, in photography. It’s not a rule, it’s not a law – it is a tool, and a very powerful tool at that. Once you learn it, it will become a part of every picture you take, no matter what type of camera you use.

If you were ever curious to see masterful use of figure to ground, try revisiting the photographers you already love like Steve McCurry, Richard Avedon, or Henri Cartier-Bresson. They all use it, some more elegantly than others. Figure to ground acts like an anchor in a photograph, holding the viewer’s eye inside the frame.

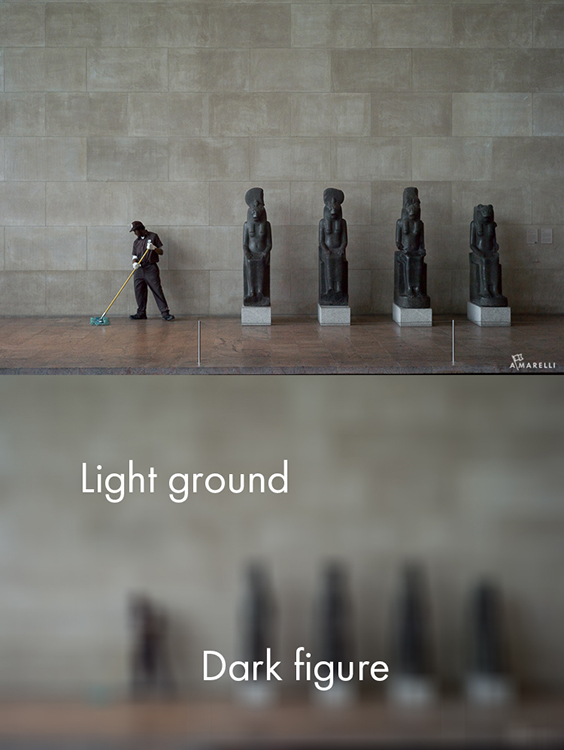

Dark figure on a light ground, Florence, Italy © Adam Marelli

It goes by many names

Figure to ground has a multitude of names; subject to background, figure separation, foreground to background, and the list goes on. To simplify, figure to ground is the most descriptive and easiest to say, which is why artists have favored it for centuries.

Light figure on dark ground, Berlin, Germany © Adam Marelli

A starting point

When it comes to describing visual tools in the written language, firm definitions are always a problem. Consider the following definition a starting point, not an immovable scientific definition.

Figure to ground is the visual relationship between objects and the space they occupy. We live in a 3D world, but your photographs are a 2D translation. When the third dimension of depth disappears, you end up with a problem that has plagued artists since they started scrawling on cave walls, how do you create a picture of the 3D world with only two dimensions?

Figure to ground allows your brain to determine shapes, sizes, distance and other optical illusions that exist in photography (it also applies to drawing, painting, and other 2D arts, but for this article the focus is on photography and how you can use it successfully).

Dark figure on a light ground. Berlin, Germany © Adam Marelli

Where did it come from?

The idea of figure to ground comes from drawing and painting. It forms the basic grammar of the visual language. Think about it, how can you see a shape on a piece of paper? It is visible because it is a black line on a white page. Seems obvious right, but what is that phenomenon called? It is called figure to ground. Imagine if we wrote in white ink on white paper – everything would be invisible.

The same thing applies to photographs. In order for your photograph to be legible, we must be able to see the object against the background. Artists have worked with this concept for centuries and developed elegant solutions to figure to ground as a deliberate, but subtle, technique for making pictures.

Light figure on a dark ground, Matera, Italy © Adam Marelli

How to practice it

The first step in practicing figure to ground is to condition your eye by looking at good examples. If you want to be a great photographer, study master painters and how they use figure to ground. You can do this on the internet, in a book, or at a museum. Pick the one that is easiest for you.

TECHNIQUE 1: The Book

Pick up a book on a famous Renaissance artist, like DaVinci, Raphael, or Michelangelo. Setting aside whether you like their work or not, the way to use art to your advantage is to master the tools of successful artists, and apply them with your own unique touch. Lay a piece of tracing paper over the page and be sure to cover the whole picture. Can you still see the subject? If yes, there is good figure to ground. If the subject seems to disappear into the background then no, the figure to ground is weak.

TECHNIQUE 2: The Museum

If you wear glasses, this will be even easier. Go to a museum and find a painting. Following DaVinci’s advice on viewing distance, stand three times the height of the painting away from it (example: if the painting is five feet tall, stand 15 feet away). Now squint at the painting until it is all blurry, or simply remove your glasses. Can you still make out the major shapes in the painting. If yes, there is good figure to ground. If the subject seems to disappear into the background then no, the figure to ground is weak.

Light figure on a dark ground. Kyoto, Japan © Adam Marelli-8

TECHNIQUE 3: The Computer

If you prefer to use technology, here is a technique you can do in Shotoshop. Pull a picture into Photoshop. Select Filter > Box Blur > set the pixels at 15 pts. You will end up with a blurry version of the picture. Can you still make out the major shapes in the painting? If yes, there is good figure to ground. If the subject seems to disappear into the background then no, the figure to ground is weak.

TECHNIQUE 4: Your Photography

Try any of the techniques above with your own photographs. If there is not strong figure to ground in your picture, play closer attention to the backgrounds when you shoot.

Camouflage

What if you never learn figure to ground, what will happen? Will it be impossible for you to ever make a good picture? No, of course not. But when you understand why some pictures work better than others, and what tools to use at the right time, you will enjoy photography much more. It relieves the anxiety of, “Will I get the shot?”. When you have a toolbox full of resources, it becomes easier to create consistently powerful pictures.

If you would like to know what the opposite of figure to ground is, look no further than camouflage. Camouflage is designed to obscure objects in space. It is the direct opposite of figure to ground. If the goal is to blend in, then use camouflage – if the goal is to pop out, use figure to ground. It is your choice.

Dark figure on a light ground. Matera, Italy © Adam Marelli

Tools are not rules

Photography is an artistic expression. It might be your break from everyday life, the pressures of work, or the hidden talent you want to explore. Whatever role photography plays for you, the idea to take away is that photography is not a rule book. BUT – and this is a big BUT, there are tools involved. You can use a tool the way it was intended and achieve amazing things, or you can spend your life using a chisel as a fork and wonder why eating is so painful.

Think of your photography like a toolbox; it might have a hammer, a chisel, a screwdriver and a wrench. You might use more than one tool at a time, and all tools will not be used for every job. Your role as the photographer is to know how to use each tool at the appropriate time to reach the desired effect. Otherwise you might end up hammering screws and painting nails.

Dark figure on a light ground. NYC, USA © Adam Marelli

Developing subtlety

Where do you go from here? Here’s an assignment that will be very helpful:

1. Find 20 examples of figure to ground in paintings

2. Find 20 examples of figure to ground in photography

3. Go take 10 pictures of light figures on a dark ground

4. Go take 10 pictures of dark figures on a light ground

Once you practice this enough it will become like a reflex. Please share your comments and images below.

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

tablet_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_tab-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78623” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

mobile_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_mob-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78158” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

The post How to Use Figure to Ground Art Theory in Photography by Adam Marelli appeared first on Digital Photography School.