[ By WebUrbanist in Architecture & Cities & Urbanism. ]

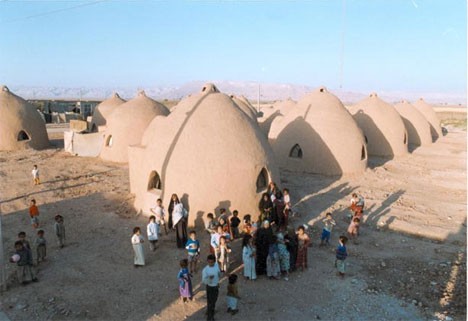

Former mayor of the world’s second-largest refugee camp, humanitarian Kilian Kleinschmidt notes that the average life of a refugee camp is 17 years, “a generation,” and these places need to be recognized as what they are: “cities of tomorrow,” not the temporary spaces we like to imagine. “In the Middle East, we were building camps: storage facilities for people. But the refugees were building a city,” Kleinschmidt told Dezeen in an interview. Short-term thinking on camp infrastructure leads to perpetually poor conditions, all based on myopic optimism regarding the intended lifespan of these places.

Many refugees may never be able return home, and that reality needs to be realized and incorporated into solutions. Treating their situation as temporary or reversible puts people into a kind of existential limbo; inhabitants of these interstitial places can neither return to their normal routines nor move forward with their lives.. On the one hand, assert experts like Kleinschmidt, planners need build up refugee camps to be durable and sufficient places in their own right. On the other, they also need to move refugee migrants toward countries and regions where they will end up virtuously integrated into struggling economies, including (though controversially): areas of nearby Europe with unused housing and high labor needs.

Beyond providing more thoroughly for essentials, Kleinschmidt sees additional opportunities to enable refugees with new technologies: “With a [3D-printing] Fab Lab people could produce anything they need – a house, a car, a bicycle, generating their own energy, whatever,” he said. Unfortunately, governmental bureaucracies and aid organizations are reluctant to push boundaries and try new approaches. More fundamentally: they frequently fail to recognize the need for robust solutions that help facilitate refugees who are themselves working hard to create real places for living.

“I think we have reached the dead end almost where the humanitarian agencies cannot cope with the crisis,” he said. “We’re doing humanitarian aid as we did 70 years ago after the second world war. Nothing has changed.” Kleinschmidt worked with the United Nations and their High Commission for Refugees for 25 years before starting an independent consultancy that continues to address humanitarian issues around the globe.

His previous senior roles included deputy humanitarian coordinator for Somalia, deputy special envoy for assistance to Pakistan, acting director for communities and minorities in the U.N. administration in Kosovo, executive secretary for the Migration and Refugee Initiative (MARRI) in the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe, and many field-based functions with U.N.H.C.R., U.N.D.P. and W.F.P. He worked extensively in Africa, Southeastern Europe, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

[ By WebUrbanist in Architecture & Cities & Urbanism. ]

[ WebUrbanist | Archives | Galleries | Privacy | TOS ]

You must be logged in to post a comment.