The post How to Simulate Long Exposure using Stacked Image Averaging appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Rick Ohnsman.

Silky water effects, streaked clouds, motion-smoothed with an ethereal look; long exposure photography seems to be in vogue as photographers discover the looks that can be created. There are multiple ways to achieve this. The most basic is to buy a standard neutral-density photography filter which cuts the light, allowing you to use long shutter speeds without overexposing your shot. You can achieve exposures minutes long, especially when using 10-stop ND filters like the Lee Big Stopper or even the 15-stop Super Stopper.

I recently did an article on an alternative way to make long exposure photos, “Try this DIY Neutral Density Filter for Long Exposure Photos.” I encourage you to read the piece and learn how a piece of welding glass can be a budget substitute for more expensive photographic ND filters.

This is the same location I used for some of the other shots in this article but taken when the river was much higher and faster. The biggest difference is that I used DIY welding glass ND filter to achieve this shot. See my other article for this technique.

This article teaches you a third method of making long-exposure images with no filter at all. Unlike the welding glass trick which pretty much requires your final image to be monochrome so as not to have to fight the heavy color cast, this works great in full color, with no filter at all, and no color cast present. It’s a great method to simulate long exposure.

The technique uses a stack of multiple images of the same scene then processed with a Photoshop process called Image Averaging. It’s really quite simple and has some advantages over traditional methods with ND filters.

Advantages over the traditional ND filter method

When doing traditional long exposure photography with an ND filter you will be making long exposures. (Duh!) There are a few challenges with this:

- If during the long exposure you bump the camera or things move in the shot you don’t want to be blurred, you will need to re-do the shot.

- Long exposures can often be several minutes in length. Double the time if you also enable in-camera noise reduction. If it takes 2-minutes to expose and another 2-minutes for the noise reduction to work, you will only be making a shot every 4-minutes. This can really slow down your work, and if the light changes during that time, you could miss it.

- With very dark ND filters, you won’t be able to see anything through the lens once the filter is in place. You will have to compose your shot, pre-focus, then mount the ND filter and make the image.

- Determining exposure will take some calculation. You’ll check exposure without the filter then use a calculation tool to determine the new shutter speed the ND filter requires. Often this will need some tweaking after you see your shot and…yup, another re-do will be needed.

- If back in editing you see the shots and wish you’d gone for longer or shorter shutter speeds to change the look, too bad. You’d have to go back and reshoot – if that is even possible.

In fairly bright sunlight, even with the ISO at 50 and aperture at f/22, 1/5th of a second was as slow a shutter speed attainable while maintaining proper exposure. This was with no filter.

The advantages of the Image Averaging method

The advantages of using the image stacking method are essentially the opposite of those things just stated above:

- You’ll be making multiple images rather than one long one. If one of the images in the group has a problem, you may be able to eliminate it and use the rest to still successfully create the effect.

- You can see what you’re doing! Not shooting with a dark filter means you’ll still be able to see, compose, use auto-focus, auto-exposure, and even image stabilization if you shoot handheld.

- No calculation! Without the addition of a dark filter, you eliminate this step.

- Adjust the length of your “simulated slow shutter” later in post-production. Want more or less blur? You can change your mind later.

- Are conditions too bright for a standard long exposure shot? Maybe you only own a 6-stop ND filter, and daytime conditions are too bright to let you get the length of exposure you’d like. You can combine both methods to simulate a longer exposure than possible with the ND filter alone.

- Are people in the shot you’d like to remove? Because they are likely to move during the multiple shots, when the averaging process takes place, they will vanish!

Make people disappear! Notice on the inset the people walking in the river, but on the completed shot, 15 images, each 1/5th of a second = 4 seconds simulated. They are gone.

Making the shots

Setting up and shooting the images you need for your image-averaged creation is much the same as any photography. Here are the factors and steps to keep in mind:

Composition still counts!

Because you introduce a long exposure blurred effect does not mean that you will have automatically created a good photo. Still consider how to carefully compose your image. Take into consideration that moving objects in the shot will blur and look simplified with less detail. Good long exposure shots often emphasize the contrast between static, non-moving objects (buildings, rocks, trees, etc.), and moving objects like clouds and water. Include both in your shot.

Shoot on a tripod

I mentioned you could do this handheld and, well…maybe you could. However, even with this technique, you will still want to shoot at the slowest shutter speed possible. That way, you won’t have to make too many shots for combining. Once you get much slower than 1/30th of a second (and faster than that if if you’ve just had coffee), handholding your camera is probably going to ruin your shots.

All Images ISO 50, f/22 . Top left – No filter – 20 images each 1/5 second = simulated total = 4 seconds. Top right – No filter – 35 images each 1/5 second = simulated total = 7 seconds. Bottom – 6-Stop ND filter – 15 images each 20 seconds = simulated total = 5 minutes.

How many shots?

This technique simulates long exposure by combining multiple shots. The simple formula is:

(# Shots) x (Shutter Speed of each shot) = Total simulated shutter speed effect (in seconds)

Let’s plug some numbers into that and see the result. Set your camera for the lowest ISO possible. I can get my Canon 6D down to ISO 50. Some cameras will have ISO 100 as the lowest. Use whatever you can. Set your aperture to the smallest aperture possible. Meter with those settings and see how long you can make each individual shot and have it properly exposed. Say we were able to do this in the shade: 1/4 second, f/22, ISO 50. To get a simulated shutter speed of one minute (60 seconds), we’d need to make 240 shots.

240 shots x 1/4 second (.25) = 60 seconds

That’s a little unwieldy, and stacking 240 shots in Photoshop may cause your computer to choke. So what to do? Perhaps you don’t have an ND filter in your bag, but you do have a circular polarizer. It will help reduce the light. You mount it and now find you’ve lost 2-stops. So your exposure can be 1 second, f/22, ISO 50. Plug that into the formula, and you get:

60 shots x 1 second = 60 seconds

If you’re shooting in lower light conditions, you may be able to get a slower shutter speed to start with. That will mean you can take fewer shots.

To make your job easier (and the computers as well), always try to get the slowest shutter speed you can for your shots. That will mean you can create the simulated long exposure with fewer shots.

Say you did have a 6-stop ND filter in your kit. You mount that, and now your settings are 16 seconds, f/22, ISO 50. Now, to get that simulated 1-minute exposure, you’d just need about four shots. Why not make 10 while you’re at it and you can simulate a 2.6 minute (160 seconds) exposure?

Had you done this traditionally, and had a 10-stop ND filter, you could take the unfiltered exposure down from 1/4 second, f/22, ISO 50 to 256 seconds (4.2 minutes), f/22, ISO 50. So, to get the same effect with a 6-stop ND filter as you could with a 10-stop by using image averaging, take 16 shots.

16 shots x 16 seconds each = 256 seconds (4.2 minutes)

35 images each 1/6 second combine to simulate a 6-second exposure. Shooting into the sun, it would probably be impossible to make a 6-second exposure without a filter.

Forget the math, make the shots!

If all that math made your head hurt (it did mine), here’s the simple way to get what you need so Photoshop can do its magic:

- Use a tripod. You don’t want to do all this and get shaky shots. That will waste all your work.

- Do what’s necessary to shoot with the slowest shutter speed you can get with the equipment you have. In the camera, that will usually mean setting the lowest ISO and smallest aperture.

- If you have a polarizer or ND filter, use those to get the shutter speed even slower if you can.

- Make lots of shots for each stacked image you will create. Depending on how slow you were able to get your shutter speed, a few dozen isn’t too many. You don’t have to use them all when you get into editing, but having more will allow a longer simulated effect.

Putting it all together

This recipe assumes you will be using Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop in combination. You don’t have to use Lightroom. You can get your individual images into a stack in Photoshop another way if you need to (though using LR is much easier). Using Photoshop, however, is mandatory. Also, to use the Smart Objects function described, you will need a version of Photoshop that is Version 14.2 or higher. Older versions of Photoshop won’t have this.

There are ways to do this with older versions in a more manual process. If you have an older version, you will need to do a little online research to learn that technique. I used the latest version of Photoshop at this writing (Photoshop CC 20.0.4).

Let’s look at this step-by-step process visually…

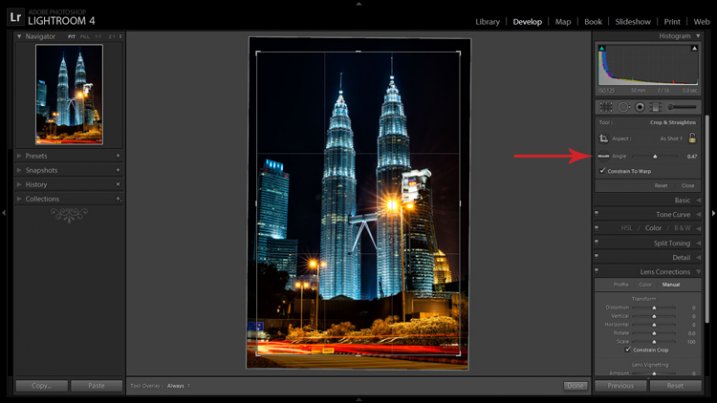

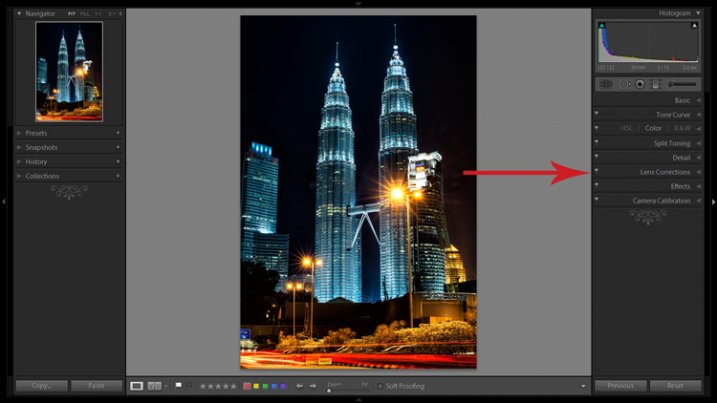

1. From Lightroom, select the sequence of images you will use. Edit the first one in the sequence to your liking. Then select all of them and use the Sync function so all have the same settings as the first.

2. With all selected, send the images from Lightroom to Photoshop by going to Photo->Edit In->Open as Layers in Photoshop. (Photoshop will open, and the images will appear as layers in a stack). If you have a lot of images to be opened and stacked, this can take a while. Let it work.

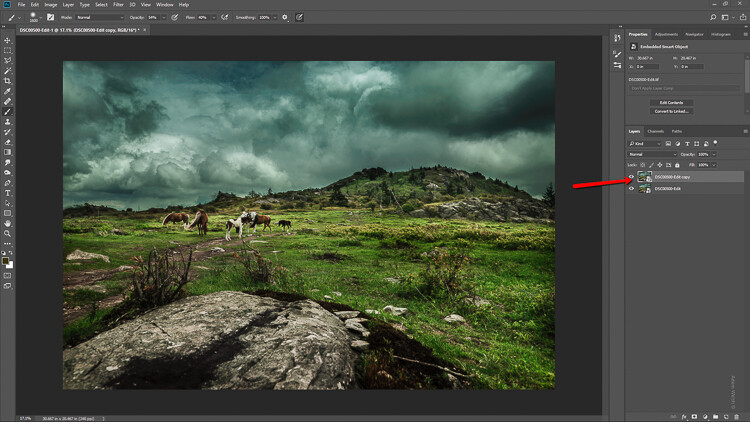

3. With all the layers selected, in the menu select Layer->Smart Object->Convert to Smart Object. This can take a while to do its work. Be patient.

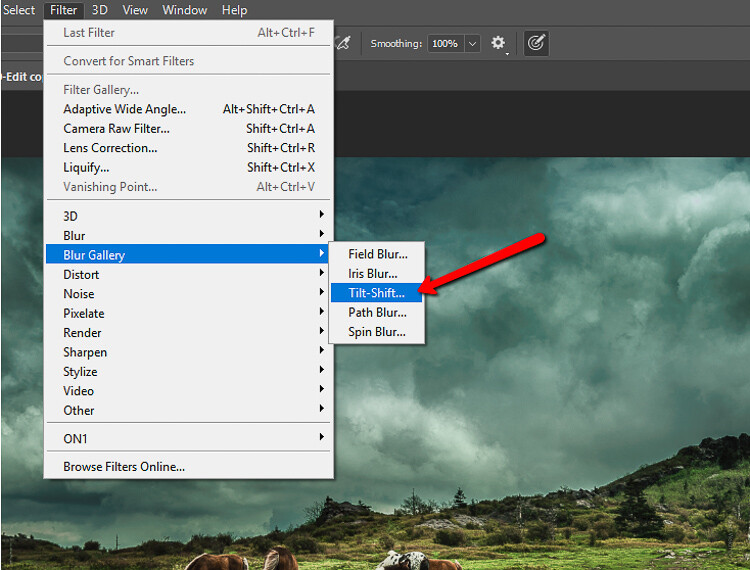

4. With the Smart Object layer selected, from the menu select Layer->Smart Objects->Stack Mode->Mean. This can also take a bit to work.

Wait for it…wait for it…and…

Presto! You will have a simulated long-exposure image made from your stack of shorter exposures. 20 images each at 3.2 seconds, f/22, ISO 50. No filter used. Simulated long exposure of 64 seconds.

The water in this section of the river was pretty calm anyway, but look at the before and after areas pointed out by the arrow where the original shots were 3.2 seconds vs the combined 20 shots x 3.2 seconds = a simulated 64 seconds.

5. To finish up, go to Layer->Flatten Image. Then File->Save As and save the finished image where you like. If you want to give the completed image some additional tweaking, you can do that with Photoshop or Lightroom as you would with any other image.

Remember…

That’s the magic! Here are a few things to remember for best results:

- Consider your composition. Look for a scene where you will have a combination of static objects that won’t move during the sequence and those that will. An image with both will be more compelling.

- Use a tripod. You can do this handheld if you must, but know that any camera movement will be translated as a blur in the final result.

- Do what you can to get as long a shutter speed with each image in the sequence as possible. Drop your ISO to the lowest setting, use a small aperture, and use polarizing filters or whatever ND filters you have. Longer exposures for each shot mean fewer images are needed to create a simulated long exposure.

- Overshoot. You don’t need to use all the images in a sequence if you decide you don’t want as much blur. However, if you don’t shoot enough, you might later wish you had them.

- As you work through the steps, some things can take a long time. Be patient and let your computer work. If the process crashes, it could be you don’t have enough computer resources and will have to settle for a smaller stack.

5 images, each 6 seconds = a simulated exposure of 30 seconds. No filter used.

10 images, each 1/4 second combine to give a 2.5-second simulated exposure. This can be a great technique to use for getting silky water effects when you don’t have an ND filter and only need a longer exposure of a few seconds.

Final thoughts

Is this a better method than using an actual ND filter? Like so many photographic things, the answer is probably…it depends. Maybe you don’t have a filter or have one with you. Perhaps you don’t need a really long exposure, but just one a little longer than you can get with a low ISO/small aperture combination such as when seeking blur on a waterfall. Maybe you need to vanish people and don’t want to make a single multi-minute shot for various reasons. Alternatively, perhaps you have an ND filter but need an even longer exposure than it can give you.

There are lots of reasons to add this How to Simulate Long Exposure using Stacked Image Averaging Technique to your bag of tricks. Give it a try, and I’m sure you’ll have fun. Share your images with us in the comments!

The post How to Simulate Long Exposure using Stacked Image Averaging appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Rick Ohnsman.

You must be logged in to post a comment.