The post Mastering Color Series – The Psychology and Evolution of the Color PURPLE and its use in Photography appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Megan Kennedy.

Purple has had a long history in visual arts. From prehistoric to modern artworks, purple has come to represent aspects of religion, royalty and status. In this article, we’ll look back on the history of the color purple, its evolution and its impact in the context of modern visual art.

The psychology of purple

In the traditional color wheel used by artists, violet and purple are placed between red and blue. Purple takes up the space closer to red, between crimson and violet. Violet is positioned closer to blue. Despite this, both violet and purple are often placed under the one heading of purple, sharing psychological associations.

As an intermediary between red and blue, purple tempers the extremes of both. Like blue, purple has a soothing effect, cultivating introspection and calm. Like red, purple also generates a visual vibration, stimulating creativity and passion. Lighter purples are considered light-hearted. Darker shades of purple are associated with wisdom and intellect.

Over history, the limited resources and arduous processes needed to obtain rich purples made it an expensive luxury. For this reason, the color purple came to be associated with status, royalty and wealth. Perhaps due to it’s uncommon and distinctive presence in nature, purple has also been attributed to exoticism, mystery, and magic.

In Christian tradition, purple is used during lent to signify mourning and majesty, anticipating the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Hinduism associates purple with a oneness with God, peace, and wisdom. In China, purple represents spiritual awareness as well as physical and mental healing. Japanese cultures view purple as the color of privilege, wealth, and Japanese aristocracy. In Africa, purple is a symbol of status and wealth, whereas, in Brazil, purple can indicate mourning or death.

The evolution of the color purple

Hematite and manganese

Used by Neolithic artists in the form of sticks, or ground and mixed with fat as a paint, hematite and manganese are the oldest pigments used for purple coloring in art. Dated between 16,000 and 25,000 BC, early artists used purple to draw and paint figures and the outlines of their hands on the walls of sites like Pech Merle cave in France. Manganese is still used today by some indigenous Australians as a traditional pigment for coloring the skin during rituals.

Han purple

Despite it’s name, Han purple has been found to occur well before the Han dynasty in China. Created by melting silica with copper and barium at high temperatures, Han purple first appeared on glass beads found at burial sites. The pigment was later used in wall paintings, ceramics, and sculptures, including the terracotta warriors in the tomb of Emperor Qin Shihuangdi in Xi’an. The use of Han purple peaked in the Qin and Han dynasties (221 BC to 220 AD), declining during the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD).

Han purple can fade and decompose over time, particularly when in contact with acids or heat. However, the unique light-absorbing and emitting properties of the pigment generates powerful rays of light in the near-infrared range when exposed to an LED flashlight. This means that even faint traces of the pigment (invisible to the naked eye) can be viewed by conservators and scientists evaluating Han purple and its properties and history.

Tyrian purple

Ranging from a reddish to bluish purple, Tyrian purple became the most renowned shade of purple in history. Citizens of Sidon and Tyre, two cities on the coast of Ancient Phoenicia, (present-day Lebanon), were producing purple dye sourced from the mucous secretions of certain sea snails by the 15th century BC. The process for extracting the color from the snails was both unfortunate for the snail and protracted for the dye-maker as more than 10,000 snails were needed to dye a single cloak.

According to an article in The New York Times, the extricated snails were “…boiled for days in giant lead vats, producing a terrible odor. The snails, though, aren’t purple to begin with. The craftsmen were harvesting chemical precursors from the snails that, through heat and light, were transformed into the valuable dye”.

Tyrian purple was extremely pricey, and purple-dyed textiles became the color of emperors, generals, nobles, politicians, priests and magistrates throughout the Mediterranean.

Although it was used predominantly for dying textiles, Tyrian purple was also used for painting. Tyrian purple has been chemically detected in the Saffron Gatherers, a late bronze age fresco in the Aegean Island of Santorini.

Purple in the middle ages

During the middle ages, artists created purple pigments by mixing red and blue mediums together. For blues, artists sourced blue azurite or lapis-lazuli. For reds, red ochres, cinnabar, madder or minium were used. Artists also mixed woad or indigo dye for blues and cochineal dye for reds. Different mixtures resulted in different intensities and shades. However, many of these materials were prone to fading and many paintings with purple have dulled or changed in color. Jan Gossaert’s painting of a young princess is an example of this – the pattern on the garments of the sitter, now seen as blue, were originally purple in color.

Mauve

In 1856, 18-year-old British chemistry student, William Henry Perkin, was working on a cure for malaria. During his experiments, he encountered an intriguing residue, the first synthetic aniline dye. Perkin realized the compound could be used to dye fabrics. He soon patented the dye and manufactured it under the name aniline purple and (confusingly) Tyrian purple. The color’s name was later changed to mauve in 1859, reflecting the French name for the purple mallow flower. Chemists called the dye compound mauveine.

Mauve quickly became fashionable. Queen Victoria wore a silk gown dyed with mauveine to the Royal Exhibition of 1862. Perkin developed an industrial process, built a factory, and produced the dye in large quantities. His efforts made purple accessible to anyone, not just the wealthy. However, due to dye’s propensity to fade, the success of mauve faded too, replaced by other synthetic dyes by 1873.

Cobalt violet and manganese violet

The first truly violet pigment was cobalt violet, developed in 1859 by Salvetat. Ranging from deep to pale shades of violet with either a pink or blue hue, the first cobalt violets were composed of cobalt arsenate. The highly toxic compound is now rarely used, replaced today by cobalt ammonium phosphate, cobalt lithium phosphate, and cobalt phosphate.

The only truly lightfast violet pigment with relatively strong color saturation, all alternative light-stable violet pigments are duller in hue. Although in use today, the high price, weak coloring power and toxicity of cobalt violet have limited the pigment’s application.

Also known as permanent violet, Nuremberg violet or mineral violet, manganese violet is believed to have first been discovered by E. Leykauf in 1868. More affordable and less toxic than its predecessor, manganese violet became an economical alternative to cobalt violet in the 1890s and remains in use today.

Love Symbol #2

In 2017, the Pantone Color Institute announced a new shade of purple in honor of the singer Prince. The hue, dubbed Love Symbol #2, is a blue-based purple inspired by Prince’s adoption of the color throughout his career. Laurie Pressman, Vice President of the Pantone Color Institute said: “long associated with the purple family, Love Symbol #2 enables Prince’s unique purple shade to be consistently replicated [while maintaining] the same iconic status as the man himself”.

“Why this particular purple?” asks Pressman. “We are not sure of the exact reason, however, what we do know is that the language of this unique new purple, Love Symbol #2 conveys an aura of mystery, intrigue, and unconventionality, a color that stands apart from all others, something Prince, a performer of distinctive style, certainly did”.

Purple in visual arts

Ancient art to realism

The use of manganese and hematite to create purple pigments dates back at to at least 25,000 years BC. Evidence of purple in art has been found at sites such as the remote East Kalimantan province of Borneo and Neolithic sites in France. Much later, during the early stages of the church, variations of purple garments marked the hierarchies of Christian officials (mirroring the practices of pagan traditions). In medieval art, pages of the bible and gospel manuscripts were written in gold lettering on parchment dyed Tyrian purple. In Byzantine-style painting, figures of importance were depicted in purple robes.

Renaissance art saw portrayals of angels and the Virgin Mary garbed in purple. Because Jesus was said to have been clothed in purple by Roman soldiers during the events leading up to his crucifixion, purple also signified suffering, sacrifice, and majesty. The Assumption of the Virgin by Palma Vecchio features Mary dressed in a long purple gown. In Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, God is dressed in a subtle lilac shift.

Purple featured in post-renaissance movements such as baroque and rococo art, academic art and realism. In 1789, French rococo artist, Antoine Callet, depicted Louis XVI in his royal costume, which included a luxuriant panel of purple material. Painted between 1880 and 1890, Wladyslaw Czachorski’s Lady in a Lilac Dress portrays a woman in an opulent lilac gown. The Shepherdess by academic artist William-Adolphe Bouguereau features a cool, purple backdrop, rhyming with the shepherdesses’ own garments. However, as seen in Jean Francois Millet’s The Angelus, realist artists broke away from the depiction of purple as a status symbol, instead using subtle variations of the hue to reflect the harshness of middle and lower class society.

Pre-raphaelite to abstract art

Combining cobalt blue with madder, pre-raphaelite artists like John William Waterhouse painted women in rich purple garb. As seen in Monet’s Grainstack (Sunset), Waterloo Bridge, Blurred Sun and Water Lilies (1919), impressionist painters used purple to delineate both shadow and detail. Purple also played a significant role in post-impressionist art, as seen in A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat.

The symbolism movement saw purple used in increasingly varied applications. In paintings such as Death and Life by Gustav Klimt and The Cyclops by Odilon Redon, purple is used to highlight detail and depth. Fauvism then pushed purple to shocking brilliance. Henri Matisse’s Woman with a Hat sees purple mashed together with a range of colors, creating life and vibrancy. In Woman in a Purple Coat, Matisse exploits purple as a bold separation of subject and environment. Mirroring impressionism, Andre Derain painted shadowy purples, as seen in Charing Cross Bridge, London. And Jean Puy used fluid purples to illustrate Strolling Through Pine Woods.

As seen in Puberty by expressionist Edvard Munch, purple was distorted or exaggerated in ways that matched expressionism’s often hostile or alienated depiction of the modern world. Examples of purple in cubist art include Picasso’s Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle and Claude, Son of Picasso. Abstraction, devoid of recognizable figurative imagery, used degrees of purple to evoke emotional responses in the viewer. Composition 8 (1923) by Vasily Kandinsky, Untitled (1957) by Franz Kline, Black Iris VI by Georgia O’Keeffe and Purple, White and Red 1953 by Mark Rothko are examples of purple’s application in abstract art.

Purple in contemporary art

As color technology evolved, purple became increasingly available to artists. In contemporary art, purple signifies both modernity and history, reflecting the social and cultural connotations of the color through time. Vaporwave, both a musical genre and artistic movement, incorporated the use of purple heavily in its internet-based aesthetic. Constructed of neon and tar, Dan Alva’s You Zig I Zag has roots in pop culture. Monira Al Qadiri’s sculpture of an iridescent blue and purple oil drill illustrates the industrial processes of the oil industry. And Lori Hersberger makes use of purple in his sculptures and installations, exploring light and the transformative properties of color.

Purple in photography

Although it’s less available than other colors in the urban and natural landscape, purple is a favorite for many photographers. Because of its historically rare beauty, purple is often used to convey the surreal, the modern and the artificial. David LaChapelle utilizes purple to create striking contrasts signaling commodification and modernity. Marilyn Mugot documents the neon-purple landscapes of urban China at night, while Maggie West utilizes the otherworldly properties of purple in her bodies of work. Purple also has a strong presence in the experimental photography of Ellen Carey and in the aura photography of Christina Lonsdale.

Interestingly, colour outside our visible spectrum can be explored photographically. Consisting of longer wavelengths than those of visible light, near-infrared (as opposed to far-infrared, which is in the thermal-imaging territory) is generally invisible to the human eye. However, with infrared film, an infrared filter or a converted camera, photographers can capture near-infrared wavelengths, which, when emitted from different types of foliage, are often rendered as ethereal purple tones. Near-infrared photography can be mimicked in post-production, creating beautifully alien landscapes out of earthly forms.

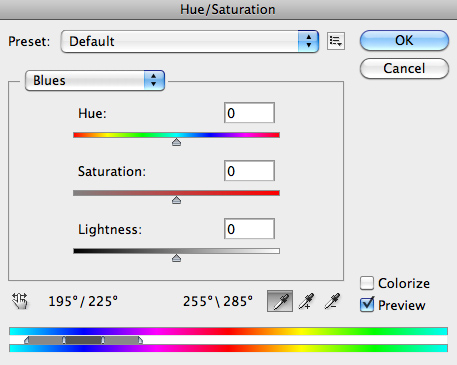

Purple can also manifest as unwanted purple fringing. Most visible as a purple-colored fringe in the dark edges of a subject adjacent to illumination, purple fringing is usually caused by axial chromatic aberration. Because axial chromatic aberration occurs at its most severe at shorter wavelengths, fringing is rendered in violet. Methods for reducing purple fringing include shooting with a UV filter, avoiding overexposing highlights and not shooting with a wide-open lens in high contrast situations. Purple fringing can also be corrected in post-production.

Conclusion

From its origins in ancient art to its use in contemporary visual practice, purple reflects the visual complexities of life. As a combination of blue and red, purple absorbs attributes from each, inspiring clashes of calm and passion, stillness and visual movement. Due to its rarity in nature, purple has been associated with mystery and exoticism.

Historically difficult to obtain, purple has become a symbol of status, wealth and majesty. Purple’s role in religion has been linked to spirituality and mysticism. And purple’s momentum is believed to inspire both creativity and reflection. With such a diversity in meaning and visual scope, purple’s versatility connects with a wide range of audiences. Evoking emotions based in art and life, purple is a color of intricacy and depth.

We’d love to see your images that make use of the color purple. Feel free to share them in the comments below.

The post Mastering Color Series – The Psychology and Evolution of the Color PURPLE and its use in Photography appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Megan Kennedy.

Digital Photography School

You must be logged in to post a comment.