The post How to Prepare Images For Publication – Part Two appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Herb Paynter.

In part one of this series, I presented the reasons why images printed in magazines and publications can appear lackluster, dark, and dull rather than detailed and vibrant as when printed on an inkjet printer. In this follow-up article, I address the unique requirements and limitations of printing presses and some ways to produce rich and detailed images in print.

Fine Tuning the Process for Print

Paper surfaces

The depth and detail that a press can reproduce in the darkest (shadow) portions of an image are limited by several print-related factors, with the paper grade (quality) being the biggest factor. Printing papers come in various grades, textures, and shades of white.

White is a relative term, and newspapers are a prime example. Newsprint isn’t actually pure white and the ink printed on it never appears black.

Printing inks

Newspaper inks are nearly in a liquid state as opposed to other forms of print. The tack level (stickiness) of these inks must remain very low since the newsprint paper composition is quite soft. Full-bodied inks printed at high speed would tear the paper apart. Instead of appearing as black ink on white paper, newspapers appear more like charcoal colored ink on light gray paper. This factor alone dismisses the visual contrast in pictures. Newsprint absorbs ink like a paper towel, which is why pictures in the newspaper lack contrast, punch and depth.

Magazine paper surfaces

Publication (magazine) presses fair much better. However, they still have limitations. Paper grades for publications are still lower quality than those of brochures and coffee table books because of the economy of the project. Most publication stocks are made from recycled papers in which many of the whitening agents and glossy coatings used in higher grade papers are absent. This results in less reflective surfaces and varying shades of off-white colors. While the recycled paper is good news for the environment, it’s bad news for print quality.

The challenge

High-speed presses must also reduce the tack level of their inks to keep these papers flowing through the presses. When the tack level goes down, so does the opacity of the inks, and when the tack level of translucent inks is reduced, the contrast in the images (and image detail) is also reduced. You can see where this is headed…

The creative solution

Thus the challenge is to maintain as much apparent contrast in each image as possible under less than ideal circumstances. Here is where the creative magic of contrast “compensation” enters the picture. Prior to the era of digital editing, this creative level of tonal manipulation was simply out of reach. While adjusting the overall contrast (white, middle, and black points) of printed images has always been possible, serious contour shaping was not. But within current digital image editing software, the entire internal range of tones can be tuned and cajoled with great precision. Success simply takes a clear understanding of the limitations and a good knowledge of the tools in the digital tool chest.

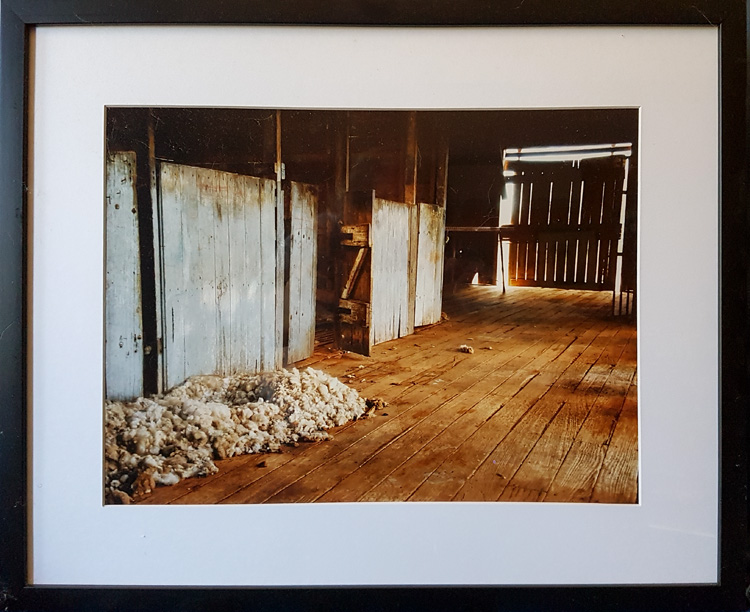

The Sun backlit the subjects in this photo causing the darker areas to hide significant detail. If sent to press without compensating adjustments, the printed results would have looked even darker and important detail would have been lost.

Pictured here are the settings that produced the civil war reenactment photo above. Information contained in the middle tones and shadow tones was recovered by powerful tonal adjustments available in each of the four software applications. Very similar settings produced very similar results. The panels (from left to right) include Adobe Camera Raw, Adobe Lightroom, On1 Photo RAW, and Alien Skin X4.5. Camera Raw and Lightroom produced identical results from identical settings for obvious reasons, while the development engineers from On1 and Alien Skin used unique routines and algorithms in their software to affect very similar results.

The secret to success in adjusting the internal contrast of an image is in developing a distinct visual difference between the whites and highlights and the shadows and black tones. This is best addressed within the six major tonal sliders provided by most RAW editing software (Lightroom, Camera Raw, On1 Photo RAW and Alien Skin’s Xposure X4.5) best address this.

Don’t let the term RAW scare you away. These editors can open and process just about all image file types (RAW, JPEG, TIFF, etc.). Each of these packages provides very similar tonal area adjustments (Exposure, Contrast, Highlights, Shadows, Whites, and Blacks) though each maintains a slightly different range for each. Additional controls to fine tune the tonal values include the Tone Curve adjustments of Highlights, Lights, Darks, and Shadows.

The beauty of all these controls is the fact that they are nonlinear, meaning they can be adjusted in any order and at any time during (and during follow-up) editing sessions. Using these editing packages, truly non-non-destructive image editing can be made to RAW, TIFF and JPEG image files.

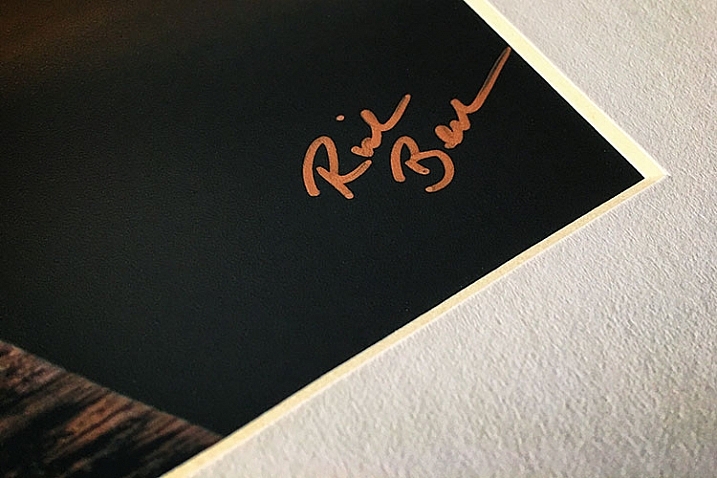

Backlighting and a black cat provided a serious challenge in this image. These adjustments were needed even if the picture was not going to press.

Three aspects of tonal controls

Familiarize yourself with these three general aspects of tonal controls to prepare your photos specifically for the printing press.

One

Since camera image sensors capture very little shadow detail, digital images require significant internal contrast adjustments to the lower portion of the tonal scale.

Shadow tones of each image are the most challenging areas to print cleanly on press. Therefore, you must create a sharp distinction between the darkest darks (Black slider) and the three-quarter tones (Shadow slider).

Use the Exposure slider in conjunction with the Blacks slider to bring out all the detail in the darkest portion of the image. Reference the histogram to gauge the actual pixels that will print darkest.

Two

Lighten the middle tones and accent the difference between the quarter tones and the highlights.

Use the Curves tool to affect the middle tones while adjusting the Shadows slider and Highlight Slider to define the middle tones further.

Three

Reference the histogram again to monitor the lightest tones (White slider). White is a misnomer in the labeling of this slider as its influence is on the extreme highlight tones. Draw a distinction between the light tones and absolute white by using the Highlights slider and the White slider.

The Exposure slider and the Contrast slider play an important part in this tonal ballet. Choreograph these controls to achieve the best balance of internal tones and check your progress by occasionally tapping the “P” key to preview the composite effects of all your adjustments against the original image.

Seemingly lost detail in the darker areas was completely recovered by some severe adjustments to individual tonal areas throughout the tonal range. The image was recovered with only the use of the sliders shown. No further editing (dodging, burning, etc.) was required.

This article is hardly an exhaustive explanation of how to prepare images for publication inasmuch as it does not address the critical issues of color, sharpening, resolution, etc. But it will get you started on the most critical issues of tone sculpturing images for reproduction. In every example shown, ONLY global adjustments to the seven sliders was required to bring full life back into lackluster photos. The most critical aspect of post-production involves an image’s internal tonality.

Shape each image’s internal contrast specifically for the press and paper being printed. If you don’t, the printed image will probably hide shadow detail, lose their “snap” in the highlights, and produce muddy middle tones. Slight but deliberate accenting of the tone curve will produce significantly better images in print.

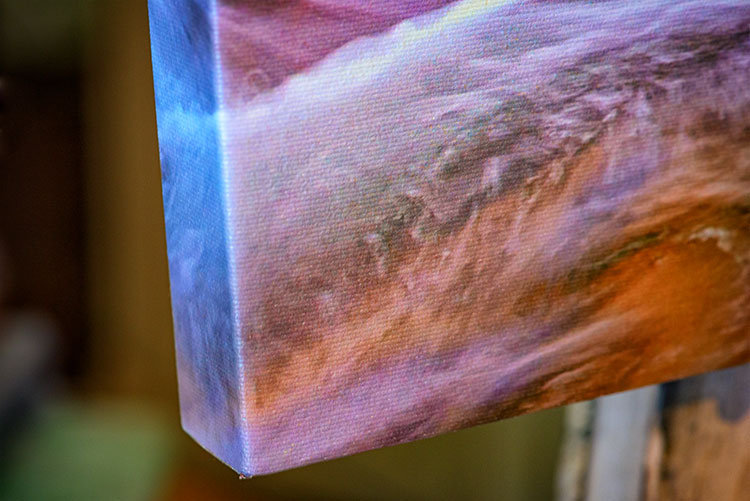

Working on images in these RAW Interpreter software applications provides amazing latitude in recovering both shadow and highlight detail. This example shows how On1 Photo RAW found significant detail in what appeared to be blown out highlights of a JPEG image.

Chasing light

At the core of the issue is light.

Everything about photography concerns light, and that includes viewing photos in print.

The reason images appear more vibrant and colorful on a monitor is because the background “white” is projected light, not paper. Images printed on paper will ALWAYS appear less vibrant. Paper is only as white as the light reflecting from it. The darker the paper and the dimmer the reflecting light, the less bright the picture appears. Images in print will never look as good as images on your monitor simply because reflected light cannot compete with projected light.

Conclusion

Preparing images to print correctly is a serious challenge, but one that delivers an amazing result. If you want to test your image editing skills, it doesn’t get more challenging than this. The reward for all your print-editing efforts will last a whole lot longer than a post on the Internet and will be seen by thousands (if not millions) more than a print hanging in a gallery. People collect well-produced publications and display them for others to see.

Virtually all images deserve thoughtful preparation before presentation. The camera can’t evaluate tonality balance by human standards. Learning the reproduction habits and limitations of different devices and understanding how to best compensate for each will pay serious visual dividends.

Of course, the final challenge in preparing images for publication is converting the color mode from RGB to CMYK. Check with your publication about this matter before you arbitrarily choose CMYK from the Image/Mode menu. There are a number of workflows that publications use to produce their final files for the printer. I suggest you leave the color conversion decision up to the magazine’s production staff. The conversion process is a complex issue that deserves much more attention than I’m addressing in this series.

Please feel free to comment and question what you’ve just read. Life is a collaborative effort, and we’re all learning.

The post How to Prepare Images For Publication – Part Two appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Herb Paynter.

You must be logged in to post a comment.