So you are out shooting and you want to capture the full scene in front of you – all the way from what is directly in front of you to the background way off in the distance. You know you need a really large depth of field, and you know what you need to do to get it.

You reach for the camera’s aperture control and crank it down all the way to f/22 (or f/32 if your lens allows). That will maximize your depth of field and have your picture looking sharp from front to back.

Or will it?

What is Diffraction?

There is a phenomena in photography called diffraction that has an adverse effect on your pictures, and sets in when you use smaller apertures. What is diffraction? Let me explain.

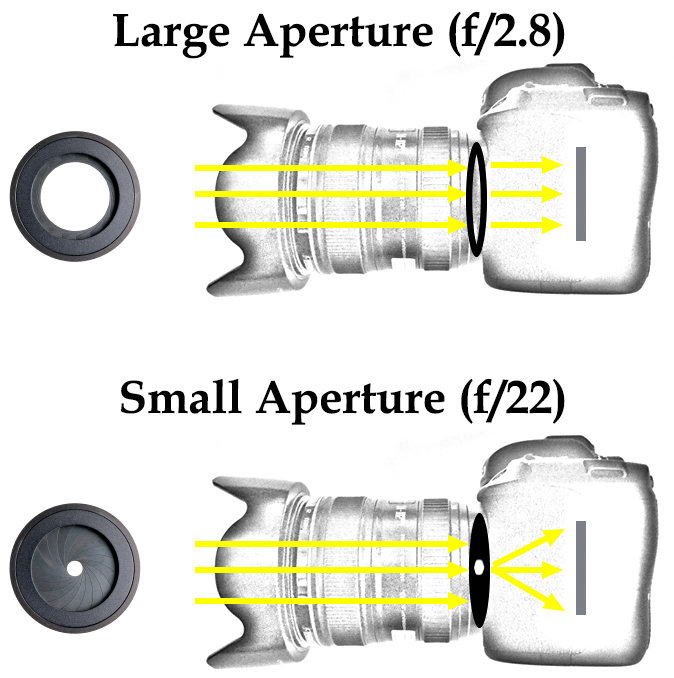

As you are probably aware, the aperture of a lens is the opening in the rear part of the lens that lets light into the camera. The body of the lens consists of optical elements that direct light toward the rear of the lens. When you use a large aperture, light freely moves through the optical elements and then through the aperture. When the aperture is very small, however, essentially the light has to bend to make its way through the aperture. That bending of light causes the waves to interfere with each other. The following graphic illustrates how this works:

What’s the result of this to your photography? In a word: softness.

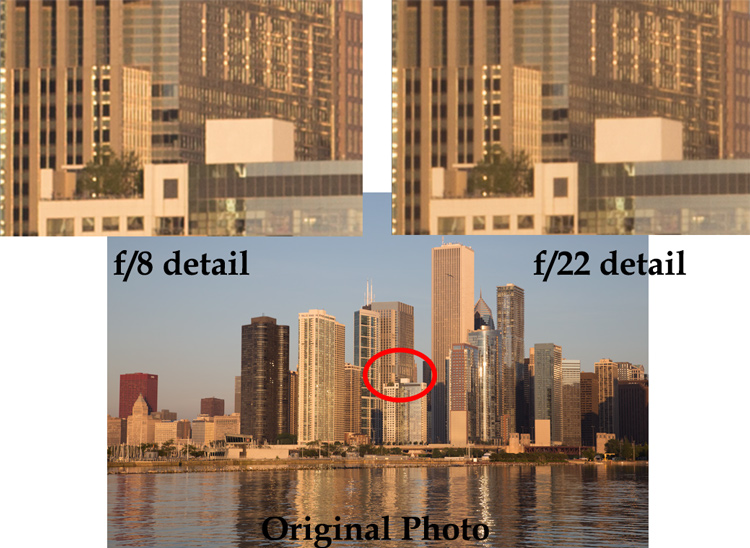

A picture shot at f/22 will not be quite as sharp as one shot with an aperture that is a bit larger. Here is an example of detail from two photos, which are identical except that one was shot at f/8 and the other at f/22:

You can probably see that the f/8 detail is sharper than the f/22 detail.

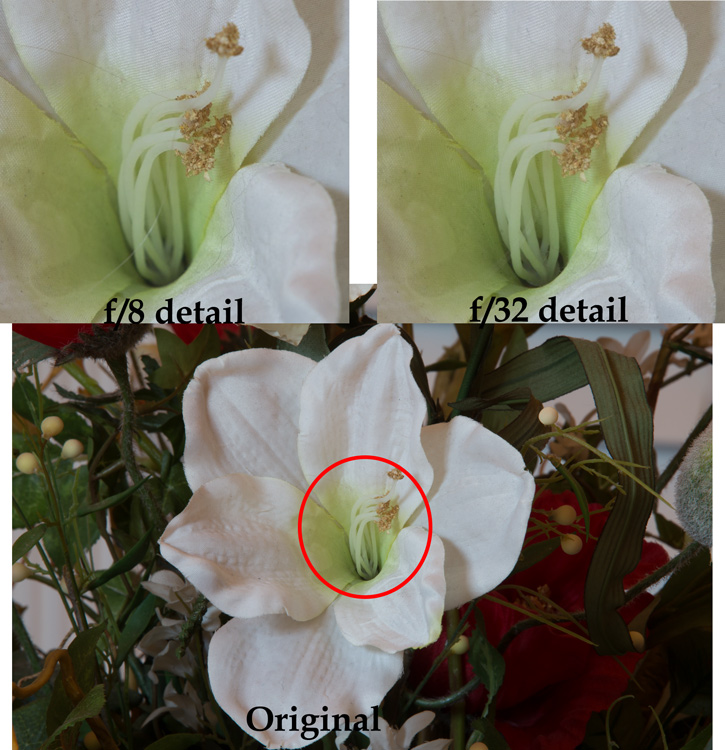

The example above was shot outdoors with a 24-105 mm f/4 lens (my favorite). To see this application in other contexts, I also created another example, this time shooting indoors with a 70-200 mm f/2.8 lens with a minimum aperture of f/32.

Again, the f/8 detail is sharper than that shot with the smallest aperture.

By looking at these examples, you can see that diffraction is not just theory, it has real affect on your photos.

Using the Sharpest Aperture

Okay, so now you see that diffraction is a real phenomenon, and you want to avoid it. What is the smallest aperture you should use? And what is the best aperture setting? Unfortunately, there is no one perfect answer. It depends on the lens. As a result, you should test your lens(es) to determine the aperture (or range of apertures) at which they work best (also known as the lens’ sweet spot).

To do so, just take the exact same picture at each aperture setting (in 1-stop increments). Be sure to use a tripod so your picture is exactly the same. In addition, make sure you are increasing (making longer) your shutter speed by an equal amount every time you change your aperture so that your exposure stays the same. After you have taken the pictures, load them onto your computer, zoom-in on each, and compare.

If you don’t want to test your lens and just want a quick rule of thumb for avoiding the effects of diffraction, generally avoid using an aperture smaller than f/11 or f/16. Most experts consider this range something of a maximum. In addition, the sharpest aperture on most lenses will be about f/5.6 – f/8, or about 1-2 stops smaller than its wide open aperture setting. When possible, default to using an aperture in this range.

Maximizing Depth of Field with Larger Apertures

You may find yourself wondering how to get a large depth of field without using a very small aperture. Keep in mind that you don’t always need to use the smallest aperture that your lens offers, to get a sufficient depth of field. If you are shooting outdoors, which is generally where you will want a small aperture and maximum depth of field, you should become acquainted with the subject of hyperfocal distance.

Despite its complex-sounding name, hyperfocal distance is just a measure of how close you can focus and still keep the background of your image acceptably sharp. You don’t necessarily need to use the smallest aperture possible, particularly when you are shooting wide-angle. For example, if you are using a full-frame camera with a 20mm lens, even using an aperture of f/8 will keep everything sharp from 5.5 feet in front of you, all the way to infinity!

This shows that you don’t always need to use an aperture like f/22. Get acquainted with hyperfocal distance (or keep a hyperfocal distance chart handy) to see how large you can make your aperture, yet still maximize depth of field.

Focus Stacking

Sometimes, however, you need to break out the heavy artillery and make sure everything – from what is right in front of you all the way to infinity – is in focus. To do that, use a technique called focus stacking.

To focus stack what you do is, take multiple pictures of the exact same thing at your lens’s sharpest aperture setting. Again, you should test your lenses to see what the sharpest setting is for each lens, but if you don’t know it will usually be in the range of f/5.6 – f/8.0. Set your lens to manual focus, and set the focus point on the closest part of the image (nearest part you want in sharp focus). Take the first shot, then repeat the process, gradually setting the focus point further and further away with each shot, until you are focused at infinity. Usually 3-5 shots will cover the entire range of the scene.

When you get your photos in your computer, you will combine the photos in Photoshop to create one file using the sharpest parts of each picture. There are a few different ways to do this:

- Automatic: Use the Photomerge function to load your photos into Photoshop (File > Automate > Photomerge) and combine the images, making sure that the box to “blend images together” is checked. Photoshop will combine the images into one file and (usually) use the sharpest portions of each image.

- Partial: You can also load the images as separate layers to one file in Photoshop, align your layers (Edit > Auto-Align Layers), and then have Photoshop automatically blend the layers (Edit > Auto-Blend).

- Manually: Finally, you can do the process manually if you want complete control over it. Load the images as layers to the same file align the layers. To blend the photos, add a layer mask to the top layer (Layer > Layer Mask > Reveal All) and use a black brush to mask away everything except the sharpest point of that picture. Then merge down that layer (Layer > Merge Down) and repeat the process for each layer. This method will obviously take more time than the first two options above.

At the end of this process, you will have combined the layers such that the sharpest portion of each one is showing. The photo will be 100% sharp from front to back – with no effects of diffraction.

Application to Your Photography

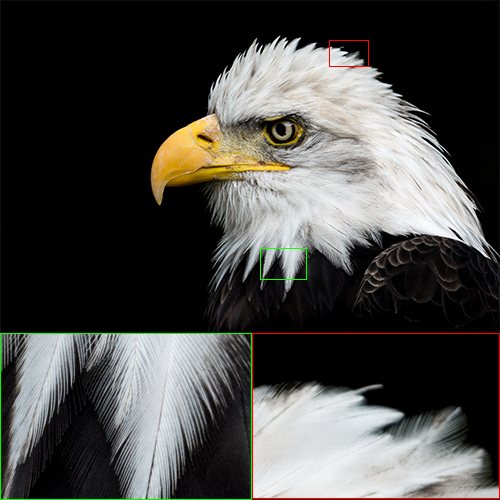

You should be aware of diffraction, but don’t let it scare you away from using the aperture that you need. In particular, there is still a place for shooting with very small apertures. The effects of diffraction – while real – are not that great, and keep in mind that the examples set forth above showing the effects of diffraction were zoomed way in. If we look at the original pictures, can you tell which one was shot at the smaller aperture?

Can you see any diffraction here? In the top row, the picture to the left was shot at f/22 and the one to the right was shot at f/8. In the bottom row, the picture to the left was shot at f/8 and the one to the right was shot at f/32.

Can you see the diffraction in the images above? I can’t.

Worrying about diffraction should be reserved for those times you are dead set on absolute maximum image quality, or you know you are going to display a large version of the picture. Otherwise, you can still shoot with small apertures and you will likely not notice the difference. In other words, there is still a place for f/22 in this world.

However, on those occasions where it does matter, use a slightly larger aperture. Know your lens’ sweet spot and use that setting. Be familiar with the hyperfocal distance involved and see if you can keep the entire picture sharp at the larger aperture. Where you cannot, use focus stacking, this will ensure the sharpest pictures possible.

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

tablet_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_tab-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78623” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

mobile_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_mob-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78158” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

The post Maximizing Depth of Field Without Diffraction by Jim Hamel appeared first on Digital Photography School.

You must be logged in to post a comment.