There is an unnervingly common trait among photographers, image makers, picture people, etc. Sometimes we forget that the reason we have access to such awesome gear and techniques, is because those who came before us in our trade figured them out, practiced them, advance them, and then left us a legacy of knowledge. The further we go back through the history of photography, the more prevalent this apathy becomes. What do you have to learn from someone who used a camera less advanced than a garage door opener? Well, as it turns out, we stand to learn a lot. Maybe not from a technological standpoint, but rather in a more intangible way that’s more difficult to appreciate, and easy to miss.

There is an unnervingly common trait among photographers, image makers, picture people, etc. Sometimes we forget that the reason we have access to such awesome gear and techniques, is because those who came before us in our trade figured them out, practiced them, advance them, and then left us a legacy of knowledge. The further we go back through the history of photography, the more prevalent this apathy becomes. What do you have to learn from someone who used a camera less advanced than a garage door opener? Well, as it turns out, we stand to learn a lot. Maybe not from a technological standpoint, but rather in a more intangible way that’s more difficult to appreciate, and easy to miss.

This is not to say that you can’t improve your photography from studying the methods of some of the masters. Their gear was varied and less advanced, but that only makes their work more extraordinary, and their skill even more humbling.

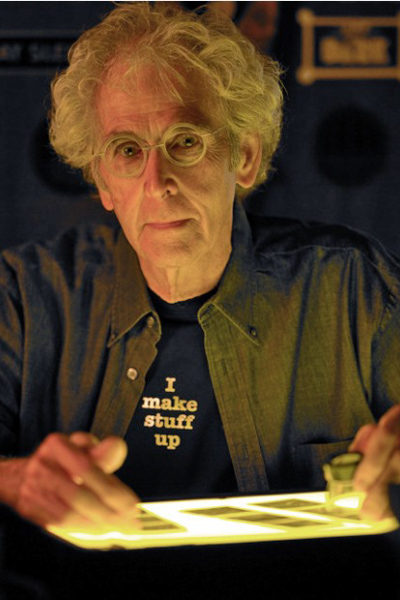

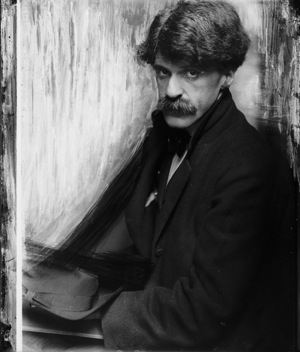

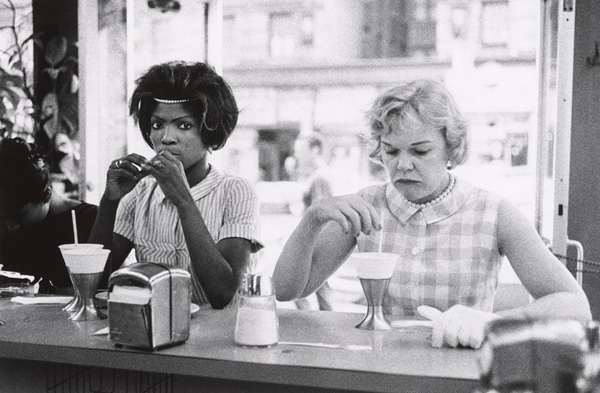

Henri Cartier-Bresson

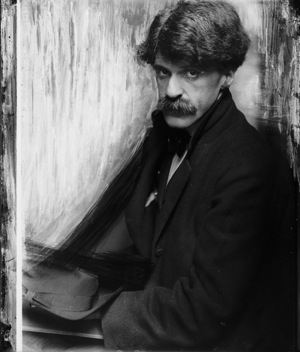

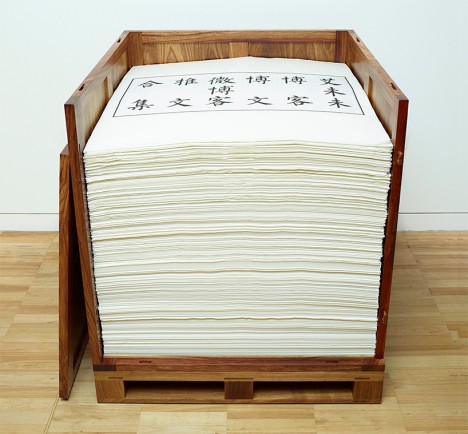

Image by Gertrude Käsebier

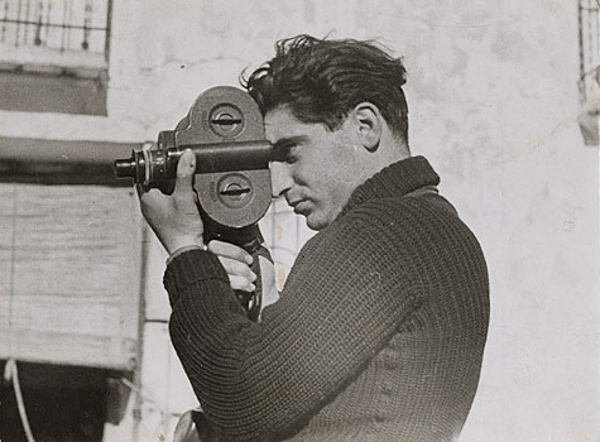

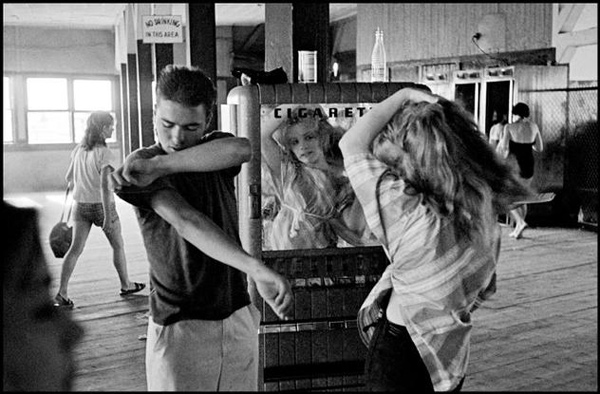

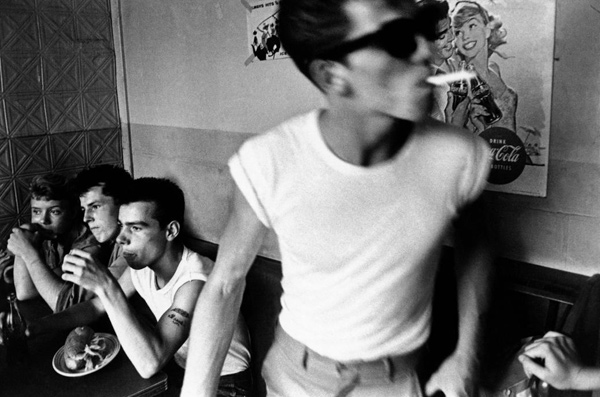

Even if the name doesn’t ring some little bell in your memory, chances are you most likely have viewed his work at some point. He was literally the inventor of the photojournalistic style… let that sink in for a minute or three. Before Cartier-Bresson, proper street photography as we know it and “still life reportage” as he called it was not a well practiced, or validated form of photography.

Born into a relatively well placed upper-class French family in 1908, Cartier-Bresson, like so many well known photographers, didn’t start out intending to be such. Painting was his major pursuit before picking up a camera. That all changed in 1931 when he set his eyes upon a photograph made by Hungarian photographer Martin Munkacsi. It was an image of three young boys in the surf of a lake in Africa. Cartier-Bresson said that he “couldn’t believe such a thing could be caught with a camera” and that he “suddenly understood that a photograph could fix eternity in an instant.” The photograph drove him to relinquish painting, and start making photographs. He was thoroughly a recorder of the spontaneity of human experience. There is much you can learn from Henri Cartier-Bresson to improve all aspects of your photo making.

Lessons you can learn from Henri Cartier-Bresson:

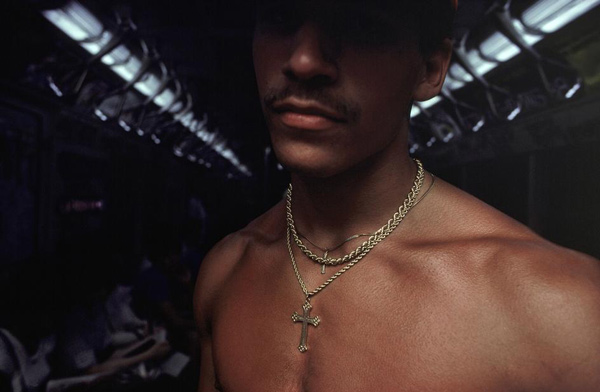

Strive to be invisible

When you’re working as a photographer it doesn’t take long to understand that humans tend to drastically change once they realize they are being photographed. Their mannerisms, expressions, and appearances all become noticeably different. Conspicuousness steals away realism very quickly if you are not careful. Cartier-Bresson understood this and moulded himself into somewhat of a photographic ninja. He shot with relatively small cameras, usually Leica 35mm Rangefinders. You have to understand that most photographers of his time were using larger format cameras which practically screamed “Hey, I’m making a photograph of you!!!” Anonymity allowed him to capture the essence of any scene in a way that was raw and unobtrusive.

Cartier-Bresson went so far as to conceal all the shiny surfaces of his gear with black paint to further decrease his footprint as a photographer. You might not want to go that far, but it will help you to capture better images if you blend into your surroundings. Plan for your sessions in a practical way. Don’t take more gear than you need, and keep a low profile. Try to wait until you’re ready to make an exposure before you raise your camera. Practice using your camera’s controls and memorize their placement. Also, avoid using a flash if it will likely interfere with your subject. Cartier-Bresson supposedly never used a flash for his images as he saw them as impolite and distracting. Photography, especially photojournalism, depends on the earnest capture of life in all its beauty, and regrettably, its occasional misery. Try to keep it real, literally.

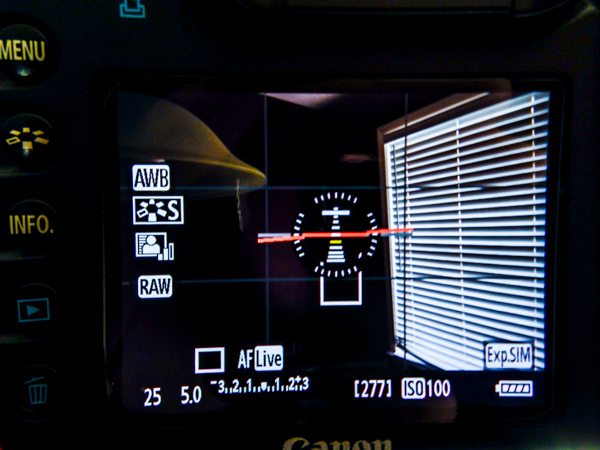

Compose in camera

I know, I know. You’ve probably heard this before, and are most likely tired of having that phrase hurled at you. I feel your pain. I would always roll my eyes any time a seasoned photographer or well intentioned writer would talk about the importance of getting things right in-camera. Let’s be real here. It’s so easy to crop an image on the computer instead of using the camera’s viewfinder. It’s so much more convenient to salvage a less than correctly exposed image than to think through your aperture and shutter combinations.

Post-processing photographs is a wonderful thing. Completely changing a photograph, however, is not always ideal. Cartier-Bresson was absolutely anti photo manipulation and believed any photograph should be cropped in the viewfinder before it was captured. Nearly all of his photographs were printed full-frame and even included about one millimeter of the unexposed negative so that his finished prints sported a thin black border to further prove the absence of cropping.

Any image is only as good as the ingredients put into its making. So try to put the best possible ingredients into your work so that your finished product will be something you will be proud to display and say “I made this”.

Focus as much on the art as the science

What we do as photographers would have been considered magic in an earlier time. Even at the basic level it is an amazing science. We record light that is completely unique and fleeting. You will never make the exact same photograph twice. The science of image making is an essential part of our creative process, but it must never be viewed as the only part.

Surprisingly, Cartier-Bresson expressed, on multiple occasions, his almost complete lack of interest in the more technical portion of making photographs. The developing and printing of his negatives, actions so carefully controlled and guarded by most serious photographers of the time, were valid only to him in the cases where they allowed more effective expression of his vision. He saw the camera as a tool, and development and printing as merely a means to a much anticipated end. He said “people think far too much about techniques and not enough about seeing”.

You can lose your direction during the of making an image. Sometimes we let technical perfectionism overshadow our initial vision. Thorough knowledge of your gear is essential to grow as a photographer. However, like Cartier-Bresson tells us, don’t allow yourself to become so focused on your tools that you forget your craft.

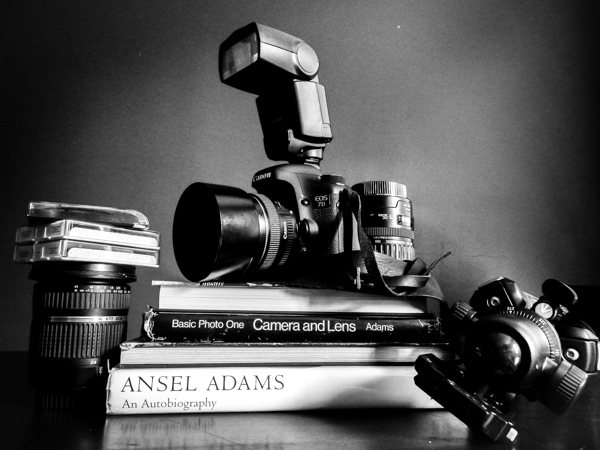

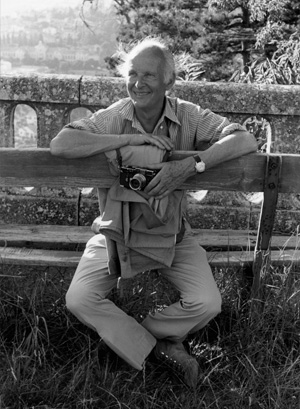

Alfred Stieglitz

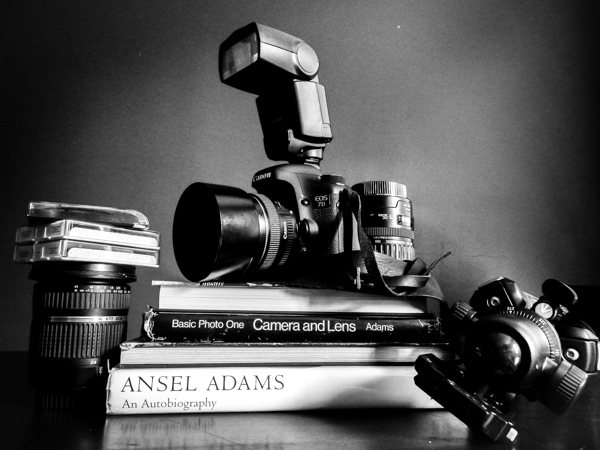

Alfred Stieglitz was born into this world on January 1, 1864 and left it on July 13, 1946. Anything else that I can tell you about the impact of man’s life upon the world of photography and creative art will fall unbelievably short of the full measure of gratitude we owe him as photographers. That’s not hyperbole. Before Stieglitz, photography was not considered a form of artistic expression. There were no real schools of photography, and it certainly was not considered high art on the level of painting and sculpture. Stieglitz gave artists an outlet to show their work to the public, and was the catalyst that helped begin the careers of many celebrated artists including the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, and the legendary photographs of the great Ansel Adams. Stieglitz was always open to new techniques and innovative thinking towards art.

His work is removed from our time by nearly a century, and many of the technical mechanisms he used are now obsolete. Still, there is much insight to be gained from Alfred Stieglitz, and his contributions. We can learn from his approach to the art world as a whole, to better ourselves as photographers.

Lessons you can learn from Alfred Stieglitz:

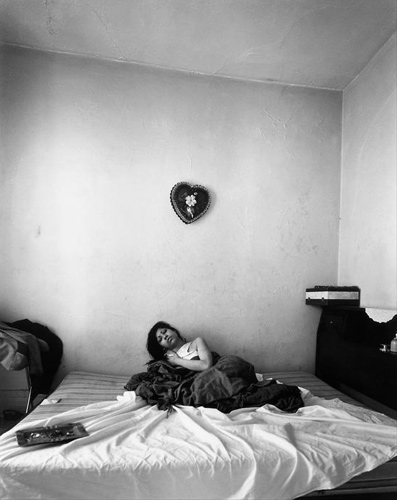

Express yourself when you can

Stieglitz created a series of images called “Equivalents”. It is a collection of photographs that show a variety of different cloud formations. Each image was a self-reflection of the thoughts, emotions, and experiences that he was feeling at the time the frame was exposed. That made each image unique to only him. He was the only person who truly understood how he felt during each release of the shutter. So go out and photograph something that makes you happy. Share it with others if you want, or just keep it for yourself. Go and make photos of something that is only beautiful, or meaningful to you. The act in itself is very freeing.

This spot has special meaning only to me. I made this photo for myself and no one else.

You might be thinking “I express myself with all my work”, but really think about it for a moment. Do you ever make a photograph and immediately consider how it might be accepted or rejected by other people? Do you sometimes share an image that you personally think is outstanding but no one else seems to care about? We have all done it more often than we might comfortably admit.

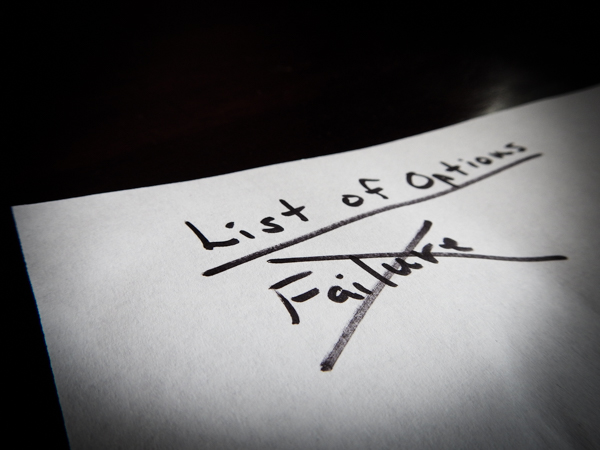

Break the rules if you want

Simply put, any photograph that has ever been produced, resulted from of a combination of the following variables: size of aperture, shutter speed, depth of field, focal length, image receptor sensitivity and composition (film, digital sensor, ect) and that’s all. The key to making a great image is putting all those pieces together in such a way that they convert what was only visible within your own mind, into a photograph. Those are the only iron clad rules in photography. In the end it’s you who make the choices and operate the camera.

Don’t be afraid to think outside the box!

Some really great work has resulted from stepping outside the mainstream. There are many stunning images that completely ignore the rule of thirds, leading lines, horizons, and so forth. Never completely cast aside guidelines, but don’t convince yourself that you are permanently tied to them either. Learning, and practicing, the tested and proven building blocks of strong photography will help you greatly. Just remember that ground breaking work often arises from the bending of rules.

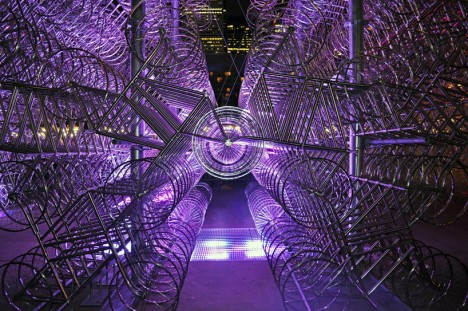

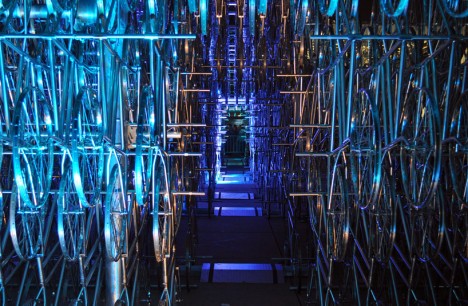

Look for inspiration everywhere

Stieglitz promoted all art forms. He opened galleries to display the works of painters, sculptors, and of course photographers. He didn’t limit himself to only photography, or painting or to works fashioned from stone and clay. Instead, he drank it all in. He recognized that it was all tangled together and intertwined.

As photographers we are able to almost instantly project what sometimes takes other artists days or weeks, or even months to create. However, this relative ease of creation can gradually place blinders on our creative thinking. We can reach a point when we only look at other photographs for inspiration. That kind of thinking limits our scope as artists. This mindset is especially dangerous for new photographers and can lead to frustration, disappointment and even worse, emulation that festers into plagiarism.

Don’t let yourself have artistic tunnel vision. Begin to look for inspiration everywhere to fuel your photography. Black and white sketches, paintings, wood carvings, architecture, kids finger-painting – everything has the potential to give you a smack of creativity that you can mould into photographic inspiration. The truth is that you really never know what will inspire you.

Please share your questions and comments below. Have you heard of these two masters before? Have they influenced your photography?

The post Cartier-Bresson and Stieglitz – Study the Masters of Photography to Become a Better Photographer by Adam Welch appeared first on Digital Photography School.

Digital Photography School

You must be logged in to post a comment.