During my career in photography, I’ve continued to evolve, both my shooting and editing styles, to achieve the results I wanted. Several years ago, while working with film editors on a cinema project, I came across a concept that I decided to apply to my own photography, and I have to say, it has improved my final images a great deal. Let me explain about using flat picture styles.

When Hollywood studios film a movie using a digital cinema camera, many times the camera will be set to record what is known as Log Gamma. This is similar to the picture styles that we DSLR and camera users have come to know and love. But while picture styles or picture controls are for the most part intended to provide a finished look, Log Gamma does just the opposite. A video file shot using Log Gamma will be very flat, with little contrast and color saturation. The purpose of shooting video this way, is so that it retains as much information as possible about the range of tones in the image, so the colorists who work on the video later can bring out that detail, and create a visual look to the film. This process is called color grading.

As I began to understand what the colorists were doing, I adjusted my workflow to allow me to take advantage of the same concepts. I find that by using a flat, low contrast, low saturation picture style, when I process the RAW file I can bring out better detail and contrast, and avoid clipping in the highlights and shadows.

Choosing a Flat Picture Style

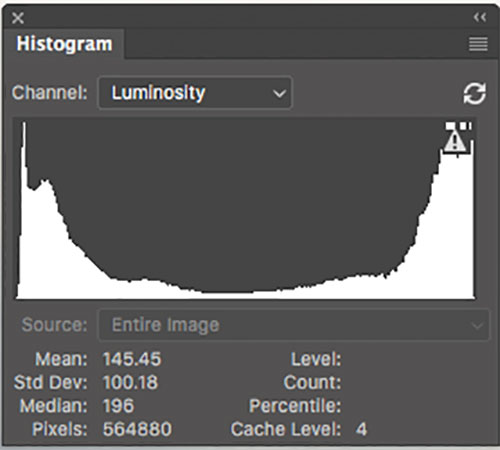

A flat or neutral picture style will give you an image with the least contrast, maintaining better highlight and shadow detail. This allows you to bring out those details in processing. The histogram on your camera, and later in Photoshop or Lightroom, allows you to see where your highlight and shadow tones fall, to avoid clipping.

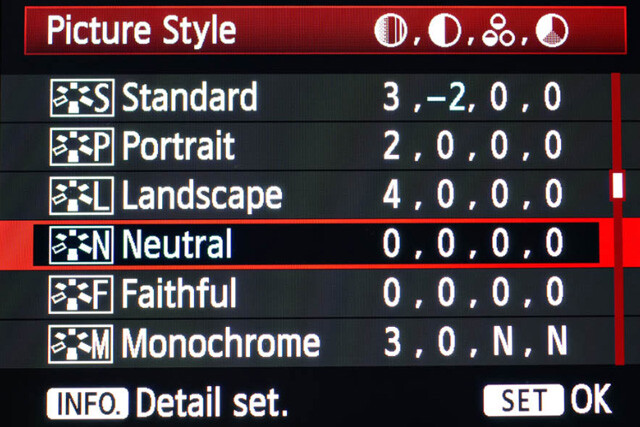

I had been shooting RAW for some time, but have left the Picture Style set to Standard or Landscape, for the most part. Once I saw this technique, I decided to change my picture style on my camera to Neutral (for Canon cameras) or Flat (on newer Nikons).

Canon Picture Style

The reason is that the histogram shown on the back of the camera, as well as the image preview, reflect the selected picture style. The result is that if the picture style selected is a more contrasty one, such as Landscape, the histogram will reflect that, and may indicate clipping of highlights or shadows, especially in a contrasty scene.

This histogram shows clipped highlights, meaning detail is lost in the brightest areas of the image.

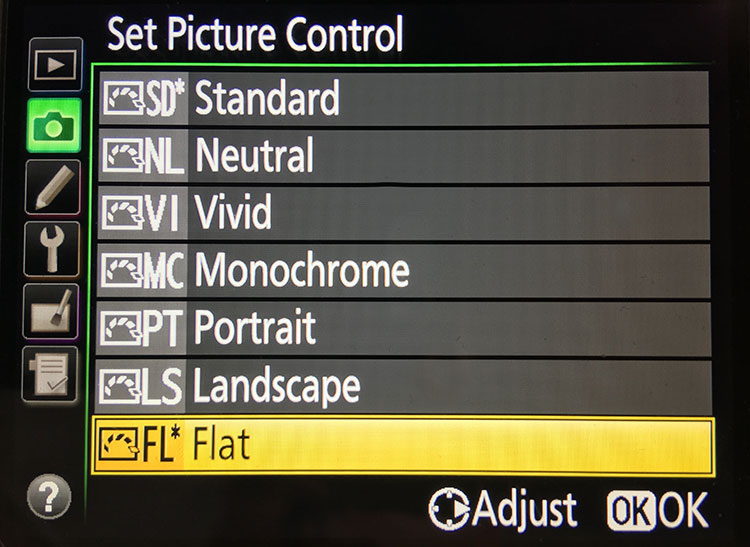

On my Nikon D810, I use the Flat picture control, because it is the best choice for capturing the full range of tones in the scene, and those tones are reflected on the histogram on the back of the camera when I review the shots. This is important because I need an accurate indication of where the highlights and shadows in a scene fall in my histogram.

Nikon 810 Flat Picture Control

Nikon picture control – if you do not have Flat, choose Neutral or Faithful

The histogram on your camera is a graphed indication of where the pixels in your image fall in relation to highlights and shadows. The left edge represents blacks, the mid-left represents shadows, the middle is midtones, the mid-right is highlights, and the far right is whites. While not all cameras have a Flat picture control or style, most have a Neutral or Faithful picture style or control, that works similarly. Also, most cameras give you the ability to edit the picture styles, so you can turn down the contrast if you like, ensuring that you capture more highlight and shadow detail, and reducing the chances of clipping highlights or shadows.

When you clip highlights, objects in the scene that are clipped will show as pure white with no detail. When shadows are clipped, objects in those areas will show as pure black in the scene, also with no detail. When viewing the histogram, if the squiggly lines that make up the graph are pushed up against either the left or the right side, that is called clipping. When that happens, you are losing detail in the shadows if it’s pushed against the left, and in the highlights if the graph is pushed against the right. By reducing the contrast in the picture style, you’ll reduce the chances of losing detail in the scene.

Shooting RAW, and knowing I’ll be making adjustments in post, it doesn’t really matter what picture style I use, because I can change that when processing the RAW file. But it’s essential to be able to see an accurate histogram on my camera, to ensure I’ve captured as much tonal range as possible.

Processing the RAW File

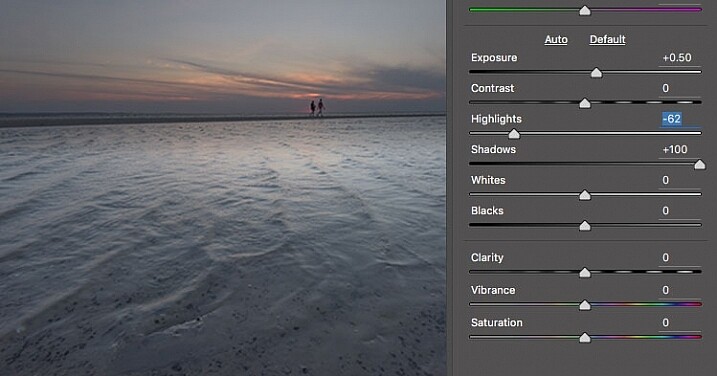

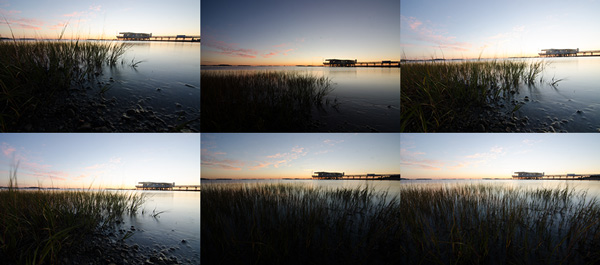

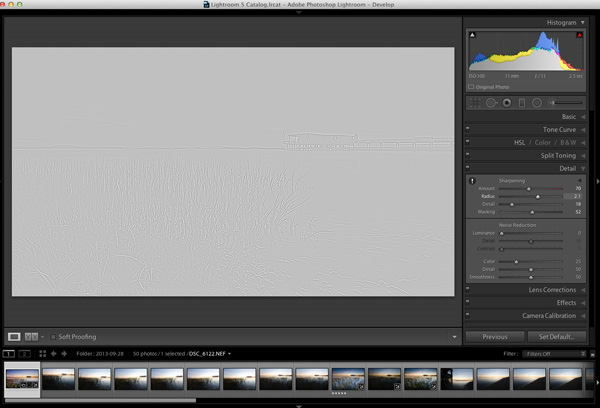

This image was shot using the Flat picture control, and then the highlight and shadow sliders in Adobe Camera RAW were adjusted to further reduce contrast.

Once I begin processing the RAW file, I’ll do even more, if necessary, to flatten the image and compress the range of tones within the histogram. This includes using the Highlights and Shadows sliders in Adobe Camera RAW to bring out details on both ends of the histogram. You can watch the histogram change in Adobe Camera Raw or Lightroom as you do so, to be sure you don’t go too far. If the highlights begin to look muddy, you’ve gone too far. By the same token, if the shadows start to look washed out, that’s probably too far as well. You want to maintain detail in each, but not lose the depth of tone completely. It’s important to note that this adjustment will vary for different images, depending on where the highlights and shadows fall in the images.

In addition to adjusting the highlights, shadows, and contrast here, I will use the Dehaze slider, Lens Correction, and Spot Removal brush in Adobe Camera RAW. If you prefer, you can use the Vibrance, Saturation, and Adjustment Brush to complete the image in Adobe Camera RAW or Lightroom, but my preference is to work in Photoshop. There I can use a Layers workflow along with masking and Adjustment Layers and with various plugins, to achieve my final image.

Building Up Color and Contrast

Using Adjustment Layers in Photoshop, I built up the color saturation and contrast to achieve the final image.

Once I have the image at the desired level of flatness, I then go about building up color saturation and contrast, or in Hollywood terms, color grading my image. After bringing the image into Photoshop, there are a number of ways you can go about this. The first is to use adjustment layers so that you can continually adjust each layer as desired, until you flatten the image for your final output. In addition, if you’re making an adjustment that you only want to apply in certain areas, you can use layer masks to hide or reveal it as desired.

Many of these adjustments will be to personal taste. I personally prefer my images to have punchy color and contrast. So a set of adjustment layers I might use would be Vibrance, Exposure, Hue/Saturation, Curves, and Exposure. The flexibility of using adjustment layers allows me to direct adjustments where I need them, rather than being forced to make them globally.

This is the same image, but I used Nik Color Efex Pro to achieve the final image instead of adjustment layers.

If adjustment layers aren’t your thing, perhaps using a plugin such as Google’s Nik Efex Pro. It’s now available at no cost, and is a software package I highly recommend. I’ve created several presets in Color Efex Pro, and will also use Viveza and its control points to further adjust my image. For landscapes, in Color Efex I have created a preset using Brilliance/Warmth, Pro Contrast, Skylight Filter, Detail Extractor, and Vignette:Lens, that I find to be pleasing for a majority of my landscape images. Depending on the image, I will tweak these settings to meet my vision.

Summing Up

On the left is the image with its tones flattened and desaturated, using a Flat picture control and adjusting highlights and shadows as needed. On the right is the image fully processed building contrast and color saturation.

By starting with a flattened file, you give yourself room in the range of tones to build contrast and saturation, without clipping highlights, shadows, or any of the color channels. While shooting with a more finished picture style may look more pleasing on the camera’s LCD screen, or upon import into Lightroom or Photoshop, the contrast has already been adjusted to give it a pleasing look. Any adjustments to Saturation or color may result in a file that at the very least looks overcooked, and at worst, shows evidence of clipping highlights, shadows, or color channels.

On the right is the image with the flat picture style, while the left has been “color graded” in Photoshop.

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

tablet_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_tab-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78623” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

mobile_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_mob-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78158” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

The post Using a Flat Picture Style for Better Finished Images by Rick Berk appeared first on Digital Photography School.

You must be logged in to post a comment.