The post Getting Landscapes Sharp: Hyperfocal Distances and Aperture Selection appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Elliot Hook.

Want to know how to master depth of field and hyperfocal distance – so you can capture consistently sharp landscape photos?

You’ve come to the right place.

Because in this article, I’m going to tell you everything you need to know about hyperfocal distance.

And by the time you’ve finished, you’ll be able to confidently use it in your own landscape photography.

Let’s get started.

Keeping your landscape photos sharp: depth of field

Great landscape photos generally have all of their key elements sharp.

This includes foreground objects that are just meters from your camera, as well as background elements that are kilometers away.

So how do you achieve such perfect front-to-back sharpness?

By ensuring that your depth of field is large enough to render everything of interest suitably sharp.

Let me explain:

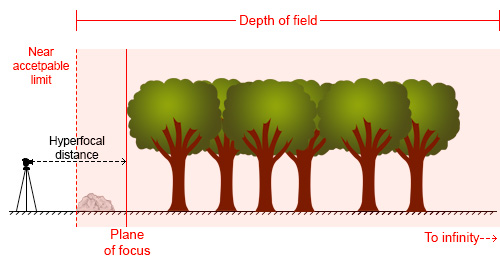

When you focus on an individual point within your landscape, you are creating a plane of focus that lies parallel to the sensor.

Everything in front of and behind that plane is technically not in focus. But there is a region within which objects will appear acceptably sharp – even though they’re not in focus!

That region is the depth of field.

Put another way, the depth of field is the range of acceptable sharpness within a scene, moving outward from the point of focus.

For instance, in the graphic below, the camera is focused on a rock:

So the plane of focus sits parallel to the sensor at that rock, and the limits of acceptable sharpness that form the edges of the depth of field lie in front of and behind that plane.

If you were to fire the shutter button on that camera, you’d get a photo with a sharp rock. The front of the first tree would be sharp, and the rest of the trees would fade into softness.

Make sense?

Factors affecting depth of field

Thus far, I’ve talked about depth of field as if it were a fixed property.

But it’s not. Your depth of field can change depending on three key factors:

- Focal length

- Aperture

- The distance between the camera and the point of focus.

Let’s take a closer look at how each of these elements affects depth of field, starting with:

Focal Length

A short focal length (e.g., 20mm) will give you a greater depth of field than a long focal length (e.g., 400mm).

So while it’s easy to keep an entire scene in focus with a wide-angle lens, you’ll struggle to do the same with a long telephoto.

Of course, changing your focal length will alter your field of view and therefore your composition, so you should rarely adjust your focal length to change the depth of field. Instead, select your focal length, frame your composition, and then use the next factor on this list to achieve the perfect depth of field:

Aperture

A narrower aperture, such as f/16, will produce a deep depth of field. A wider aperture, such as f/2.8, will give you a shallow depth of field.

So if you’re after an ultra-sharp, deep-depth-of-field shot, you’ll want to use a narrow aperture.

But be careful; extremely narrow apertures are subject to an optical effect called diffraction, which will degrade image sharpness. So while you should absolutely use aperture to adjust the depth of field, be on the lookout for blur.

Distance to the point of focus

If your focal point is close to the camera, then you’ll get a shallower depth of field. If your focal point is far from the camera, you’ll get a deeper depth of field. So if you shoot a distant subject, it’ll be much easier to get the entire scene sharp!

In other words:

To increase the depth of field, you can either choose a more distant subject…

…or you can back up to frame a wider shot.

Note that these three factors work together to determine the depth of field.

No one factor is important than any of the others; instead, they’re three variables in the depth of field equation.

So if you want a deep depth of field, you could use a narrow aperture or move farther away from your subject or use a wide-angle lens.

(You could also do all three of these things for an ultra-deep depth of field.)

And if you want a shallow depth of field, you could use a wide aperture or move closer to your subject or use a telephoto lens.

Keeping the entire scene sharp with hyperfocal distance

If you’re dead-set on capturing a scene with front-to-back sharpness, then you’ll need to understand another key concept:

Hyperfocal distance.

Hyperfocal distance is the point of focus that maximizes your depth of field.

In fact, by focusing at the hyperfocal distance, you can often ensure that the entire scene is sharp, from your nearest foreground subject to the most distant background element.

Look at the graphic below:

Do you see how the area from the point (or plane) of focus onward is sharp?

That’s what the hyperfocal distance will do for you.

And it’s the reason landscape photographers love using the hyperfocal distance.

Because by selecting a narrow aperture, and by moving the point of focus to the hyperfocal distance, you can render the entire scene in focus – for a stunning result!

(By the way, when focusing at the hyperfocal distance, the near acceptable sharpness limit is half of the hyperfocal distance.)

Now, you’re probably wondering:

How do you determine the hyperfocal distance when out shooting?

Technically, you can do a mental calculation, but this can get pretty complex. So I’d recommend you use a hyperfocal distance chart or calculator (there are plenty of apps for this, such as PhotoPills).

Eventually, you’ll be able to intuitively identify hyperfocal distances for common apertures and focal lengths – so you won’t even need to use an app!

Aperture selection and the dangers of diffraction

As you should now be aware, a narrow aperture deepens the depth of field.

So if you want your entire scene sharp, you generally need a narrow aperture.

Unfortunately, choosing your aperture isn’t as simple as dialing in f/22. Thanks to diffraction, if you set such a narrow aperture, you may get the entire scene in focus – but still end up with a blurry image.

For example, the image below shows a comparison of the same scene, shot at f/8 (left) and f/16 (right):

The frosty fern leaf is an important part of the foreground interest here. And though both images look perfectly sharp when resized and compressed for browser viewing, the 100% crop for each image below shows a significant difference in detail:

Do you see how the image on the right (taken at f/16) is blurrier than the image on the left (taken at f/8)?

That’s diffraction at work.

And note that, for the scene in question, both apertures resulted in a depth of field that extends from before the fern leaf to infinity.

(In other words: The blurriness has nothing to do with depth of field.)

Diffraction becomes an issue in all lenses as the aperture gets smaller, though it is more pronounced on inexpensive lenses. Typically, the sweet spot, in terms of lens performance, is somewhere between f/8 and f/11.

So when selecting your aperture, you’ll want to keep your lens as close to the sweet spot as possible, while also ensuring sufficient depth of field.

Getting landscapes sharp: conclusion

Now that you’ve finished this article, you can hopefully see that it’s worth understanding hyperfocal distance, aperture selection, and how they affect each other.

So make sure you find a nice hyperfocal distance app.

And remember to avoid tiny apertures (because they cause diffraction).

That way, you can get consistently sharp landscape shots!

Now over to you:

Do you struggle to keep your landscape photos looking sharp? Do you think an insufficient depth of field is the culprit? Or is it diffraction? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

The post Getting Landscapes Sharp: Hyperfocal Distances and Aperture Selection appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Elliot Hook.

You must be logged in to post a comment.