|

| Mount Rainier, captured from the trail up Mount Teneriffe, near North Bend in Washington State. ~200mm (equivalent), ISO 800. Still another 2 miles to go until lunch, and another 400mm to go before the RX10 III’s maximum telephoto setting. |

Sony’s new Cyber-shot RX10 III might look a lot like the older RX10 II, but its lens is really something else. With an effective focal range of 24-600mm, the RX10 III is one of the most versatile cameras we’ve ever used. But focal range is only part of the story – it’s optical quality that impresses us most. And boy, are we impressed.

See our updated Sony RX10 III real-world sample gallery

Hiking with the Sony Cyber-shot RX10 III

A very short shooting experience by Barnaby Britton

Caveat: This is not a review, nor is it sponsored content. This is a shooting experience based largely on a single day of picture-taking, during a hike. Four miles up a mountain in the sunshine, four miles down in the dark. One memory card half-filled, one battery half-emptied. All shots were processed ‘to taste’ from Raw and all are un-cropped. Your mileage (both literal and figurative) may vary.

I’ve been searching for the ideal hiking camera for years. Since I moved to the Pacific Northwest I’ve tried and rejected DSLRs, fixed-lens primes, travel zooms, super-zooms and several iPhones. Recently, I’ve been packing my Ricoh GR II for its small size and sharp lens, but the lack of a viewfinder really limits its usefulness in some conditions.

The last time I brought a DSLR on a mountain hike I almost left it tucked under a rock on the trail, rather than drag it all the way up (that was the old, famously brutal Mailbox Peak trail, for any PNW natives reading this…).

|

| Pretty good flare performance, considering the complex lens. This shot was slightly adjusted in ACR to bring out a little detail in the shadows. 24mm equivalent, ISO 100. |

It’s been a few years since I experimented with a superzoom compact camera, after a couple of bad experiences with sub-par lens performance. I’ve always liked the idea of them, but all too often I’ve been disappointed by the results in practice. These days, though, as my colleague Jeff likes to remind me, the good ones are actually pretty good.

OK, sure, but ‘pretty good’ for a super zoom is only ‘OK, ish’ by the standards of a shorter-lens compact or interchangeable lens camera, right? Well, that’s what I thought, too. Until…

We knew the sensor is good from our experience of using the RX100 IV, but the Sony Cyber-shot RX10 III’s major selling point is its lens. And the lens in the RX10 III is, as far as I can tell, made of magic. I genuinely have no idea how Sony’s engineers packed a 24-600mm equivalent lens of such high quality into a camera this small. It defies all reason. From wide-angle all the way to extreme telephoto, the RX10 III’s lens delivers impressive results. Weirdly impressive.

|

| As well as distant details, the RX10 III is capable of capturing sharp images of tiny things, very close to the camera. Like these wildflowers. 24mm equivalent, ISO 100. |

Now, obviously I could take technically better shots with a DSLR and a fast zoom, or for that matter a prime lens compact like the GR II. Portraits with shallower depth of field, landscapes with critically better edge-to-edge sharpness and all the rest. But this past weekend a DSLR was out of the question. If I’m hiking up a mountain in 80+ degree weather, I’m traveling as light as possible. Most of the weight on my back this weekend was drinking water, and although it’s a fairly chunky camera, the RX10 III was light enough to clip onto the shoulder strap of my backpack with one of these.

|

| Mount Teneriffe on a hot day is a pretty demanding hike, but the view from the top makes it worthwhile. 40mm equivalent, at ISO 100. |

The Ricoh GR II is lovely, but I knew that from Mount Teneriffe I’d be looking at three peaks – Mount Rainier, Mount Baker, and Glacier Peak, as well as Mount Si and Mailbox, a little closer at hand. So 28mm just wasn’t going to do the job. We timed our hike so that the sun would be go down shortly after we summited, and I knew that I wanted a nice, closeup (ish) shot of Mount Rainier’s famous purple glow (see the picture at the top of this page).

|

Exposed for the highlights, it was easy to brighten shadow areas in this shot using Adobe Camera Raw. 24mm, ISO 100.

You can’t really see here, but just where the blade of grass meets the horizon to the right of my subject, is Seattle’s distinctive skyline. See below for a shot taken from the same vantage point at 600mm.

|

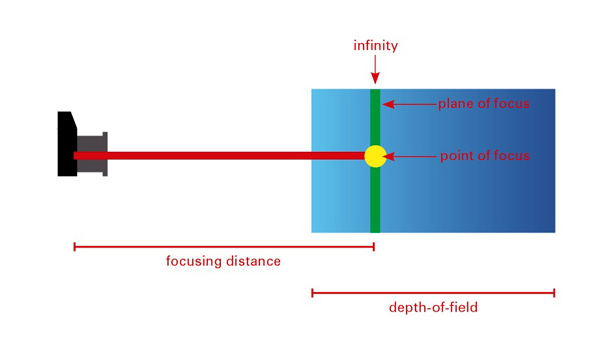

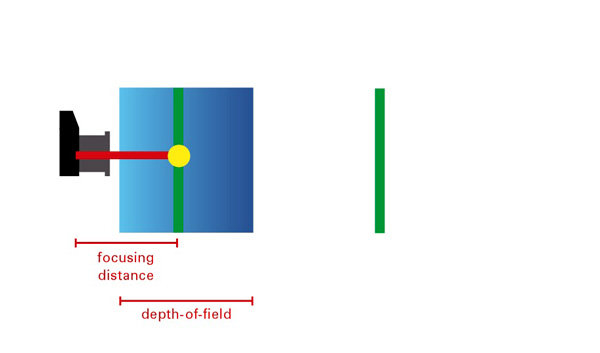

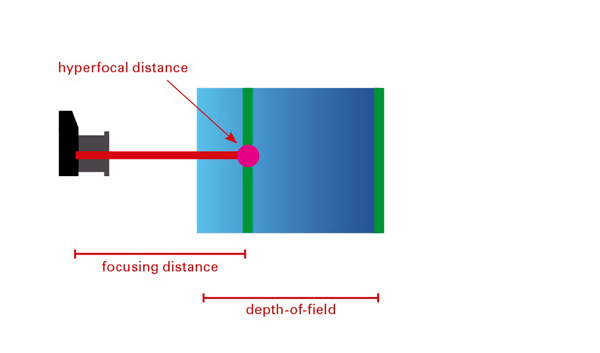

A lot of the prejudice about long zoom compact cameras comes from a misunderstanding of how to interpret their lens performance, especially at the long end. Atmospheric distortion and haze from moisture, pollen and pollutants will reduce the sharpness of any telephoto lens, especially on warm days.

So if your telephoto shots look like they were taken through a frosted bathroom window, the lens might not be the culprit. On the other hand, if everything in your pictures looks like someone went over the edges with a magenta highlighter pen – well, that’s the lens.

|

| Seattle at sunset, from almost 40 miles away. 600mm equivalent, at ISO 100. Moderate ‘dehaze’ applied in Adobe Camera Raw. |

I had no such issues with the RX10 III (which was reassuring, since it costs $ 1500) but as always, I was shooting Raw, so what little fringing I did see in my images was easy to correct. Likewise, Photoshop’s ‘dehaze’ control in Camera Raw came in very useful to bring back some clarity to images taken at the telephoto end of the RX10 III’s lens.

|

| Mount Baker, seen through more than 90 miles of pollen-laden air, just before sunset. This shot didn’t require quite so much dehazing as the last one. 600mm equivalent, ISO 250. |

During a day’s shooting during which my hiking partner and I walked a roundtrip of about 13 miles up and down a 4500ft peak, the RX10 III nailed virtually every shot. And that’s everything from a knee-level picture of some tiny wildflowers a few centimeters away from the lens, to a 600mm capture of Mount Baker, 90 miles away from my vantage point and half lost in haze (above).

|

We hiked about half of the trail back to the car in the dark. For the last half mile we were accompanied by an owl. This grab shot was taken at ISO 12,800, by the light of our headlamps. At 95mm equivalent, there’s no motion blur at 1/15sec. |

From these sunset landscapes to ISO 12,800 snapshots of an owl that followed us back to our car at the trailhead, every time I looked at something and went ‘oooh’ and tried to take a picture of it, the RX10 III – and its insanely wide-ranging lens – got me the shot that I wanted.

|

| Hiking through the forest just before sunset. 50mm equivalent at ISO 6400. |

We’re working on a more scientific assessment of the RX10 III’s lens right now, but in the meantime, I hope you enjoy our updated samples gallery (now with Raw files!).

I’ve only been using the RX10 III for a few days, and there are plenty of things I don’t like about it (confusing menus, clunky ergonomics, no touchscreen, laggy GUI, the aluminum lens and focus rings scratch the minute you look at them) but somehow, despite all that, I’m already planning next week’s hike.

$ (document).ready(function() { SampleGalleryV2({“containerId”:”embeddedSampleGallery_0737303360″,”galleryId”:”0737303360″,”isEmbeddedWidget”:true,”standalone”:false,”selectedImageIndex”:0,”startInCommentsView”:false,”isMobile”:false}) });

Articles: Digital Photography Review (dpreview.com)

My ebooks Understanding Lenses Part I and Understanding Lenses Part II will help Canon EOS owners decide what lenses to buy for their cameras. They are both filled with lots of tips to getting the most out of your Canon lenses. Click the links to learn more.

My ebooks Understanding Lenses Part I and Understanding Lenses Part II will help Canon EOS owners decide what lenses to buy for their cameras. They are both filled with lots of tips to getting the most out of your Canon lenses. Click the links to learn more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.