The drama of ‘39

|

| ‘The Open Door’ William Henry Fox Talbot. About 1843. Print from paper negative. |

On January 6, 1839, François Arago, Secretary of the French Academy of Sciences, announced Daguerre’s invention and spoke of his accomplishment publicly, although he said nothing of the specific methods involved.

By the middle of January, news of Daguerre’s invention had spread everywhere. Today, when imaging is so common and taken for granted, it’s hard to imagine how amazing the idea of taking a picture was in 1839. It created immediate headlines around the world.

|

| Francois Arago painted by Charles Steuben, 1832. |

The actual techniques used remained secret, however, since the French government had not yet officially bought the invention from Daguerre. The secrecy led to some suspicion that this was a trick or fake, and just like today, a few people ‘proved’ it was impossible. Most believed, though. This was an era when revolutionary new technology became available almost every year.

Who is this Arago of whom you speak?

For we photography types, Dominique François Jean Arago is just the guy who announced Daguerre’s invention, but in fact he was way more than that. He was born in a tiny village, graduated from a small college in 30 months, passed the examinations to enter the Ecole Polytechnique, got bored there, and went to work at the Paris Observatory. In 1806 he led an expedition to measure the Paris Meridian (which was used both to measure the size of the earth and to determine the length of a meter), became a prisoner of war, and on his release became the youngest member of the French Academy of Sciences at age 23.

Despite having left the Ecole Polytechnique as a student, he returned as the Chair of Analytic Geometry at age 27. He did work in magnetism and optics, confirming Fresnel’s wave theory of light and making important discoveries in the polarization and emission of light.

This is part of the reason he was so taken with Daguerre’s discovery; to Arago, photography was ‘the freezing or capture of light waves’. He may have gotten a bit too excited, though, as he really didn’t have the authority to make the purchase he promised Daguerre.

The chaos begins in England

The announcement of Daguerre’s achievement wasn’t published in England until January 19th – the telegraph wasn’t in use yet so dispatches went by rail and boat.

Let’s do an Aside!

Speaking of telegraphs, Samuel Morse, generally considered the inventor of the ‘modern’ telegraph, was in France trying to sell his telegraph system in 1838 and was introduced to Daguerre. Daguerre showed Morse his cameras, Morse demonstrated his telegraph to Daguerre, and they had an inventor-bromance-at-first-sight. Daguerre gave Morse a copy of his photographic instructions in the summer of 1839 before Morse returned to America.

Morse hadn’t sold his telegraph yet, so he supported himself by opening the first photography studio in the United States and teaching others photography*. Most of the early American photographers including Samuel Broadbent, Albert Southworth, Matthew Brady, Albert Sands, and Jerimiah Gurney were taught by Morse.

|

Samuel Morse, taken about 1840. The Morse family claimed the image was taken by Daguerre but this is unlikely, since the image is not a Daguerreotype. |

But wait! There’s more! Why was Morse in France? Because the Germans, who were his original sales target, already had a crude telegraph in place, invented by their own Carl Steinheil. In 1840, Steinheil became the first German to use Daguerre’s methods and made some clear improvements to them; making negatives and then printing positives from them. He became more interested in photography than the telegraph, and eventually founded the Steinheil optical company which made cameras, lenses, and telescopes until the 1970s.

So, the two great advances of the 1840s, photography and the telegraph, are quite intertwined.

Back to England

William Henry Fox Talbot, he of too many names and too many interests (he had set aside his development of photography to work on an archeology book), heard of Daguerre’s invention as soon as it hit the English papers. His reaction was immediate, arrogant, and overblown — which would characterize most of his reactions for the rest of his life. After reading of Daguerre’s camera, he wrote (in typical Talbot dramatic fashion) that he was “placed in an unusual dilemma, scarcely to be paralleled in the Annals of Science”.

Talbot wanted both public credit and financial gain for his work on photography. Having no idea if Daguerre’s methods differed from his own, he immediately tried to establish precedence as the first inventor, filing patents for ‘making permanent images using a camera obscura’ (the only thing he knew Daguerre used). He rushed samples of his ‘photogenic drawings’ to the Royal Institute in London where they were exhibited on January 25th, only weeks after Daguerre’s announcement. He provided documentation that they had been taken as early as 1835, hoping that would make his images the earliest. (They weren’t).

Then he wrote letters to Arago and other academic societies stating that he would file disputes regarding the priority of Daguerre and presented a paper with the catchy title of “Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, or, the Process by which Natural Objects May Be Made to Delineate Themselves without the Aid of the Artist’s Pencil”. Once he learned that Daguerre made positive images on silver plates, Talbot filed more patents: for images made on paper, for making negative images, and for printing positive images from negative images.

Talbot Wasn’t All Bad

You may have gotten the impression I don’t much like Fox Talbot, probably because I don’t like Fox Talbot much. I will actually taunt him a second time later in this article. But he was an intelligent man, a polymath and linguist who did work in mathematics, chemistry, botany, Egyptology, and art history. He published 6 books and almost 60 scholarly articles and was one of the premier translators of Assyrian cuneiform. He discovered Talbot’s Law, which determines the frequency at which interrupted images appear continuous, something Edison used when developing cinematography. And, of course, the calotype and photogravure are Talbot’s inventions. So, I give the man his due; he did good science. He was just an insufferable jerk about it.

Hershel does science for the win…

Sir John Hershel, an acquaintance of Talbot’s and one of the premier scientists of the day, read of Daguerre’s achievements and then of Fox Talbot’s exhibition at the royal society in late January of 1839. With basically no other knowledge than ‘photographs had been’ made he wrote in his journal:

Since hearing of Daguerre’s secret and that Fox Talbot has something of the same kind, obviously, there are three requisites:

- Very susceptible paper

- Very perfect camera obscura

- Better means of arresting the further actions of light.

Within a few days he had sensitized paper with silver salts and made images — in fact he was exhibiting his own photographs within weeks. He was aware that both Daguerre and Talbot could not permanently fix their images, which slowly deteriorated over time. He knew that hyposulphite of soda (sodium thiosulfate) dissolved silver salts, so he used this to fix his images permanently. Rather than take out patents, he notified Daguerre and Talbot of this, and they both adapted “hypo” (as it has since been known to photographers) as their fixative. It remained in use for over a century.

|

| Sir John Herschel looking quite back-to-the-futureish, etching from portrait by Evert Duyckinick, 1873. |

Hershel also found Talbot’s terms ‘photogenic drawing’, ‘reversed copy’ and ‘re-reversed copy’ rather cumbersome and coined the terms ‘photography’, ‘negative’, and ‘positive’. Hershel also experimented with non-silver chemicals in an attempt to make the photographic process less expensive. He found he could create a similar light sensitive process using iron citrate and potassium ferricyanide which resulted in bright blue images: the Cyanotype. The low cost of this process (and the fact that Hershel didn’t patent) made it popular for photography for a while, especially for scientific images, like those botanist Anna Atkins made. Cyanotypes later became the engineering printer of the times; the blueprint.

…and pours some gasoline on the fire

Trying to calm the furor over in England, Arago invited Hershel, Talbot, and other English scientists to come to Paris to view Daguerre’s work. Talbot was too busy filing patents and refining his technique, but Hershel went. Much to Talbot’s dismay, Hershel wrote publicly:

. . . compared to these masterpieces of Daguerre, Monsieur Talbot produces nothing but vague, foggy things. There is as much difference between these two products as there is between the moon and the sun.

Probably not realizing that Talbot was taking all this very personally, rather than scientifically, Hershel wrote directly to Talbot in a letter:

It is hardly too much to call them miraculous. . . every gradation of light and shade is given with a softness and fidelity which sets all painting at an immeasurable distance. His [exposure] times are also very short. In a bright day three minutes suffice.

There is no question Hershel’s description was accurate. The difference between a Daguerrotype (below) and Talbot’s images of the time (the image at the top of this article) is dramatic.

|

| Daguerrotype of the Clark Sisters, circa mid 1840s. Photographer unknown. Image in public domain via Library of Congress. |

Talbot, who initially required 30 minutes, at least, to expose an image, must have tossed his breakfast after reading Hershel’s letter. But Talbot was a stubborn man and just continued to insist his way was the right way. It was the right way, of course, but it would be a few years before that became apparent. Largely because of Talbot.

Daguerre’s triumph

At this point, May of 1839, Daguerre was still waiting for the French Government to actually pay for his invention. Arago wanted to make it “a gift to the world” but Daguerre wasn’t that altruistic. He didn’t wait idly, however. He’d taken a rather broad interpretation of Argo’s definition of the world and decided that meant France. Plus he was aware of Tablot’s actions so he quietly had an agent take out patents on his invention in England.

Daguerre also arranged for his brother-in-law, Alphonse Giroux, to produce a wooden camera with lens supplied by Chevalier and a complete set of chemicals for his process. Each bore on its side a metal label “No apparatus is guaranteed unless it bears the signature of M. Daguerre and the seal of M. Giroux”. Giroux and Daguerre already were mass-producing these before the official announcement of his process and were selling them minutes after the announcement was made.

|

The most recent auction sale of an original Giroux camera, image from Westlicht Photographia Auction, 2010. If you find one at a garage sale, grab it. They sell for about $ 1 million in reasonable condition. |

On July 19th, the French Government finally passed a bill giving Daguerre a lifetime pension in return for his process (and a smaller pension for Isidore Niepce). On August 19th the details of the process were made public at a joint meeting of the French Academies of Science and Fine Arts. The event generated more excitement than a Talking Heads reunion tour: people arrived three hours early to find the hall already full and crowds lining the street. Within days every optician and chemist in Paris (and elsewhere for that matter) had sold out of lenses, silver nitrate, silver plates, and everything else needed to create photographs.

The effects of the release were huge. Photographers were soon swarming over every bit of photogenic real estate in Paris, making image after image (real estate because the early Daguerrotypes required exposure times too long for portraits). Many were making artistic images, but just like today, others quickly became more enamored with their equipment’s resolution. A lament written at the time (which may be apocryphal) would be perfectly at home on a DPR forum today.

Our young men should spend more time considering the composition and merit of their images, and less time with magnifying glasses counting how many bricks and shingles they can resolve.

Daguerre retired almost immediately to Bryn-Sur-Marne where he wrote a 79-page book on his process that was immediately translated into a dozen languages. He continued quiet experimentation in photography until his death in 1851.

The exposure times shortened quickly as chemical processes were refined. Within a year Daguerrists, as they were called, had set up portrait studios in every major city of the world. Even smaller cities were visited by traveling Daguerrists. For the first time an image of a family member could be made easily and then kept forever.

Hippolyte and Hercules

If you remember from the last article, two members of the “greatest names in photography” team, Antoine Hercules Florence and Hippolyte Bayard had also developed photographic techniques at this time. Hercules, a Frenchman living in Brazil, had only delayed and incomplete knowledge of the events in Paris. When he did become aware, though, he was the perfect gentleman stating only that his techniques were not nearly as advanced as those of Daguerre and making no claims for himself.

Hippolyte Bayard had approached Arago in 1839, presenting his own techniques which created positive images, like Daguerrotypes, but used less expensive paper, like Talbot’s process. Arago feared Bayard’s claims would interfere with his plan to release the Daguerrotype process “as a gift to the world”, asked Bayard to remain quiet, and inferred that he, too, would get some form of government pension. This didn’t happen and Bayard ended up demonstrating his technique to the French Institute in exchange for enough money to buy some chemicals.

|

| Portrait of a Drowned Man. Hippolyte Bayard, 1840. |

Bayard, who loved him some drama, used his technique to create the first staged photograph: “Self Portrait As a Drowned Man” which he exhibited at the French Institute with the following caption:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life…!

Hippolyte got his stuff together after a bit, though, and went on to have a most successful photographic career. Shooting Daguerreotypes.

Talbot snatches defeat from victory

Back in England Talbot continued to work on his process, making a huge discovery: the principle of developing a latent image. He found that if he bathed his silver iodide papers in a solution of gallic acid and silver nitrate after a brief exposure, the latent image (invisible at first) would “develop” and become visible. He then “fixed” his negatives in hypo and printed positives as he always had. This both shortened exposure times and improved image quality significantly.

It is this process, the Calotype, that became the forerunner of film photography. Calotype images were markedly improved over Talbot’s early work. They still didn’t provide the superb detail of a Daguerreotype, but they had one huge advantage: one could make multiple prints and create mass media.

Talbot patented his invention in England, but charged such high patent fees (up to £800) that almost no one in England used the process. A group of opticians, chemists, and photographers began a long series of legal battles attempting to overturn Talbot’s patents. But the more they tried, the more stubborn he became, and the patent wars raged on for nearly a decade.

However, Talbot, being quite the Anglophile, had patented his process in England and Wales, not bothering to patent it in Scotland and other countries. Daguerre, if you remember, had patented his invention in England, but not elsewhere.

|

| Papal Palace at Avignon. Charles Nègre. Print from a paper negative, 1852. |

Largely for this reason, England lagged behind the rest of the world in photography for quite a while, while Scotland and France became centers of photography. Scottish photographers, for example, could use either the Calotype or the Daguerrotype processes without paying any royalties; photographers in England had to pay royalties for either process.

A number of French photographers took advantage of the situation and began using Talbot’s process. It probably didn’t help Talbot’s mood much that Frenchmen made two dramatic improvements to his technique. The first, waxing the paper used in the process, increased the photographic detail significantly. Édouard Baldus, Gustave Le Gray, Henri Le Secq, and Charles Nègre were printing superb images using this process in the 1840s. In France. But no one did in England.

The second improvement, the albumen process, was developed by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, who published and made it freely available in 1847. This used albumen from egg whites to bind photographic chemicals to paper, creating a glossy surface and allowing thousands of positive prints to be made from a single negative. (Talbot’s technique allowed for, at most, a few hundred).

|

| The Hypaethral Temple, Philae. Albumen print by Francis Frith, 1857. |

With these advances, Calotypes became THE photographic method used by explorers, archeologists, and others publishing their photographs or documenting their travels in book form; they just didn’t print the books in England. As for Talbot himself, he made hundreds of Calotypes and published some of them in a series of booklets entitled “The Pencil of Nature”, which was the first published photography book. It came out as ‘fascicles’ of twenty-four plates each, but it was not a commercial success and was terminated after the first six fascicles were released.

The real father of photography?

While Talbot was vigorously defending his English patents, another Englishman, Frederick Scott Archer, developed a new technique in 1848. The collodion (or wet plate) process, used glass coated with a gelatin to hold the silver chemicals. Archer did not patent, publishing his technique so that others could use it freely. The collodion (or wet plate) technique was relatively inexpensive, exposed quickly, and the glass plate negative was easier to print from.

Talbot, being Talbot, sued wet-plate photographers on the grounds that this technique was just like his own. British photographers rallied to the case and brought reams of evidence that Talbot was not the true inventor (much of the evidence was later found to be false and fabricated). The jury found that Talbot’s patents were valid, but only for his exact process. Anyone who varied from his published methods even slightly was not guilty of patent violation, and by that time all photography varied from Talbott’s original methods.

Talbot had finally lost the war, and England had finally joined the rest of the photography world. Archer’s wet plate technique itself advanced photography greatly, but the fact that it led to the breaking of Talbot’s patents particularly advanced the art in England.

Frederick Scott Archer, unfortunately, benefitted not at all and died penniless in 1857. After his death, Punch magazine asked for donations for the family:

The inventor of Collodion has died, leaving his invention, unpatented, to enrich thousands, and his family unapportioned to the battle of life. Now, one expects a photographer to be almost as sensitive as the Collodion to which Mr. Scott Archer helped him. . . you, photographers, set up Gratitude in your little glass temples of the sun, and sacrifice, according to your means, in memory of the benefactor . . . answers must not be Negatives.

About £767 were raised for Archer’s family; a fair amount of money at the time. About as much as Talbot charged for one license to use the Calotype process.

The collodion process wasn’t perfect. Collodion (nitrocellulose), which is made from gun cotton dissolved in ether and alcohol, has an annoying tendency to explode, for one thing. Preparation of the plates and photographic technique using them was difficult. But the images obtained were better than Calotypes and created negatives that could print thousands of copies, unlike Daguerrotypes.

Direct positive images would continue to be made, not only Daguerrotypes, but less expensive Tintypes and Other types. Because of their fine detail, positives were a favorite for portraits for quite a while. But the negative-image-to-positive print process would become the standard for most photographic work.

So, who was the real Father of Photography? It would make a good paternity suit. Niepce created the first permanent images using a camera. Daguerre perfected the technique that allowed it to become mainstream (and was the only one to benefit financially). Talbot’s different technique allowed multiple copies of images to be mass produced, and the negative-image to positive-print is the basis for all photography from the 1800s until digital.

But, I think no matter who you credit with fathering photography, Frederick Scott Archer, who freed photography so that anyone of reasonable means could afford to take photographs and whose discoveries led directly to the development of film, is the one who raised the child.

* Morse wasn’t the ONLY Daguerreotypist in America in 1839. Dauerre had contracted with Francois Gouraud to introduce and sell Giroux’s ‘official’ cameras in the U. S. and he arrived in the Fall of 1839. Another man, D. W. Seager took and exhibited a Daguerreotype in September of 1839, soon after he returned to New York from Europe.

Resources:

- Bankston, John: Louis Daguerre and the Daugerrotype. Mitchell Lane. Delaware.

- Daniel, Malcolm: The Daguerreian Age in France. Metropolitan Museum of Art, October, 2020.

- Daniel, Malcolm: William Henry Fox Talbot and the Invention of Photography. Metropolitan Museum of Art, October, 2020.

- Gustavson, Todd: A History of Photography from Daguerrotype to Digital. Sterling, 2009.

- Marien, Mary W: Photography. A Cultural History. 3rd ed. Prentice Hall. 2011

- Newhall, Beaumont: The History of Photography. Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2009

- Osterman, Mark and Romer, Grant: History of the Evolution of Photography. In: Peres, Michael (Ed.): The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography, 4th, ed. Elsevier, 2007.

Articles: Digital Photography Review (dpreview.com)

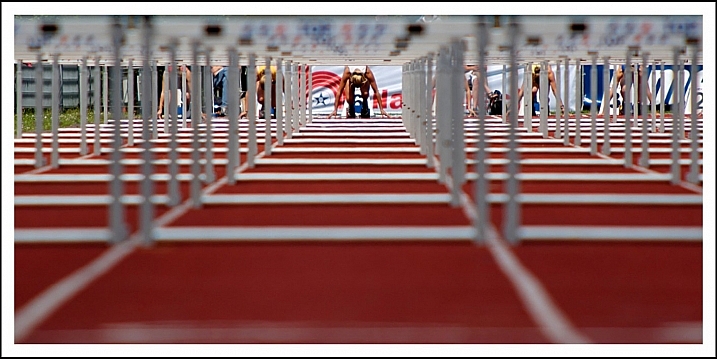

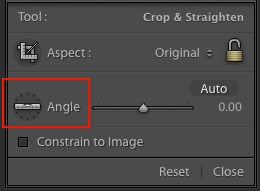

If you weren’t able to get a straight horizon in the field, there’s also a easy method to fix it in post-production.

If you weren’t able to get a straight horizon in the field, there’s also a easy method to fix it in post-production. While Automatic Mode may have its benefits for those who just bought their first camera, the sooner you stop using it the better. I always recommend mainly using Manual mode, even though both Shutter Priority and Aperture Priority are acceptable for beginners.

While Automatic Mode may have its benefits for those who just bought their first camera, the sooner you stop using it the better. I always recommend mainly using Manual mode, even though both Shutter Priority and Aperture Priority are acceptable for beginners.

You must be logged in to post a comment.