The post Photographing Artwork? These Tips Will Make the Process Much Easier! appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Glenn Harper.

Photographing artwork may seem like a simple task, but it’s often hard to do well. There are technical hurdles to overcome, like achieving an even exposure, avoiding reflections, focusing accurately, choosing the right aperture, and so on. In this article, I’ll give you some tips on photographing artwork that make the process much easier!

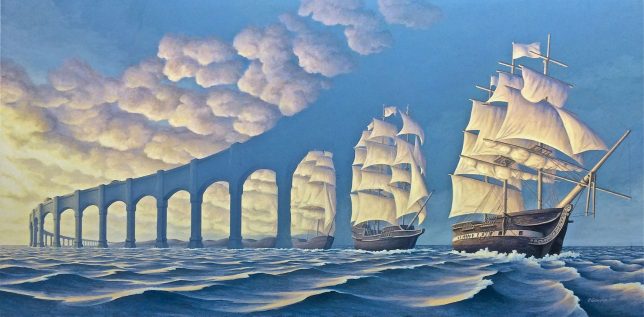

Detail from ‘The Ninth Wave’ (1850) by Ivan Aivazovsky. Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

Tips on photographing artwork

The tips I’m about to give mostly relate to 2D art, meaning paintings, drawings or prints in whatever form they come. I’ve photographed most of them, ranging from grand oil paintings in national museums to antique newspaper illustrations at home.

I will give a few tips on photographing sculpture, as well. Creating successful pictures of 3D art is not always straightforward.

White balance

When photographing artwork, white balance is not objective – there’s a creative decision to make. Do you want to preserve the color of the art as you see it or should you neutralize it and make the whites white? Will you be a historian or a restorer?

I could restore whiteness and original color in this Victorian newspaper with a single click, but using a gray card, I’ve reproduced its 125-year-old state. Lighting is overhead daylight.

Paper and paint tend to discolor with age, typically with yellowing. So, you have to decide if you want to copy what you see or turn back the clock. That’s assuming you’re correct in your assumptions about the original color.

To “correct” white balance, there are two main approaches:

- To make whites appear white: choose an area within the artwork that should be neutral in tone – preferably a mid-gray if one exists. By clicking on this area with a white balance tool, you’ll equalize the RGB values and, with any luck, correct color in the rest of the image. Problems arise when the artwork has aged more in some places than others, which tends to create ugly yellow blotches when you perform a WB adjustment.

- To preserve signs of aging: use a gray card to correct for the light illuminating the art, which keeps the existing color of the artwork including signs of aging. There will still be some slight shift in color since the appearance of all objects is affected by the light they fall under. But you’ll retain the overall appearance of age. You can always warm the photo up a bit if you want to emphasize the antique look.

A third option, if you have no neutral tones in the image nor any gray card, is to fiddle with color temp and tint sliders until you think the white balance is correct. Correcting color by eyesight is hit and miss, however, and never as accurate as using numbers.

One thing we know about snow is that it looks better white. Artificial lighting and/or aging make this painting come out yellow in a photo. A white-balance tool quickly restores it, though it’s hard to always know how a painting looked when fresh. Artist: Ferdinand Schmidt (c1900), La Piscine Museum, Roubaix.

The light source makes a huge difference to white balance. Avoid mixed lighting if you can. In museums, you won’t often find paintings under mixed light sources, but the same is not true of sculpture. A mixture of warm artificial light and window light causes strong orange or blue color casts in local areas of the picture. This can be hard to deal with in post-processing.

Art museums don’t tend to display paintings under mixed lighting, but you might find sculptures near a window. That will often result in blue highlights and orange shadows. Sculpture: Epicurus and Metrodorus, Louvre Museum.

Color correction, DNG profiles, light sources

We’ve talked about correcting white balance when photographing artwork, but you can take color correction further than that. You can also correct for the characteristics of the light source.

Fluorescent and LED light sources are more energy-efficient than old filament lights and don’t outwardly transmit heat. LED lighting is now very common in art museums. And yet its light is lower quality from a photographic viewpoint than that of halogen.

Modern light sources emit either a discontinuous or narrow-band spectrum, meaning they reproduce colors inconsistently and sometimes not at all across the visible spectrum.

Art museums and galleries use one light source to illuminate paintings. It might be overhead diffused light or spotlights on a track lighting system. Photo by Riccardo Bresciani from Pexels

To some degree, you can judge the quality of LED/fluorescent lights by their CRI rating. You need 90+ if you’re shopping for them, but a high rating does not make them equal to traditional light sources. The CRI test is a lenient, non-standardized test using a few color patches, so the difference between 95% and 100% is greater than the numbers suggest. Incandescent and halogen lamps score 100% by default.

One way you can improve color in your photos when shooting art under modern light sources is to create a DNG profile. For this, you use a product like the X-Rite Color Checker and either X-Rite or Adobe software. You then apply this profile at the raw-conversion stage if the software supports it.

This page from an antique WW1 history book is clearly being lit from the right. Note the X-Rite Color Checker includes neutral patches for correcting white balance as well as color patches for DNG profiles.

If you try to correct for LED or fluorescent lighting by eye, you are likely to need the “tint” slider in raw converters. These light sources vary greatly in their output along a green to magenta axis. Old filament lamps don’t behave the same way – their output always sits along the orange-blue Kelvin scale.

Window light – Pros and Cons

This old advertisement was on display outside. Though the color temperature of daylight varies, no other light source displays color so fully across the visible spectrum. KattenKabinet Museum, Amsterdam.

You’ll never beat daylight for its ability to display all colors of the visible spectrum with little bias. It’s an ideal light source for art. The only problem is you can’t control it very well. If you use window light to photograph a piece of art, the exposure will likely be uneven from side to side. There may be a stop or more difference. You can get this down to about half a stop or less if you use a reflector.

Of course, you can even up the exposure in post-processing. One thing you can do is photograph a blank card or piece of white paper under the same light, which makes uneven exposure obvious when you see it on the computer. Use what you see there to correct other photos in the shoot.

If you photograph a postcard by window light, flipping it over makes uneven exposure more obvious. The right of this photo is 25% brighter than the left.

Use adjustment brushes, layers, and layer masks or a graduated neutral density filter to correct uneven exposure across an image. On-image local adjustments like those found in DxO PhotoLab are good. A graduated filter is a smooth way of dealing with it, but you can just as easily use brushes with lots of feathering.

Perspective: positioning art for a photo

When photographing a 2D piece of art, position it flat against a wall or table and try to get the camera sensor perfectly aligned with it. Otherwise, you’ll see the same “keystoning” effect you get with architecture, where vertical lines diverge. The subject of the art will be slightly distorted if you take it at an angle, though not always to a degree anyone will notice.

One way you can align a camera with art is to use a spirit level on both. Test the surface that the art lies against to see if it is even, making adjustments with props if necessary (much like you would with a table leg on an uneven floor). Do the same thing with the camera, using a spirit level on the hotshoe or resting on a flat part of the camera in a tripod. It needn’t look professional if it does the job.

Ideally, you want the camera to be level with the center of the picture when photographing art. I haven’t done badly with this handheld shot, though it’s slightly wonky to the right (wall-mounted paintings might tilt slightly at the top). The correction will be moderate. Artist: Lucien Jonas (1880-1947), La Piscine Museum, Roubaix.

Spirit levels vary in their accuracy, but you’ll soon see if your method works or not with rectangular artwork. If it does, the horizontal and vertical edges will align with the 90-degree angles of your photo. If you’re off-kilter, you’ll see the slight keystoning effect.

Does this matter? You can correct perspective in editing software, but only with a loss in edge-to-edge sharpness.

The less you have to correct, the better.

Use spirit levels along with any perpendicular lines in the artwork to achieve the best possible perspective. Heavy corrections for keystoning after the fact have an adverse effect on image quality, which may or may not be noticeable depending upon intended use.

If all you’re doing is sharing a photo of a painting on Facebook, you don’t need to be fussy about aligning artwork and camera. Using sufficient depth of field will compensate for minor focusing errors and nobody’s going to pick you up on imperfect verticals! On the other hand, if you’re selling art online, you want to do the best job you can with the photos.

Lens choice and depth of field

A good choice of lens for photographing art is a 50mm or 100mm prime lens with decent close-focusing capability. Many people use macro lenses, not least because they create very little distortion at close range. A high-quality zoom will suffice at around portrait-length.

You needn’t choose a small aperture when photographing 2D art, since you don’t need much depth of field. Closing the lens down two or three stops to f/8 often produces optimum sharpness, whereas much more than that reduces sharpness by diffraction.

Focusing Accuracy & Live View

Without question, the most accurate way to focus on almost anything is to set your camera up on a tripod and use live-view mode with manual focusing. Needless to say, it doesn’t work so well for moving subjects, but it’s the perfect technique for artworks.

Using live view works well for 2D subjects but isn’t crucial unless you want perfect sharpness. You can focus adequately through an optical viewfinder and let depth of field take care of any minor errors.

For 3D subjects like statues, live view is invaluable. It overcomes problems like field curvature, inaccurate focusing screens or focusing points and misaligned mirrors & sensors.

I’m far from ready to take a picture here, but I’m lining up an antique postcard in live view mode on the tripod. One problem with flat artworks is keeping them flat for the picture. You can use pieces of high-quality masking tape and clone them out afterwards, but be very careful not to rip off the paper surface upon removal.

Technical issues often make it hard to achieve critical sharpness where you need it in statues – usually the face and eyes. You may not notice this unless you zoom into your photos 100%, but it’s easy for focusing to be slightly off, especially on large statues where you are shooting upwards.

You can’t rely on focusing points or focus/refocus techniques, as they don’t always work. Live view and manual focusing overcome that.

Avoiding reflections

When you’re taking a photo of 2D art behind glass, one of the biggest hurdles to overcome is reflections.

Sometimes it’s easier to move on to another subject, but there are ways of avoiding reflections in your artwork photos. Here are some of them:

- Do not use direct on-camera flash. It’ll create a hideous hotspot in the glass that is impossible to remove after the fact.

- Use directional light sources from the side – preferably two at equal distance (one at either side of the art). Non-directional light is softer but will create reflections from other items in the room.

- At a museum, wearing black clothes can help in photographing small art pieces as it shows up less in reflections and absorbs light from other light sources.

- Get friends or relatives in dark clothing to stand near the art and block reflections.

- Use a large black scrim/screen and push your lens through it to photograph the object – same reasons as black clothing but more effective.

- Use a polarizing filter to cut out much of the glare (increases exposure time or ISO, so not ideal for handheld shots in dim museums).

- Shoot at a slight angle to cut out reflections and adjust perspective in post-processing. Overdoing this will noticeably decrease edge-to-edge sharpness.

- Examine the artwork carefully for reflections that may not be immediately obvious – they have a habit of being more noticeable on a PC.

Capturing texture

If you want to capture texture in a piece of art (e.g. oil painting), the last thing you want is a diffuse light source like a fluorescent bulb. What you need is a directional light source from one side.

In oil paintings, revealing texture usually means some light will reflect into the lens, which can be distracting. It’s a question of controlling the effect so that spectral highlights don’t ruin the picture. A polarizing filter will help as long as it doesn’t make other shooting parameters unusable.

The reflections in this oil-painted portrait emphasize texture but they’re distracting. Like all spectral highlights, reflections in art need to be subtle and kept away from focal points.

Note that LED lighting is directional by nature. You can improvise at home by setting up LED narrow-beam G50 spotlights or similar. Otherwise, you can control diffuse artificial lighting or flash lighting with modifiers such as a snoot.

Few artists laid down paint more thickly or wildly than Vincent van Gogh. You can see light reflected in this detail from one of his paintings, but it’s subtle enough not to detract from the bigger picture. Photo from rawpixel.com / Yale University Art Gallery (Source)

Copy stands, light tables, and light tents

If you’re photographing fairly small artworks, you can be ultra-professional by using equipment meant for the job. Personally, I like to save money by using Heath Robinson methods, but not all the gear I’m going to mention is expensive. I might even talk myself into buying some of it…

Copy stands

Copy stands include a base, two lights, a column, and an arm to hold the camera. They’re ideal for photographing large volumes of flat art because they’re ready to go, whereas setting up a tripod, camera and lights takes time. Copy stands usually cost from around $ 200, but you can pick them up secondhand for less than half of that.

Light tables

Light tables are often used to create product photos with a clear, smooth white background. You could just as easily use one for small artworks and ornaments. A copy stand is a better bet if you want to record flat artworks without a background.

Light tent or cube

Light tents tend to be five-sided cubes held together by wire or plastic frames. The sides are made from a translucent material that allows diffused light through. Also supplied are various backgrounds. Some tents have an aperture in the top that lets you point the lens downwards. This is ideal for photographing small, flat artworks.

You need an even exposure for flat art, so lights of equal strength and distance either side of the tent are good. With sculpture, uneven lighting creates modeling and emphasizes form, so the set-up is different.

Light tents can easily be made at home by constructing a simple frame and covering it with translucent material. Photo: Alison Christine from North Yorkshire, UK [CC BY 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Light tents are often cheap to buy, unlike light tables and copy stands. They’re often flimsy, too, but they’re worth trying for a few bucks. No viewer is ever going to question technique or how much you spent on gear if the picture works.

Why photograph artwork instead of making it?

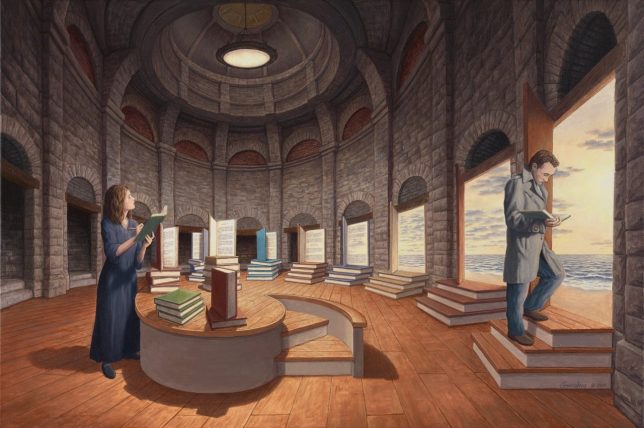

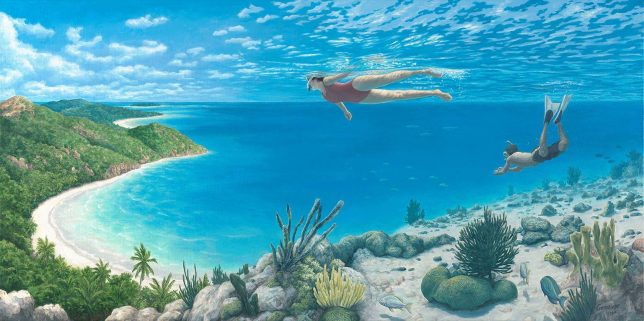

Photographing other people’s art may seem pointless, but it’s a useful exercise in developing your creative eye. That’s especially the case if you isolate areas of a painting or sculpture, which forces you to study art closely. There are often several pictures within a picture.

Within larger paintings, you’ll see delightful details. Here, a young girl distracts herself with flowers whilst possibly slightly bored at a wedding table. Artist: Albert Fourié (1854-1937), Musée des beaux-arts de Rouen.

The only activity I’d strongly advise against is making straight copies of work from living or recently-living artists (unless they are your client and they have commissioned you to do so) and trying to make money from them. Then, you’re on very thin moral and legal ice (in fact, you’ve fallen through it). Copyright durations vary from country to country.

Of course, you might be photographing your own art to share online or sell on eBay. There is no photographic motive purer than sharing. The desire to share is, after all, in the heart of most artists, no matter the size of the audience.

Do you have any other tips for photographing artwork that you would like to share? Please do so in the comments.

The post Photographing Artwork? These Tips Will Make the Process Much Easier! appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Glenn Harper.

Digital Photography School

.jpg?resize=1500%2C1001&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1001%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1001%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1001%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1001%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1001%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=844%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=717%2C403&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1500%2C1001&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1500%2C1001&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1500%2C1001&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1500%2C843&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1001%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1001%2C1500&ssl=1)

.jpg?resize=1500%2C844&ssl=1)

You must be logged in to post a comment.