There’s a scene in the original Jurassic Park movie, that almost perfectly describes one lesson I have learned when documenting the world around me with my camera. In this scene Dr. Ian Malcolm, a brilliant mathematician who is visiting the prehistoric park, expresses severe reservations about the idea of resurrecting long-extinct species during a conversation with John Hammond, the director of the park. Hammond is gleefully explaining the incredible genetic breakthroughs that his scientists have achieved. “Our scientists have done things which nobody’s ever done before.” Incredulous, Malcolm responds with equal fervor and says, “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” The same holds true for camera lenses. Just because you can shoot wide open at f/1.4 or f/1.8, doesn’t mean you should.

When I first got into serious photography work, I was amazed at the power and light-gathering ability of my 50mm f/1.8 lens. It opened up a whole new world of photographic possibilities, that I continue to explore today, and was capable of producing incredible images, even on my humble little Nikon D200. Unfortunately, like the scientists in Jurassic Park, I did not spend years in the trenches learning my trade and honing my skills in order to learn how to truly utilize the power of such wide apertures, and went through a phase where I shot everything wide open because of things like low light photos, depth of field, and of course bokeh. Always with the bokeh. Now it’s important to note that I don’t regret any of those early lessons but I do want to offer youa few simple things I’ve learned over the years, and a couple reasons why you might want to reign things in a bit and not shoot wide open with that fancy prime or ultrafast zoom lens just yet.

1. Depth of field can be way too shallow

I shoot most of my photos with three prime lenses: a 35mm f/1.8, a 50mm f/1.8, and my favorite, an 85mm f/1.8, that I call my supermodel lens. (Seriously, you could just about point that lens at a moldy old scarecrow, and get a portrait worthy of Vogue magazine.) Each of these lenses has its own set of unique advantages and limitations, but as you can probably already tell, the one thing they all have in common is a super wide maximum aperture. Certainly there are plenty of lenses available with even bigger apertures, like the Nikon 58mm f/1.4 or Canon 85mm f/1.2, but when push comes to shove an f/1.8, or even f/2.8 lens, is no slouch either. Wielding one of these ultra-wide beasts can be a bit like riding a tyrannosaurus rex, in that the sheer amount of power at your disposal is kind of insane. But, one advantage of fast primes like this, an ultra-shallow depth of field, can also be somewhat of a curse if not used properly.

I’m not going to lie, it’s a ton of fun to shoot things with your lens wide open but it took me a while to learn, that just like the scientists of Jurassic Park, maybe I should have held back a bit. This portrait of a college student is yet another time in which I had no good reason to shoot wide open, but did anyway, and the result was a photo that simply could not be used. Due to the wide f/1.8 aperture, and my proximity to the subject, it left me with a depth of field consisting of just a few centimeters. Her left eye (on the right side of the photo) is perfectly in focus while the other side of her face is blurry, and the result is a strange-looking picture that I had to discard. Thankfully, I quickly realized my mistake and got some other perfectly usable images by shooting at f/2.8 and f/4. But, this was one of those situations in which I thought it would be super cool to get the way awesome background blur of an f/1.8 aperture, but did not realize how I nearly destroyed the portrait in the process.

85mm, f/1.8, 1/750 second, ISO 400

Here’s another example from when I first got my 50mm lens, and thought it was so cool to go around shooting all my pictures at f/1.8 – because my warped sense of logic told me that no depth of field could ever be too thin. As a result this picture of some crocuses contains an ugly streak across the center where one flower and a lot of dead grass is in focus while the rest of the image is a blurry mess. Shooting at a smaller aperture would have given me a smooth transition between in-focus and out-of-focus areas and a much more pleasing image overall.

50mm, f/1.8, 1/500 second, ISO 400

2. Bokeh and background blur can get out of hand

This is a bit subjective, and open to interpretation on the part of both the photographer and the viewer, but over the years I have found that shooting at the widest possible aperture in order to get the most possible bokeh, or background blur, things can go from artistic and interesting, to messy and incomprehensible very quickly. Bokeh is nice and can certainly be used to add an artistic flair to an image, but when overused, it can overpower the subject and ruin the picture. The following photo of a purple flower sticking up from a bed of grass shows this phenomenon in action.

The flowers are so removed from the background it’s almost like they are hovering in midair, and the effect is somewhat disconcerting, and borders on upsetting. Blowing out the background so much has removed any sense of place and context for the subject, and what’s left is a green and purple mess, that is neither artistically interesting, nor aesthetically pleasing.

3. Vignetting, chromatic aberration, and other optical oddities

Before I say too much on this subject perhaps I need to add a bit of a preface. Less expensive lenses can behave strangely when you shoot with them wide open, but more expensive glass is usually much better at this sort of thing. With that disclaimer out of the way, it’s important to understand some of the optical abnormalities such as vignetting, chromatic aberration, and softness, that often show up when your lens is opened up as far as it will go.

Vignetting is when the edges of your image look a bit darker than the rest of the picture, due to how light is manipulated inside your lens before it hits the image sensor inside your camera. It’s not too big of a problem on cameras with smaller sensors like APS-C or micro four thirds models, but it is certainly there, and even more so on full frame cameras.

Vignetting can be a major issue when shooting wide open. Notice how the centers of both images are equally exposed but the corners are much darker at f/1.8.

If you shoot in RAW, you can use Lightroom, Photoshop, or other such applications to mitigate most of the effects of vignetting if you want. Of course another solution is to use a smaller aperture, which tends to eliminate most vignetting altogether. Vignetting is not always a dealbreaker, and many photographers, myself included, actually prefer the subtle effects of a well-used vignette. You may find that you fall into this camp, in which case go right ahead and shoot at f/1.8 or f/1.4 to your heart’s content.

The other optical abnormality that often rears its ugly head at wide apertures is chromatic aberration, which might be a much bigger problem if you are not ready for it. This usually manifests itself as purple or green outlines or fringes, around places in your pictures with harsh contrast between dark and light. For example the image below was shot at f/1.8, and upon first glance, looks perfectly usable.

50mm, f/1.8, 1/3000 second, ISO 100. It looks Okay on first inspection, but all is not well up close.

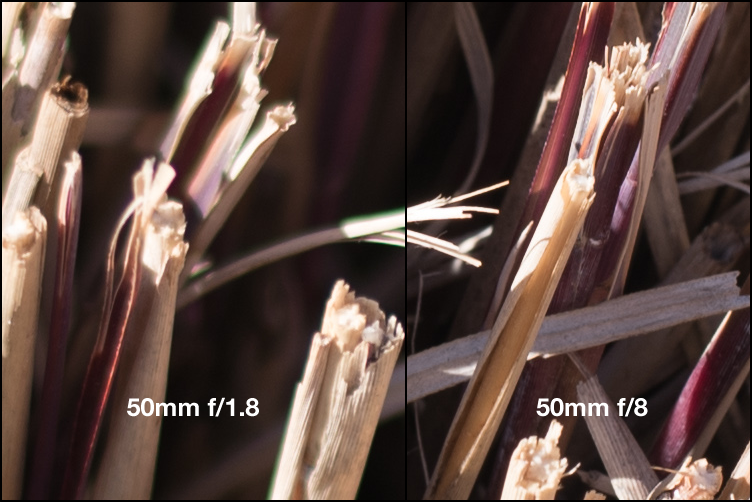

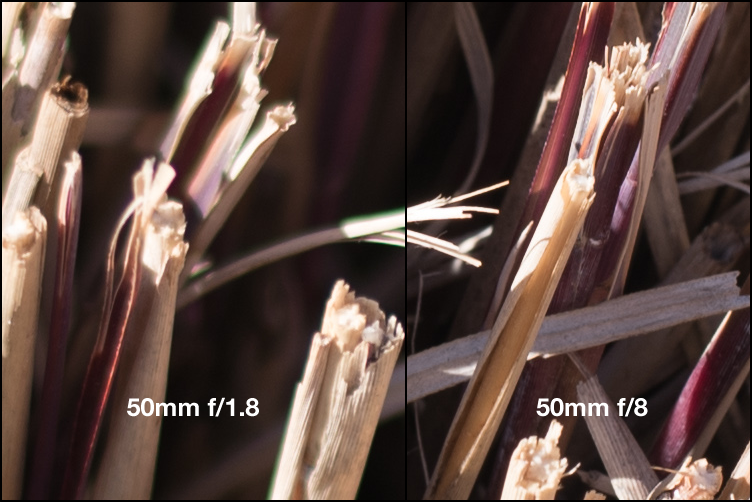

Take a closer look and you will notice a big problem around the edges of most of the dry stalks of grass. Ugly green halos show up all over the place, and this is a direct result of shooting wide open, due to how the incoming light is transformed by the lens on its way to the camera. Here’s a 100% crop of the image next to the exact same picture shot at f/8.

Green outlines abound on the left side while stopping down to f/8 eliminates them entirely.

This optical imperfection can often be mitigated somewhat in Lightroom, by using its: Remove Chromatic Aberration option in the Develop panel. But even then the results are not ideal, and you will often be left with images that still show some green or purple artifacts, or lose a bit of color from other parts of your picture. Rather than mess around with fixing these issues in post-production, I like to just avoid it from the start and shoot at a slightly smaller aperture. It usually fixes the problem, and still leaves me with the same overall composition I would have had with a wider aperture.

The last weird characteristic of most lenses at their widest apertures might not be that big of a problem unless you are painstaking examining your pictures on a per-pixel basis, but it’s something you should know about nonetheless. Almost all lenses are a bit softer when used at their widest apertures, which can result in pictures that are not quite what you want. The picture below was shot at f/1.8 and looks decent upon first glance, but a closer inspection reveals a very different story.

50mm, f/1.8, 1/125 second, ISO 100. Seems decent but once again a closer look reveals a much different story.

Zooming in on the exact center of the image, the point at which I locked focus, shows two very different pictures when this is put next to the very same picture shot at f/8.

Focus was locked precisely on the letter “K” and yet the image on the left, shot at the widest aperture on my lens, is much less sharp.

Once again this sharpness problem can be corrected to some degree in post-production, but my ideal solution is to avoid shooting at f/1.8 unless I specifically need the light-gathering ability, background blur, or other effects that such a wide aperture offers. Photography is all about tradeoffs, and while closing down the aperture on my lens resulted in a picture that was sharper, it also gave me an image that had much wider depth of field, which made the overall composition less pleasing.

4. Use wide apertures sparingly to maximize their impact

The Roman philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero once said, “Never go to excess, but let moderation be your guide.” This nugget of wisdom is applicable not only to life in general, but also speaks volumes about how to approach photography. I like to treat the widest aperture on my lenses like flooring the gas pedal on my car. It’s fun, but if I went around driving full speed everywhere I went, it would quickly lose its appeal. (Though in my 1998 Toyota sedan I would probably lose a race to a skateboarder, but you get the point.)

Your lenses have wide apertures for a reason and they are meant to be used to get good images, particularly if you are aware of some of the quirks and idiosyncrasies of using them like this. If you like shooting wide open, and don’t mind some of the potential tradeoffs like a bit of vignetting and chromatic aberration, then go for it! However, my own personal rule of thumb is to only use f/1.8 when I really need it, otherwise the creamy backgrounds and bokeh balls start to lose a bit of their luster. When I’m doing a portrait session I keep f/1.8 in my back pocket for when I really need it, otherwise I shoot most pics at f/2.8, f/4, or smaller.

I took most photos of this couple at smaller apertures, which made this one at f/1.8 stand out among the rest.

After hearing this list of reasons to hold back a bit when shooting wide open, I almost feel like I should write a similar article about the benefits of taking photos at the largest aperture possible. I don’t want to give the impression that you should never use your equipment to the fullest of its capabilities, just that there are a few things to know before you go around taking all your pictures at the widest possible aperture your lenses can use. You might end up with a few problems, just like the ill-fated scientists of Jurassic Park, but hopefully yours won’t be quite as lethal, and along the way you could very well manage to take some incredible photos too.

I’d like to know what your thoughts are on all of this, and if you have any favorite shots taken at not-quite-wide apertures, please post them in the comments below!

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

tablet_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_tab-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78623” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

mobile_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_mob-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78158” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

The post Are You Obsessed with Shooting Wide Apertures – Here’s Why You Might Want to Hold Back by Simon Ringsmuth appeared first on Digital Photography School.

Digital Photography School

You must be logged in to post a comment.