The post Aperture in Photography: A Beginner’s Guide (+ Examples) appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Darren Rowse.

What is aperture in photography? How does it work? And how can you use it to capture photos like the pros?

Aperture is an essential camera setting; in my opinion, it’s where the magic happens in photography. So in this article, I’m going to take you through all the ins and outs of aperture, including:

- What aperture actually is (in simple, easy-to-understand terms)

- How you can use aperture to capture artistic images

- How to choose the perfect aperture for landscape photography, portrait photography, and more

- Plenty of other tips and tricks!

If you can master aperture, then you’ll gain a huge amount of creative control over your photography.

Ready to take your photos to the next level?

Let’s dive right in, starting with the most important question of all:

What is aperture?

Aperture is the opening in the camera lens. A larger hole allows more light to hit the sensor, lightening your photos. A smaller hole allows less light to hit the sensor, darkening your photos.

And by adjusting the aperture setting on your camera, you can adjust the size of the aperture (and, in turn, affect a photo’s brightness).

Aperture and f-stops

Aperture is measured in terms of f-stops, also known as f-numbers. Like this: f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/22, etc.

As shown in the diagram below, the smaller the f-number, the larger the aperture hole:

Now, each full stop corresponds to a halving of aperture size. So when you go from f/2.8 to f/4, you cut the aperture in half. And when you go from f/4 to f/5.6, you cut the aperture in half again.

(Of course, to double the aperture size, you just go in the reverse direction: from f/5.6 to f/4, and from f/4 to f/2.8.)

So f/2.8 is a much larger aperture than f/22. And f/11 is a much smaller aperture than f/4.

Does that make sense? It can be confusing at first, especially because large aperture sizes correspond to smaller f-stop numbers and vice versa. But stick with it, and it’ll become second nature.

How does aperture affect your photos?

At this point in the article, you should know what aperture is: a hole in the lens that increases and decreases depending on your camera settings (i.e., your f-stop value).

But what does aperture actually do? How does it affect your photos?

In the next two sections, I’ll discuss the primary effects of aperture:

- Exposure

- Depth of field

Aperture and exposure

As you may already know, exposure refers to the brightness of a photo.

In general, the goal is to end up with a photo that’s not too dark and not too bright; instead, you want a shot that’s just right, one with lots of detail.

So where does aperture come into play?

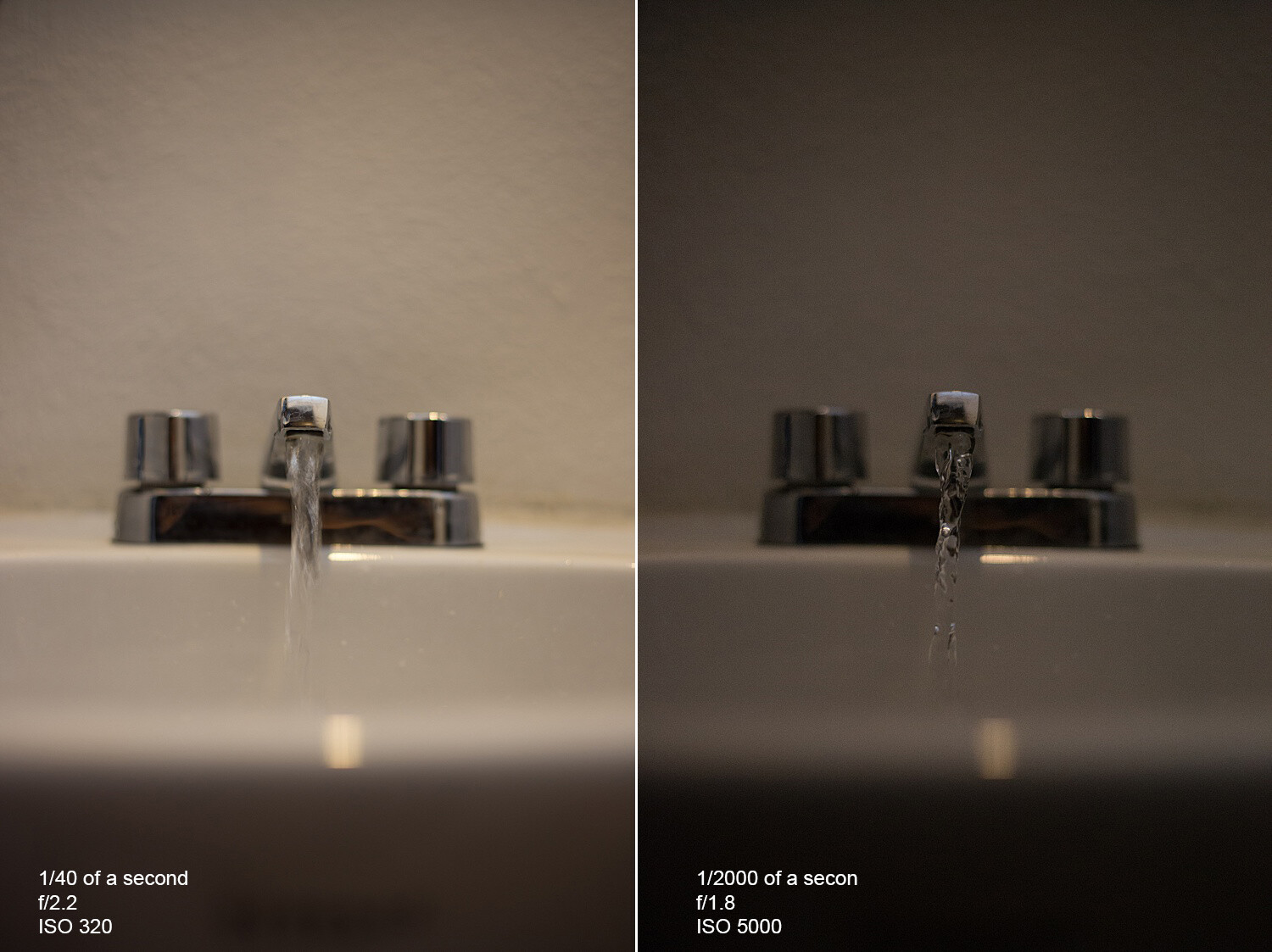

Aperture is one of the three key variables that affect your exposure. (The other two variables are shutter speed and ISO.)

Remember what I said above? By widening the aperture, you let in more light, which brightens your image. And by narrowing the aperture, you let in less light, which darkens your image.

So if you’re photographing a beautiful sunset and your photos keep turning out too bright, you can always narrow the aperture to darken down the image. (In fact, using a narrow aperture is often a good idea when shooting sunsets!)

And if you’re photographing a forest and your photos keep turning out dark and shadowy, you can always widen the aperture to brighten up the image. (As you might expect, this is a standard low-light photography practice.)

Of course, aperture isn’t the only variable that affects exposure. If you want to brighten a photo, you can also lower the shutter speed or boost the ISO. And if you want to darken a photo, you can raise the shutter speed or drop the ISO.

In terms of exposure, widening your aperture by a full stop has the exact same effect as lowering your shutter speed by a full stop or boosting your ISO by a full stop. A key consequence of this: different exposure variables can cancel each other out. Increase your ISO by a stop while decreasing your aperture by a stop, and you’ll end up with an identical exposure.

The point here is that, while aperture does determine exposure, you can’t think about it in isolation. Aperture, shutter speed, and ISO work together to give you a well-exposed (or poorly exposed) image.

Aperture and depth of field

Aperture also affects the depth of field in your photos.

What exactly does that mean? Well, depth of field (DOF) is the amount of your shot that is in focus. So a photo with a large depth of field will have most of the image in focus, like this:

Do you see how sharpness stretches from the foreground to the background? That’s thanks to the large depth of field.

A photo with a small depth of field, on the other hand, will have only a sliver in focus, like this:

As you can see, the effect is pretty artistic; you get a sharp subject but a blurry background. Neat, right? Because a blurry background helps the subject to stand out, this is an effect you’ll often see in portrait photography.

As for aperture, the wider the aperture (and the smaller the f-number!), the shallower the depth of field.

So an image with an f/2.8 aperture will have very little in focus:

And an image with an f/16 aperture will have all of the scene in focus:

Got it? If you’re still struggling to understand – and if you are, don’t be embarrassed! – let me illustrate using two pictures I took in my garden:

The first picture was taken with an aperture of f/22, while the second picture was shot at f/2.8. The difference is obvious, right? The f/22 picture has both the flower and the bud in focus and you’re able to make out the fence and leaves in the background. Whereas the f/2.8 shot has the left flower in focus, but the right flower is less in focus and the background is completely blurry.

That’s all thanks to aperture, which controls the depth of field.

4 simple aperture examples

Here are a handful of additional aperture examples to help you wrap your head around its effects – in particular, how aperture affects the depth of field.

First, take a look at this landscape shot. It was captured with a narrow aperture, which resulted in a deep depth of field and sharpness throughout:

Now take a look at this street photo, which was taken with a wide aperture; it has a shallow depth of field:

And here’s a third example, which has a midrange depth of field. The entire photo isn’t sharp, but the main subject plus some of the surrounding area look crisp:

Finally, here’s one more example with an ultra-wide aperture for an ultra-shallow depth of field:

What’s important to know is that the aperture offers you creative control as a photographer. Want to create a blurry background? Pick a wide aperture. Want to keep your shot sharp throughout? Pick a narrow aperture.

Of course, you also have to remember the effect of aperture on exposure, which is what makes things a bit more complex (but a lot more fun!).

Adjusting the aperture on your camera

Now that you’ve made it this far, you might be wondering:

How can you actually change the aperture on your camera? What do you have to do?

Fortunately, adjusting the aperture is easy. You just set your camera’s shooting mode to Manual or Aperture Priority. Then rotate the relevant camera dial to change the f-number. (The specific dial will depend on your camera model; if you’re struggling, consult your manual.)

Which aperture is best?

When photographers first learn about aperture, this is a question that crops up constantly.

But as you’ve hopefully gleaned from the sections above, there is no single best aperture that you can use all the time. Sometimes you’ll want a deep depth of field or you’ll want to darken down a too-bright shot, in which case you’ll need to use a narrow aperture. Other times you’ll want a shallow depth of field or you’ll want to brighten up a too-dark shot, in which case you’ll need to use a wide aperture.

That said…

There are apertures that get used consistently in certain genres. I’ll cover them briefly below, starting with:

The best landscape photography aperture

Landscape photographers gravitate toward small aperture settings, such as f/8, f/11, and even f/16.

Why?

When you’re shooting a sweeping photo of the land, sea, or sky, you often want to keep the whole shot sharp. That way, the viewer can appreciate every little detail of your majestic scene.

Plus, a deep depth of field makes the shot feel more real, like the viewer could physically step into the scene.

The best portrait photography aperture

In portrait photography, it can be handy to have your subject perfectly in focus but the background nice and blurry. That way, your main subject stands out and the background doesn’t become a distraction.

In other words, use a large aperture to ensure a shallow depth of field.

It’s a trick used by family portrait photographers, headshot photographers, fashion photographers, and more.

The best macro photography aperture

Macro (i.e., close-up) photographers tend to disagree over aperture.

Some macro photographers use a very narrow aperture because depth of field gets shallower at high magnifications. And by using a narrow aperture, a macro photographer can ensure that their entire subject is in focus, even if the background is blurred.

Whereas other macro photographers embrace a shallow depth of field. They use a very wide aperture for a soft-focus effect.

Which is the way to go? That depends on your preferences! Both approaches work well, and there are plenty of professionals using each technique, so don’t stress about it too much.

Aperture in photography: final words

Hopefully, you now have a good understanding of aperture in photography and how you can use it to gain creative control over your photos.

But if you’re still a little confused, that’s okay. Grab your camera and do some experimenting. Find a subject – an apple works great! – and shoot it with different apertures. Watch as the depth of field changes.

Pretty soon, it’ll click. And your photos will (genuinely!) never be the same again.

The post Aperture in Photography: A Beginner’s Guide (+ Examples) appeared first on Digital Photography School. It was authored by Darren Rowse.

You must be logged in to post a comment.