Have you learned everything your new camera can do yet? If not, then you’ve found the right article.

Have you learned everything your new camera can do yet? If not, then you’ve found the right article.

I present you with five quick exercises you can try right now, to help you better understand your new camera, and how it captures light. I’ll give you some hints about what is happening, but you will need to come to your own conclusions.

If you get stuck after running the experiment, there are answers at the bottom of the article. Don’t cheat! You have to try to come to the conclusion yourself first, you will learn more if you can do that.

To do these exercises your camera will need to have a shutter (although mirrorless cameras will work here), variable aperture, and adjustable ISO. It will also be helpful if you have a Program Mode, Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority, and Manual Mode. Check your user manual to see if these exist on your new camera.

1. Play with depth of field using the aperture

You might have learned a little about your camera’s aperture in this DPS article: Seeing in Depth of Field: A Simple Understanding of Aperture. If not, take a quick look.

This first exercise is easy. I want you to line up three objects on a table in front of your camera. Make sure the objects are something easy to focus upon (have lots of lines or contrast). If you need to, borrow toys from your kids, I find those work best.

During this exercise your camera will not move, so set it on the table in one spot. Place your first object directly in front of the camera, about two feet (0.6 meters) away. Your second object should be one foot (0.3 meters) beyond the first, and the third object, another foot beyond the second. It should look something like this:

The objects should be staggered sideways to ensure they are all visible from the camera angle.

Set your camera to Aperture Priority mode. You may need to reference your camera’s user manual to find the setting. Usually it is the A or Av label on your camera’s main dial. Then set your ISO to Auto, and your focus dot to the camera’s central focus point. Again, you may need to reference the manual as all cameras are a different in how they choose focus points.

Point your camera at the first object (so the active focus point is on it), so that your camera focuses there. Set your aperture to the smallest f-number your lens can achieve; it will around f/1.8 or f/3.5. If you are using a zoom lens, pick a focal length somewhere in the 40-60mm range.

Now take a picture. Without moving your camera, change the aperture to f/8. Take another picture. Then change your aperture to the largest number (smallest opening) your lens can achieve; this might be f/22 or even higher. Take a third picture.

Next, point your focus point at the second object, so it is sharp, and repeat the steps above so you have three new images at a low number aperture (f/3.5), a medium number (f/8), and a high number (f/22).

Lastly, focus on the third object and repeat the steps again.

You should now have nine images; three of each of the objects in sharp focus, at three different apertures.

The aperture on your camera controls the depth of field. What do you notice as the aperture number (or f-number) gets larger? Are more or less things in focus? What about when you focus on an object further away and look at the same aperture setting as a close object? Is more or less in focus?

BONUS EXPERIMENT: Run this experiment again and set your focal length to a smaller number (wide angle view) such as 18mm. What differences do you notice now?

2. Exposure compensation when the exposure is wrong

This may be disappointing to find out, now that you have a fancy new camera; but your camera is often wrong with its automatic settings. I’m sorry, but it just is. It’s not human and it has limits, but you can get around them.

This may be disappointing to find out, now that you have a fancy new camera; but your camera is often wrong with its automatic settings. I’m sorry, but it just is. It’s not human and it has limits, but you can get around them.

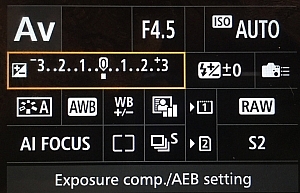

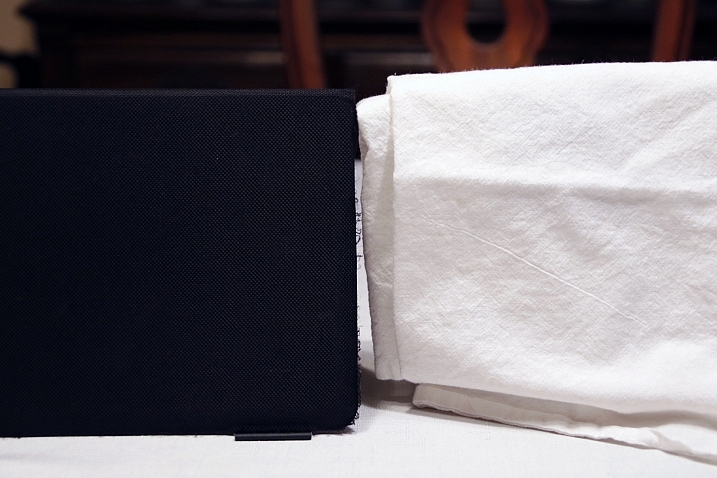

Choose two objects for this experiment. One should be predominantly white, and the other should be predominantly black. Set them side by side. I chose a black iPad cover and a dish towel in this case.

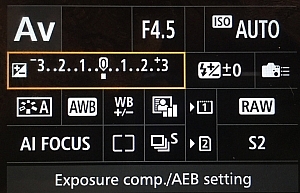

Set your camera to Aperture Priority and choose the lowest f-number you can (e.g. f/1.8 or f/3.5). Set your ISO to 400 and turn autofocus on. Reference your user guide to set your camera’s metering to Spot or Center Weighted. This is typically signified by a small circle in the middle of the viewing area.

Set up your camera in one position so it doesn’t move much, and point that center metering spot at the black object, so it fills the entire metering area. If you are using Center Weighted metering, fill as much of the center area with the black object. Take a photo.

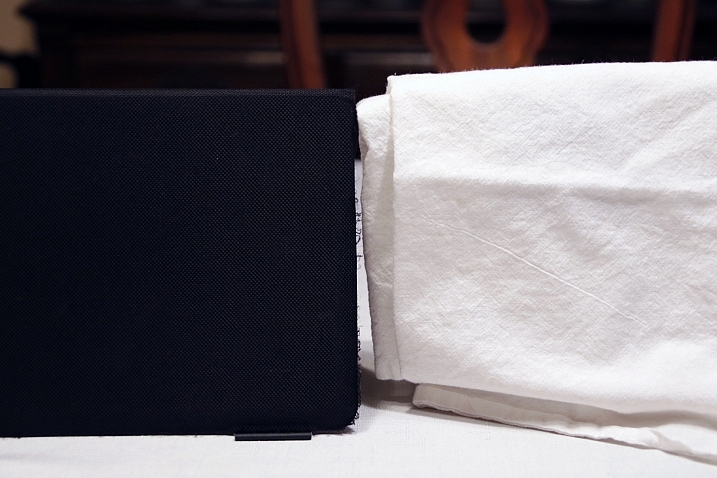

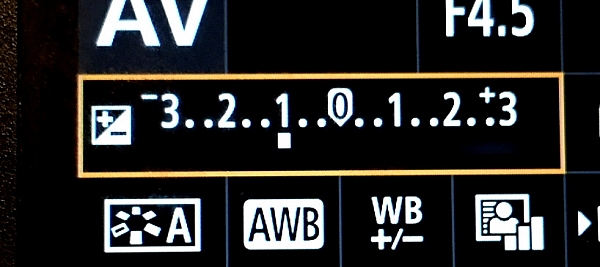

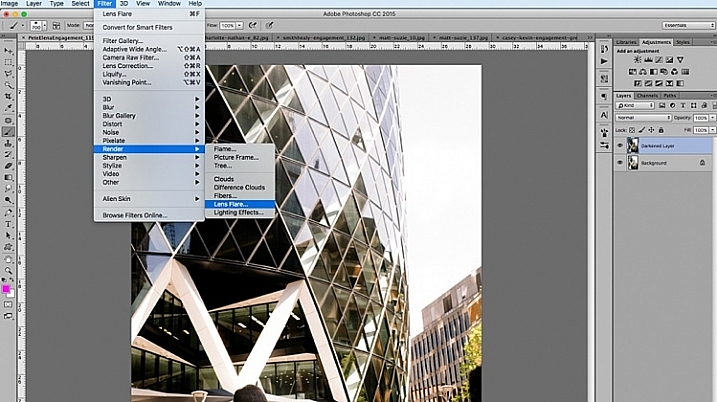

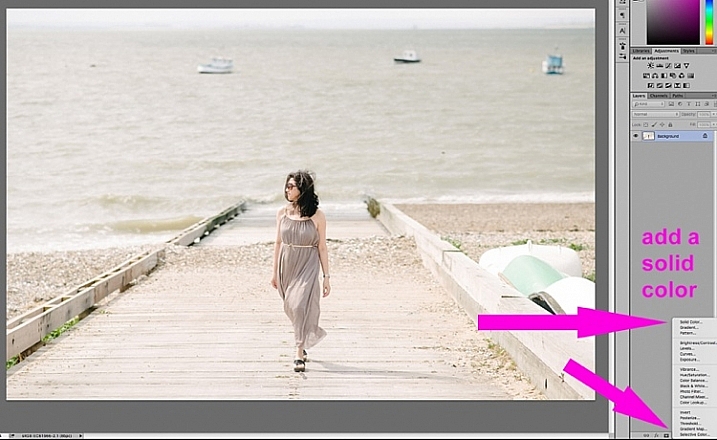

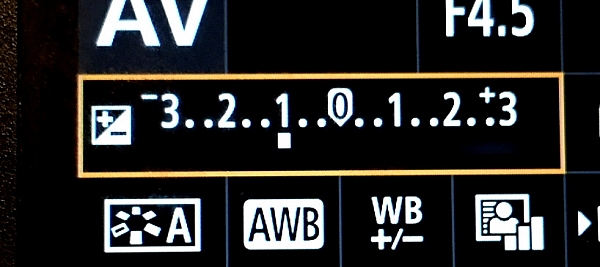

Now find the exposure bias (or exposure compensation) feature on your camera. It will look something like this:

Now find the exposure bias (or exposure compensation) feature on your camera. It will look something like this:

Change the exposure bias/compensation so it is set to underexpose by one stop. This will either look like “-1” or on some cameras there will be a scale with tick marks and one should be labeled “-1”. Move to that point. Take another identical photo of your black object.

Reset your exposure bias to zero (0) and point your camera over to the white object, so that it fills the metering area; take a photo. Then change the exposure bias/compensation to “+1”.

You now have four images. Looking at the two shots of the black object, which one makes the object look more like its actual color? What about the white object?

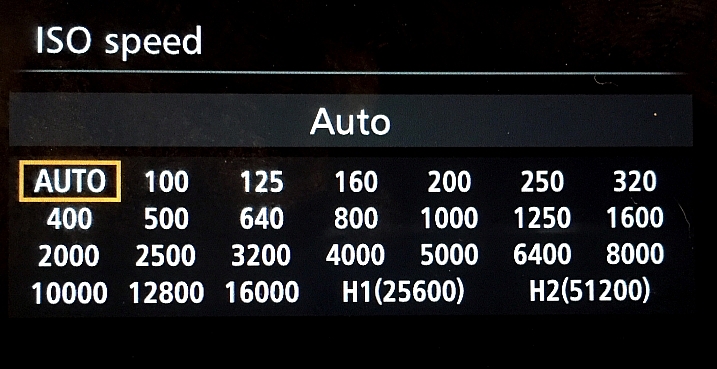

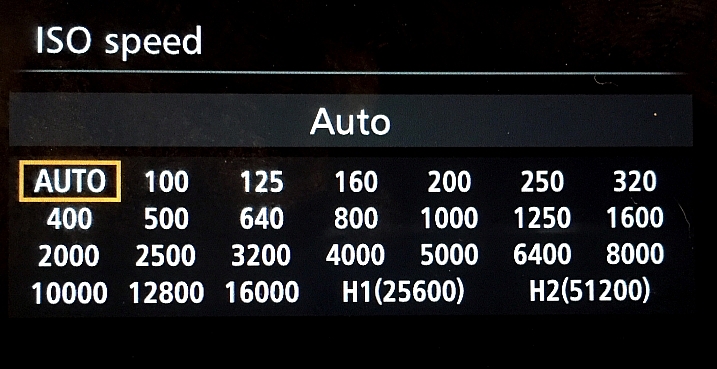

3. Test your ISO

Modern cameras have an awesome range of ISO settings, but they still have their limits. Don’t get fooled into thinking you can just shoot at ISO 6,400 in a dark room and things will be peachy. This experiment is set to help you understand what happens when you change ISO, and what your personal limits might be for your camera.

Set up a few objects on a table, at one end, and set your camera at the other end. Zoom in so the viewfinder is mostly filled with the scene in front of you. Include white and black objects, and some other colors. Have a couple of lights on in the room so it is normally lit, make sure the camera’s flash does not fire for this exercise.

Set your camera to Aperture Priority and your aperture to f/5.6. Set your ISO at 100 and take a photo. Without moving your camera much, change to ISO 200 and take another photo. Then ISO 400, take photo, ISO 800, take another shot, and so on (doubling the ISO each time) until you run out of ISO settings.

Examine the images, preferably on a computer screen, or use the zoom feature when reviewing images on your camera. You want to zoom in on the darker areas.

What do you see happening from low ISO settings to the higher ones? Do you notice a big difference between white areas as compared to black areas?

If you need a hint about what is happening read: 6 Tips for Using ISO Effectively With Your Camera.

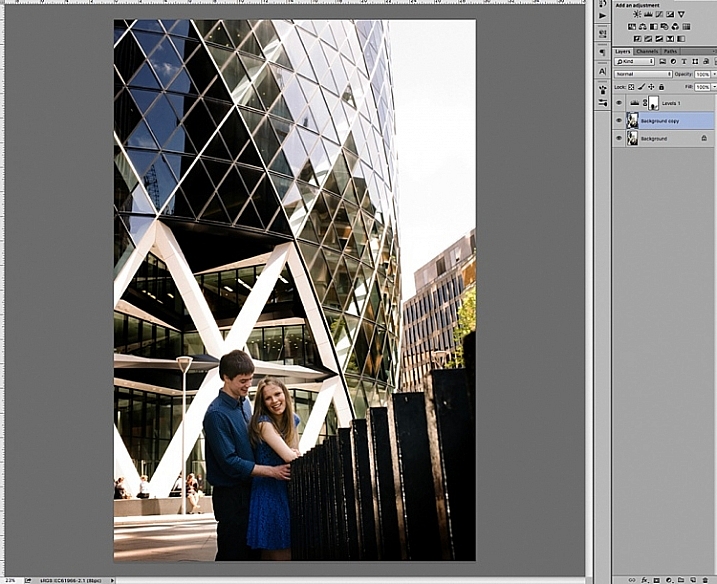

4. Add some blur with a slow shutter speed

This one is easy and quick. You may need a willing assistant, or you can find cars moving on a city street. You will want objects moving past your field of view, from side to side (not front to back) at a fairly consistent speed.

Set your camera on a solid object; this can be a tripod, desk, the hood of a car, etc. Point your camera toward the moving objects. Set your camera to Shutter Priority (S or Tv) Mode, ISO should be 100, and set your shutter speed to 1/500th.

Take a photo of the objects passing in front of your camera. Change your shutter speed to 1/60th and take another photo as the objects move.

Lastly, set your shutter speed to 1/10th and take another photo. What do you notice happened in the three photos?

BONUS EXPERIMENT: What happens when you keep the slow shutter speed of 1/10th and move with the subject while you shoot?

5. White Balance is important for good color

White Balance is very important if you shoot in a file format other than RAW, such as JPEG. Your camera will usually do a good job of guessing the correct White Balance settings, but it is important to know how to control your camera if it messes up.

You will need a place with three different light sources to make this one work. It’s okay if they are not in the same spot, you can walk around. You will also need a piece of white paper with writing on it, to help focus.

Set your camera on Program Mode. This allows your camera to handle shutter speed, ISO and Aperture automatically, but you are going to take control of the White Balance. Again, you may need to reference your camera’s manual as each manufacturer handles these changes differently.

First, find a scene that is lit by daylight. Set your camera’s white balance to the Daylight Preset. It’s setting looks like a little sun in the image above. Take a photo of your white paper with the daylight hitting it. If you can only manage cloudy daylight, that will be okay as well.

Without moving much, set your White Balance to incandescent or tungsten (looks like a little lightbulb). Take the exact same photo you did before. Lastly, set your White Balance to shade (a little house icon with shade next to it). Take the exact same photo.

Which White Balance preset under daylight conditions produces this color?

Next, move to an area lit by incandescent or fluorescent light. This would also include compact fluorescent bulbs. You can hold your paper close to the light source for these next photos, just make sure the light is falling on the page and not coming through it.

Run through the same three White Balance settings as before; daylight, incandescent and shade.

Which White Balance preset under incandescent lighting produces this color?

What happens to the color of the white paper when each of these changes are made? Its color changes, doesn’t it? When you shot with the shade setting, did things get more blue or more yellow? Think about how you can use this in your photography once you understand how it works.

Answers and Helpful Hints

Now that you have played around a little, let me help clarify what you should have seen in each exercise.

1. In the first exercise you should see more depth of field (more things in focus, front to back) as the aperture number increases. As you focus further away from the camera, the depth of field also increases at the same aperture. This might be hard to see in this limited of a test, but it is explained better here: How to Control Aperture and Create Images You Love.

2. Your camera is set to expose the world as if it were 18% gray. This means objects that are black are exposed to make them more gray; the same goes for white things. If you are taking pictures of something already gray, like pavement, then there is no adjustment needed. Otherwise, to make white things white, you need to tell your camera to overexpose (that was the “+1”) and to make black things black, you need to under expose (“-1”). More info on exposure compensation is available here: Using Exposure Bias To Improve Picture Detail.

3. As ISO increases, digital noise (not the same as grain in the days of film, but similar) increases. Noise is usually not desired but as time goes on, camera manufacturers get better at reducing it. That’s why camera owners five years ago were told not to go over ISO 800, or there would be too much noise. Now, I regularly shoot at ISO 2000 with results that work for me. It’s important to know the limits of your camera so you are okay with exceeding them in certain circumstances.

4. As your shutter speed gets slower, the chance for blur increases. This can be blur from you moving the camera (we have all done this before) or from your subject moving. Blur is not an inherently bad thing, it can be used with great affect. But it’s important to know when, and how much, works best for you. Play around on this one a little with different subject speeds and shutter speeds.

5. White Balance can be trickiest when there is more than one light source and it’s helpful to know which way to adjust the colors. A lower temperature (incandescent and fluorescent) give more of a yellow/green cast while cloudy and shady gives your more of a blue tone. If you want to eliminate that color cast in your images, move the White Balance toward those settings.

The great thing about photography is it is highly reproducible. When you do this, that happens – and when you do this again, that happens again. That makes it a great art form, in which experimenting can teach volumes, if you keep control of the variables. You might note that only one variable was allowed to change in each of these exercises, that was on purpose.

Go forth and experiment more with your new camera. The more you shoot and the more you experience through the lens of your camera, the more you will learn!

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

tablet_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_tab-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78623” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

googletag.cmd.push(function() {

mobile_slots.push( googletag.defineSlot( “/1005424/_dPSv4_mob-all-article-bottom_(300×250)”, [300, 250], “pb-ad-78158” ).addService( googletag.pubads() ) ); } );

The post Do These 5 Quick Exercises to Learn What Your New Camera Can Do by Peter West Carey appeared first on Digital Photography School.

Digital Photography School

Have you learned everything your new camera can do yet? If not, then you’ve found the right article.

Have you learned everything your new camera can do yet? If not, then you’ve found the right article.

This may be disappointing to find out, now that you have a fancy new camera; but your camera is often wrong with its automatic settings. I’m sorry, but it just is. It’s not human and it has limits, but you can get around them.

This may be disappointing to find out, now that you have a fancy new camera; but your camera is often wrong with its automatic settings. I’m sorry, but it just is. It’s not human and it has limits, but you can get around them.

Now find the exposure bias (or exposure compensation) feature on your camera. It will look something like this:

Now find the exposure bias (or exposure compensation) feature on your camera. It will look something like this:

You must be logged in to post a comment.