|

|

Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki films actor Forrest Goodluck in The Revenant, for which he won the 2016 Academy Award for Best Cinematography. Lubezki shot The Revenant entirely with natural light.

Photo: Kimberly French

|

On February 28 Emmanuel Lubezki won his third consecutive Oscar for Best Cinematography for The Revenant, starring Leonardo DiCaprio. That’s an impressive feat, but even more so when you consider that he also took home the Oscar in the same category in 2015 (for Birdman) and in 2014 (for Gravity), and has been nominated a total of eight times, making him the first cinematographer to win three Academy Awards in a row and establishing his place as one of the preeminent cinematographers of our day.

Lubezki is known for creating immersive, organic experiences that draw viewers into the story, often embracing wide angle lenses and long continuous shots to achieve this effect. His work has variously led audiences through sensory experiences that have evoked strong emotion, a sense of exploration and freedom, magic, beauty, authenticity and, at times, even discomfort. Many will remember the twelve-minute opening scene in Gravity as well as the famous (and rather tense) uninterrupted four-minute car chase in Children of Men.

A few days before the Oscars, Lubezki, who also happens to be an enthusiastic photographer, joined DPReview editors Dale Baskin and Rishi Sanyal to share his thoughts on a variety of topics ranging from artistic to technical. Of particular interest to DPReview readers, he discusses the impact of digital technology on filmmaking, how he selects and tests his gear, and why he chose to shoot The Revenant entirely on digital cameras using only natural light. Additionally, he explains his excitement about InVisage QuantumFilm, a technology we’ve covered before, and why it excited him enough that in November of 2015 he joined InVisage’s Advisory Board to provide expert and artistic insight to help guide the company.

After our 2-page interview, be sure to visit page 3 for our Editor’s Note that dives deep into some of the technical ground covered. And to get a more personal view of Lubezki’s work you can follow him on Instagram @chivexp.

DPReview: Hi, Emmanuel. Thanks for taking some time to meet with us. Everyone here at DPReview is really excited about the chance to talk with you!

Emmanuel Lubezki: Sure! I know DPReview. Every time I’m going to buy a camera I check you guys out! I’m a photographer and I’ve been shooting movies for close to thirty years. I love shooting movies and taking still photos.

DPR: You’re an inspiration to many of us because of your artistic vision and your use of technology to achieve it. How do you choose the technology you use for your projects?

EL: You know, one thing I can tell you is that I’m the worst geek in the world! Sometimes I don’t even know how to turn on the camera. [Laughs, obviously joking] But from an instinctive, craftsman point of view, whenever I’m going to start a movie or buy a camera or start a project, I do a lot of tests. All these test help inform me of how I want to shoot the movie, which equipment I’m going to use, how I’m going to mix equipment and so on. Like how my Nikon D810 works. After testing it and comparing it to other cameras I know what that camera can do for me as opposed to other cameras.

DPR: You definitely picked the right camera with the D810. It has the most dynamic range of any camera we’ve tested.

EL: That’s exactly why I picked it. One of the most important characteristics for any equipment that I’m going to use is how well it can capture high dynamic range. I’m an old cinematographer, so I was used to the high dynamic range of film. If you consider the high dynamic range of Kodak [negative] film, especially in the latest years, to be like the 88 keys of a piano, that was what I needed to go out and capture the highlights, the sky, the shadows in the subject’s hair, and so on.

Then suddenly film started to collapse and disappear. It happened too early and it happened too fast. It was a result of the studios and the exhibitors going into digital exhibition, so suddenly there was no business for printing. That was the biggest businesses for the labs, so the labs started to close down. It became very hard to shoot film.

Unfortunately, the transition happened too early and the cameras weren’t ready. The digital cameras that came out in the beginning (around 15 years ago) were not even close to the high dynamic range of film. I worked with a few directors, including Michael Mann, to do tests with digital video imaging. For certain things, we liked and used it, but it was primitive and it wasn’t ready to take over and become the main technology for capturing images.

I think now we’re in a very good place where the digital cameras are allowing us to do many things we couldn’t do with film. But it’s still the dynamic range – the high dynamic range – where digital cameras, as amazing as they are at capturing shadows and not having any noise, don’t allow you to capture those 88 keys of the piano I was used to. And movies get hurt by that.

For example, the last movie I did [we were shooting] in the forest, and when looking at the sky I wasn’t able to capture the little round ball of the sun and also capture the face of the actor. It’s stressful for a cinematographer. So the idea of new sensor technology, like what InVisage has demonstrated in their QuantumFilm technology, that will allow us to go back to 88 keys of dynamic range or more is incredibly exciting.

|

|

Shooting The Revenant in all natural light pushed the limits of dynamic range on the digital cameras used for the production.

Photo: Kimberly French

|

DPR: You’ve worked with InVisage, the company behind QuantumFilm, and seem very enthusiastic about what that technology can do for filmmakers and photographers. Why?

When InVisage approached me and showed me their sensor technology I got very, very excited. As people would say, it’s music to my ears. Actually, it’s music to my eyes what they are doing! What they’re attempting to do is everything I’ve been looking for, and that’s why I’m so excited to work with them.

The first thing I’m excited about is the high dynamic range of QuantumFilm, but the other thing that’s important is a camera that has a global shutter as opposed to a rolling shutter. That’s something that we suffered with a bit during Gravity. When you’re doing a lot of digital effects and stitching things together, not having global shutter can become a big issue, as you guys know.

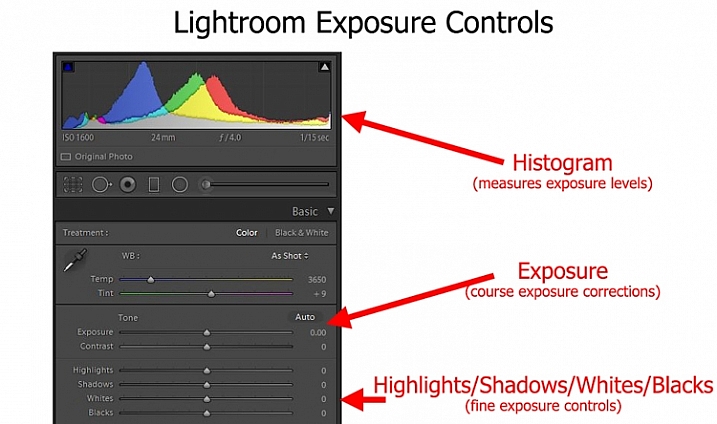

DPR: You’ve mentioned the incredible dynamic range we’re starting to see with technologies like QuantumFilm and from cameras like the Nikon D810. How does digital fit into your workflow now? And have you found that you need to have a different method and philosophy for exposure when shooting with digital as compared to film?

EL: Absolutely. Very different. When I signed on to do The Revenant, I wanted to do all the day scenes on film, just because of the high dynamic range, and I wanted to do all the dusk and night scenes with a digital camera. That’s because the digital cameras are more sensitive to light. They can see more in the shadows, and you can push them a bit. For example, let’s say that Arri says their camera is ISO 800 native. You can shoot it at IS0 1600 and there’s still no noise. You’re able to shoot scenes at night with firelight, and you can capture the stars and the Aurora Borealis in the night sky – things that film couldn’t do.

I started doing a lot of tests while we were rehearsing the movie, and every time I went back to the lab to see the results, the images I was capturing with the digital cameras were more interesting to me because they had less noise or no noise at all. It was like opening a window for the audience to get them immersed in this world, whereas film still had that poetic or romantic look, and the grain and texture was making the world of The Revenant look more romanticized. It wasn’t really allowing me to get immersed into the world of these trappers the way the digital cameras did.

Little by little I realized that I didn’t want to shoot the movie on film. For a middle-aged cinematographer who’s been shooting for so many years – that’s a very hard call. It’s like suddenly saying to a musician “You know, forget about your incredible piano, you’re going to play this concert with a Minimoog.” It’s heart-breaking, but the images spoke for themselves. We sent all the film cameras and film back to Los Angeles and started shooting the rest of the tests with the digital cameras. What I learned really fast is that, as opposed to film, you expose differently. You can overexpose film, and for many years I overexposed film because I liked the way you could still see the highlights, and by overexposing I was able to bring up a little bit of information in the shadows.

DPR: Because the film rolls off in the highlights, you can give it that extra light?

EL: Yes, exactly, which would then give you a little bit of extra latitude in the shadows. You would add a little noise by doing this, or grain in the highlights, but it was just a little bit and it allowed me to capture the whole ’88 keys’ [of the piano].

DPR: With digital it’s a very different philosophy, right? Because digital clips highlights abruptly as a result of being a largely a linear capture medium, and there isn’t that roll off.

EL: Yes, it’s very different. You have to underexpose.

DPR: One of the things we discuss on our site a lot is that with digital you need to expose for the highlights and brighten the shadows afterward because they’re so clean.

EL: That’s exactly what you find when you start to test. And that testing tells you how much you can underexpose before you start to lose the shadows.

Unfortunately, as I was telling you before, we’re at a moment where the cameras and the chips are just not ready enough. Let’s say they are ready, but they don’t have the high dynamic range that we would like to have. This was a very good movie to do this test because I wasn’t using extra light or artificial light, so I sometimes had to make a call and say “OK, do I lose Leo’s face or detail in his hair? Or do I lose a cloud that is front-lit and many, many stops brighter than what this camera could capture?”

So what I would do much of the time is go for Leo’s face, because he’s the star of the movie, and then I would do a second pass and capture the sky, hoping that later I could replace the sky in the scene. But obviously that’s very expensive and you can’t do it over and over. The camera is handheld and it’s moving, so tracking it [in post to overlay the two exposures] would become very hard. In still photography I do that a lot. You know, you take a portrait of somebody and if the background is way too overexposed you shoot a couple more shots.

|

|

Before filming The Revenant Lubezki did extensive tests with his cameras in order to understand the dynamic range they were capable of handling and taking advantage of clean shadow detail to expose for the highlights.

Photo: Kimberly French

|

DPR: Of course, when you underexpose, the shadows in the image become really dark in the the electronic viewfinder or LCD screen. Have you found Log gamma modes help you with digital capture as you underexpose?

EL: Yes. Not in still photography, but what I do when shooting cinema is I create lookup tables [LUTs] that allow me to see how much information I still have in the shadows if I’m underexposed. They’re very easy to create if you shoot tests and then make 2D or 3D LUTs in order to see the shadows. I haven’t been able to do it in still photography because I would probably need to get into the camera and mess with the monitor.

DPR: Would it be a bit like your D810 when using the ‘Flat’ Picture Control that raises the shadows and rolls off the highlights?

EL: Exactly. That gives you a little bit of an impression, but I’ve had a couple of hiccups where I think I still have enough detail, and then you open up the images in Photoshop and the shadows in the hair are already so underexposed that you don’t see detail. I take photos more like a hobbyist than a great professional that has an assistant with a laptop. I just have my camera and shoot.

DPR: It’s very interesting to hear all of this from someone who many people know as ‘a film guy’.

EL: I was the ‘film guy’. What I gained by shooting digital makes me much happier. That’s why I sent the film cameras back to Los Angeles. The digital cameras were giving me something I could never have done on film – because of the sensitivity, because of the immediacy, and because Alejandro [Director Alejandro Iñárritu] was able to watch everything on large monitors. Sometimes when you have 400 extras you want to watch a playback and see what all those extras are doing and things like that. Things that film doesn’t give us.

On The Revenant I was shooting at high latitudes – we were in Canada, north of Calgary, in the winter. Shooting in that part of the world, the sun is very low to the horizon and goes behind the mountains very early. By shooting with digital cameras I was able to add one or two hours of shooting to our very short days. That’s a lot of extra time for a big production. It’s millions of dollars that you don’t lose by not being able to shoot. It was also during the time of day that’s very mysterious and magical [the ‘golden’ or ‘magic’ hour], and by having the digital cameras I was able to capture things I couldn’t do on film.

DPR: Hearing you say that you’re mostly experiencing advantages when shooting digital is compelling. Where does film fit into the picture at this point?

EL: I’m not trying to tell young filmmakers or any director to not shoot film. The ideal world would be a world where we have all these different tools – where you have film, where you have QuantumFilm sensors, where you have tiny digital cameras that have very little latitude – where you have all these paintbrushes that allow you to communicate and allow you to express different things.

It will be very sad to see film go away because we have 100+ years of film history and it would be a big loss if we couldn’t print these movies anymore. You know, movies like Carol, or a movie like the Coen Brothers movie that just came out that is an homage to filmmaking – it was a good call by the filmmakers to make these movies on film. So it would be great to still have film, and it’s fantastic to be able to combine things. But in general, I feel much more comfortable shooting digital.

|

|

At the start of production, Lubezki planned to shoot daylight scenes on film due to its high dynamic range, but after extensive testing sent all the film and film cameras back to Los Angeles and shot entirely on digital.

“It was like opening a window for the audience to get them immersed in this world, whereas film still had that poetic or romantic look… It wasn’t really allowing me to get immersed into the world of these trappers the way the digital cameras did.”

Photo: Kimberly French

|

DPR: Is that comfort partly because you’ve had this realization that the formats need to be exposed differently, using underexposure on digital and tone-mapping the footage later?

EL: Absolutely!

DPR: Does everyone else in the industry understand that?

EL: I think so. I think in general professional cinematographers working in the industry know that, and if not you learn it very fast. The first day of testing you realize that you’re gaining a lot information by doing that.

DPR: Many stills photographers may not appreciate the different approaches to exposing digital and film, but you guys are doing your own tests so it makes sense that you can take advantage of the formats by using them optimally.

EL: Right now we’re talking about professionals. But imagine – hopefully in the short future – if we had QuantumFilm in our phones, what amazing things we could do with them. How many millions or billions of photographs do we see everyday where the skies are clipped? Sometimes it doesn’t matter, but a lot of times it does because you’re losing a great amount of information about the environment or the highlights in somebody’s face.

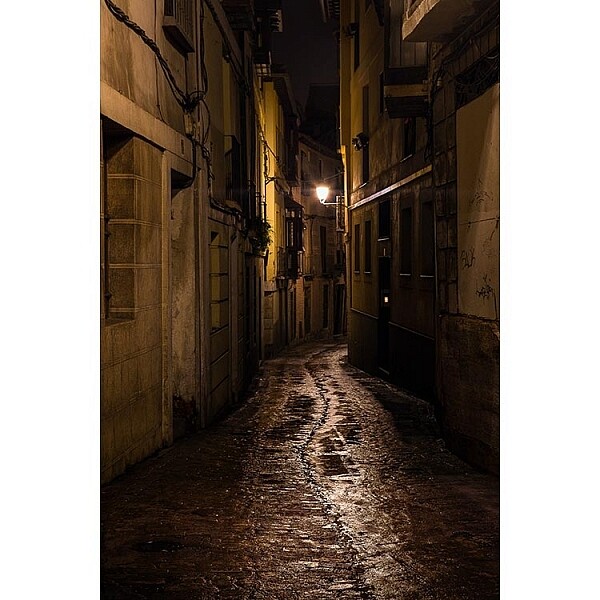

DPR: One of the first things that struck us while watching The Revenant was the realism of the image – not only due to the lack of noise, but also because you can see everything from the blues in the sky, to the warm tones in your flares and sunstars, while still clearly seeing the subject’s face naturally, not artificially, lit. And the subject’s face isn’t noisy or a plugged shadow. It made for compelling imagery.

EL: I’m very happy to hear that because it’s something that I really wanted to show to the audience! Although you’re specialists and are able to see it like that, I think even people that don’t see it the way you’re seeing it… their subconscious is telling them “This is different,” and that it’s not artificially lit [to work around the capture medium’s limitations], and that it’s the real thing.

|

|

Using digital cameras allowed Lubezki, shooting in extreme northern latitudes in the winter, to add an hour or two of filming each day during the magic hours when the sun was low to the horizon.

Photo: Kimberly French

|

DPR: Is that why you choose to do long takes and wide angle perspectives? To enhance the realism and create an immersive experience?

EL: Yes. It’s exactly those two things. We wanted the movie to be as naturalistic and immersive as possible. The long takes, the digital equipment, and the way it was exposed… all these things together worked really well.

DPR: All this technical discussion brings up an interesting question. In the digital age does a cinematographer need to be as much of an expert on the science and technology of their imaging equipment as they are an artist in order to achieve their vision?

EL: I think you have to know a little bit about your equipment, at least in the way I do, in an intuitive way. You need to be able to test it and you need to know what you can do with it. I don’t know if you necessarily need to know that the chip is connected with 27 cables into… I don’t know if that’s imperative. I wish I could learn it. I haven’t had the time and the passion to open up a camera and go through exactly how it works, but I didn’t do that on film either. To me the results were more important. What was I getting and how was it connected to the story and mood, and what I was trying to tell the audience?

Continue reading Part II of our interview with Emmanuel Lubezki

Read our Editor’s Note (Page 3)

Articles: Digital Photography Review (dpreview.com)

You must be logged in to post a comment.